Sarah-Jane Dobner considers route naming and claiming and the potential gendered and colonial implications that go with it...

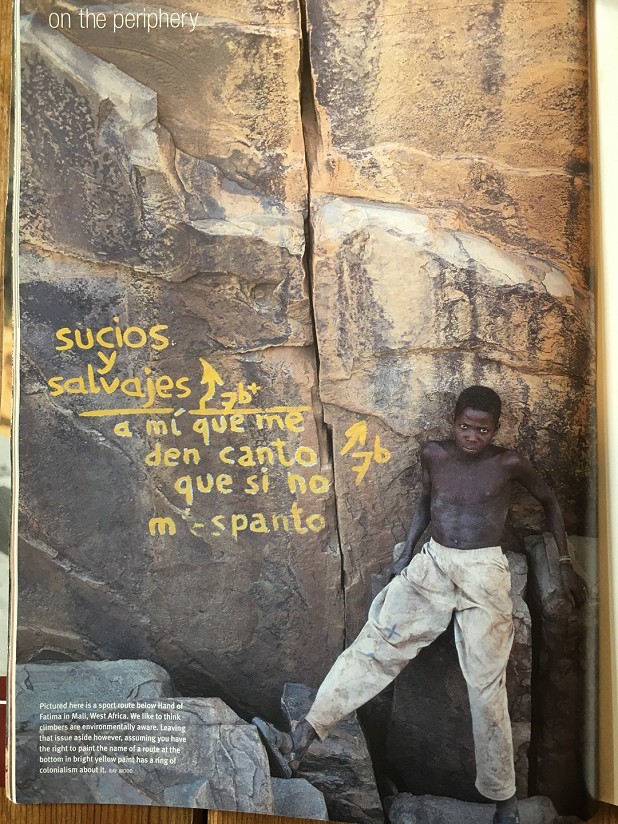

The stack of vintage magazines beside the circuit boards is always worth a browse. So much has changed! So little has changed! The outfits. The destinations, always looking wonderful, over the years. Flicking through. Eyes caught by a full page photo. Mali, West Africa. Black-skinned youth in dirty trousers leaning against the sandstone. Dwarfed by spray-painted European route names. There is a short caption, by Ray Wood. It concludes "Leaving [the environmental] issue aside however, assuming you have the right to paint the name of a route at the bottom in bright yellow paint has a ring of colonialism about it." The date of the magazine is November 2003. Nearly twenty years ago. In those two decades, how much has the conversation moved on?

There are complex issues connected to new routeing. Who gets to do what, and where? How powerful is a name? What has been the impact of the current system? What could be better? In 2019 there is much greater awareness of sexism, racism, cultural imperialism and so on. How should we integrate this knowledge into climbing, into new routeing? On the other hand, one of the beauties of climbing, to my mind, is its lawlessness. It is quite unregulated. We go where we like, put our lives in danger, clamber about rock faces all over the place willy-nilly. It's great. I baulk at imposing restrictions or codes of practice. But maybe we should?

It's a tricky conversation. The trouble is, there is no one, simple, correct answer. We're all looking for the Perfect Line. But that line can be smudged, chalked, rubbed out and redrawn depending on myriad factors including personality, gender, location, faith and time. In this article I'll consider culture and naming in the UK before moving on to look at new routeing abroad.

The cultural dominance of white guys

For the past 100+ years, UK tradition has decreed that whoever climbs it first, gets to name the route. They have free rein and can choose whatever name they like. This name and description then get preserved in guidebooks. This practice is not God-given, or Sacrosanct, or the Truth; it is just one way. A way which, it must be said, is fairly popular worldwide. But nonetheless it is not the only way, and it is not inevitable.

A conspicuous issue for me, regarding this naming and claiming convention, is the cultural dominance of white guys. Read the 'historical' sections of guidebooks. Over and over again I end up gazing at lists and descriptions and photos of white men. Which has repercussions. When one demographic (in this case white, male) monopolises a scene, it has the effect of homogenising the climbing environment. It inevitably excludes others, who are not white men. It sends out the message that This place is not for you. Not meaning to, but it does. So I can feel alienated and miffed. Feel the ghosts of women past, suffocated by skirts and convention, who could have been great first ascensionists but never had the chance. Feel conflicted, because admiration and envy are also in there. As I said in the introduction, this is not a straightforward debate.

Knowing the rebelliousness of traditional climbers - misfits! mass-trespassers! - how galling for such guys, how objectionable, to be associated with 'patriarchy', with white, male presumption, with the establishment. How did that happen? How did poacher turn game-keeper?! Or, more accurately, see how they co-exist - rebel, misogynist, husband, dirt-bag, lover, bully. We all wear many hats.

I also get it, that new-routers are the ones who invest their time and knowledge into putting up new lines. Can admire the pioneering spirit, discomfort, tolerance of risk, especially in ground-up trad. The vision! Appreciate the financial cost and equipment and dedication needed in developing new sports crags. Nevertheless, doesn't this sometimes slip into smash-and-grab? A sort of feeding frenzy to 'bag' all the best lines. All those stories of 'stealing' routes, bad/rushed bolting and fabricated ascents. Greed. And isn't it generated by this system? I'm not all against greed, per se. Greed is close to desire, and I'm a big fan of desire. On the other hand, gluttony and lust are both Deadly Sins. So shouldn't some care be taken, lest we go to hell?

Simply the idea of being able to claim and name pieces of rock resonates with presumption. A recent Canadian article summarises the response from one female interviewee: "Lilith said that she would never feel entitled to name […] a cliff…". But, both historically and nowadays, it seems men have felt thus entitled. And so this conquering and pioneering has gendered elements. Have men been, mainly, doing the conquering?

Well, why don't you get up and do it yourself then, Sarah-Jane, if you care so much? I hear you ask. Yes, indeed, why don't I? Well, because it's scary and loose and slow and there is too much unknown for me (talking onsight trad here). And regarding sport crags, I don't fancy the discomfort of hanging in a harness for hours, the noise of the drill, days spent with a wrecking bar when I could be out climbing…. So am I a hypocrite? Maybe. I'm just saying how I feel.

As an aside, and in the interests of full disclosure, I did put up a new route once, when I got hopelessly lost and led up a fresh line. I claimed it and named it. I was excited. Can feel the thrill now, of telling people, encouraging them to try it and grade it and corroborate - or otherwise - my assessment of stars. Finding a name that made sense in context. It was so fun. I can see exactly how it would get addictive. Even that terminology implies the need for treatment. Enough said. Moving on.

Redressing the balance?

Is this situation fixed, so nothing can be done? I'm not so sure. Like any history, these are selected facts, foregrounded facts. Presentation and editing continue to shape our experience. For example, it was a relief for me when guidebooks downplayed the history sections. Then I could just crack on with the climbing. Also, many of the old black-and-white photos do feature women - but often very little is said about them. Perhaps more effort could be made here? Beyond guidebooks, I know Hard Rock, say, featured no articles by women. But contemporary anthologies really can do better, can make an active effort to recruit material from a more diverse base. If there isn't a significant proportion from non-white-male-contributors in your selected essay book - why not? Because these people have been climbing. They will have stories.

As I said, new routeing is not for me. But happily, I do not represent "All Women." So maybe now is the time to set about purposefully widening the field, so a greater range of people put up routes? Over 25% of climbers, according to the BMC, are women now. There are many girls coming up in the sport. So shouldn't the aim be for a quarter of new routes to be female-led? For diverse new routers to have access to tools and equipment and training, to feel they can name. Should more effort and funding be directed towards such investment? This could be on every level, from individual activists passing on their knowledge to non-white-male enthusiasts, to increased support from the BMC, clubs and sponsors.

Is this pie in the sky? There is so little unclaimed rock left in Britain (more on that later), so has the horse bolted (so to speak), would this be tokenism, divvying up crumbs? Plus I realise my position is rife with contradiction. That I'm dubious about naming and claiming at all, philosophically, conflicts with my call for women and other under-represented groups to put up more routes. In addition, setting up a binary of "men" and "women" sits badly with me - it is simplified, flawed, as I see gender as more nuanced and fluid. And besides, "men" are not the enemy. These are my climbing partners, my friends. The perfect line wavering, meandering, zig-zagging. More like a scribble. A scribble of ideas.

The power of a name

What about the names themselves? Why does it matter? I appreciate we are all different, that names won't have the same impact on everyone. Personally, I am interested in language, and the symbolic (and actual) power of words. Naming is not peripheral to me, not a meaningless add-on. It gives a flavour to the whole area, to the whole route, the whole experience. In the wider cultural context, white, British men have named buildings and roads and stars and plants after themselves and each other and we all have to walk around and write addresses and orientate ourselves in the midst of this hubris. At the same time, there is a long, inglorious precedent of women, and people of colour, being written out of history, and their contributions minimised. Naming matters.

I'm not advocating chucking all the babies out in this dirty water. I'd like to celebrate what we have. Sometimes, particularly in trad, the name of the route is so good it ferments the mystique. Like countless others, I wanted to climb "Dream of White Horses" at Gogarth for many, many years before I made it to Wen Slab. Yes, I knew it was a classic - but what a name! RIP, Ed Drummond. I also adore crags where generations of new routers have riffed with the theme. So on the military range in Pembroke, amongst a regiment of others, we have Army Dreamers, Front Line (the first buttress to face the sea! hats off to that namer), Space Cadet (steep, so you would fall into space! HATS OFF!). These fill me with delight.

On the other hand, sometimes names miss the mark or are downright toxic. Names, intended to be light-hearted, edgy or funny to the namer may be offensive, grating and rude to someone else. And when that 'someone else' is of a less powerful cultural demographic (female, Black, gay, disabled) then I'd suggest it is a pretty poor name. There are plenty of slightly (or very) racist and slightly (or very) misogynist route names in Britain. I began my climbing adventures in Devon, an area not known for its racial diversity. The local crag, Chudleigh, has a route called "Wogs". I was shocked then and I'm shocked now. I can't believe it's still in the guidebooks. As to sexist names, just this week I was browsing the South Wales Sports Guide and came across "Campaign for See-through Bikinis". Not the worst, but disrespectful and laddish. This is not purely a UK phenomenon. In Kalymnos, the one easy route at the back of the wildly overhanging Grande Grotta is called, condescendingly, "Happy Girlfriend". Worse, a crag in Ontario, Canada has line after line with names like "Tampon Applicator" and "She Got Drilled". This has alienated some female climbers from climbing the routes. Start looking out for inappropriate names; they're out there. They're everywhere.

How do you imagine women and/or people of colour feel about being at these crags, climbing these routes, reading these guidebooks? Would they feel welcome, respected, part of the in-joke? An insider? Or are they being told this joke is not for them, this route is not for them, this crag is not for them, this sport is not for them? And, clearly, the linguistic landscape would be different, more various, more unexpected if more diverse people did the naming. What names are not being told, not being heard?

Aside from outright insult, another feature to look out for is a stylised, machismo in route names - "Driller King!", "Sports Wars"! Such names have so little to do with the landscape, and so much to do with assertions of masculinity. Would you want to tackle a route called, say, "Cute Fluffy Kittens" or "Glittery Nail Varnish"? They're equally silly, but they stand out as ridiculous, as we're not used to a hyper-feminised nomenclature. A little off-putting? Remember that feeling! For that is how I feel.

Other ways and other names

There could be methods other than naming-by-the-first-ascensionist. It is possible. Just because we're used to one mechanism doesn't mean it's the only way or the best way. It's just the one with which we're familiar. The current way seems peculiarly British somehow - that winner-takes-all, first-past-the-post mentality. Planting a flag. Staking ownership. As an alternative method, names could be given by local schoolchildren, by near-by residents, by poets, by vote, by online competitions. No end of possibilities!

Names could also be computer-generated. In 2018, UKC sent its Logbook database - including over 432,000 route names - to a specialised neural network (UKC article). By studying current names, the computer learnt the 'rules', and generated names of its own. Its creations act as a mirror. Reflecting the current gender bias and proclivities, 'man' and men's names were regurgitated and various crude / rude words emerged as a clear pattern. On the other hand, some names which popped out of the neural network are utterly delightful and surprising, like these for example: The Folly Cloud, No Rocks Egg, Candy Storm, Strangershine...If a more varied, balanced, nature based, movement based vocabulary was offered to the neural network, why shouldn't Artificial Intelligence have a go? Time to share!

And what might the impact of this be? If individual glory (naming and claiming) was by-passed, as well as expanding naming potential, would this alter the nature of new-routeing? Would the avid drive to grab routes soften a little? The scales tip back to desire? Perhaps there could be a naming oversight committee, made up of diverse peoples in the climbing community, 8% Asian, 4% Black, at least 50% women - in line with the UK population. Why not?

And what to do about currently offensive names? Guidebook writers make efforts from time to time: a description of "Happy Girlfriend" notes the route is also suitable for happy boyfriends; embarrassed disclaimers accompany "Wogs". Such awareness is appreciated. But can't the names themselves be changed? Re-writing history is always uncomfortable, but history is usually uncomfortable for someone (and frequently not the victor). In Sweden in 2010 certain offensive route names were retrospectively banned and altered. Is it worth re-naming grossly offensive routes? Or should we, as a community, sit with our shame?

New routeing imperialism

As Ray Wood observed in the opening paragraph, isn't there a whiff of colonialism in putting up lines abroad - a new routeing imperialism?

It's easy to see why Brits seek new lines outside the UK. There is a shortage of virgin, native rock. British climbers started tackling peaks and cracks and grooves over a century ago. Save for the odd E9 and E10, the peach lines - in England and Wales at least - are gone. These days, new routes are frequently bolted, on tiny crags and outcrops dug out from mud and ivy in forgotten backwaters, shattered quarries which used to be overlooked as hopeless but are now appreciated as grist for the mill.

So it seems that many British new-routers are putting up lines beyond these shores. Unclaimed rock! Cherries to pick! But this is also occurring in a particular context. Many of these locations are less economically privileged. We know our backstory of colonialism, imperialism, our involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, the Elgin Marbles, our taking without asking. Isn't it a little like going on safari and shooting big game? Because we've killed all our own tigers and elephants. The routes get named with English references, English in-jokes, English language. Plus routes must surely have been named and claimed by Westerners, over the years, that actually had earlier, undocumented, indigenous ascents. It makes me feel uncomfortable. How to square this relentless claiming and naming with respect for local rock, local people, the local climbing population?

The British have done plenty of inappropriate naming. Countries on other continents (Rhodesia after the white supremacist Cecil Rhodes). Mountains in other parts of the globe (Everest after British surveyor George Everest). "Everest", not surprisingly, had many names before. Tibetan, Nepali, Chinese, Indian names. Names which meant things like "Holy Mother" and "Goddess of the Sky". Do you see the change here? Whereby omnisciently-powerful feminine divinities are replaced by the name of a white man. Last year a group of local women made the first ascent of a mountain in Afghanistan. Together, they named the peak, "The Lion Daughters of Mir Samir Peak" (UKC article). Lion Daughters! It feels that could only have been named by them. Their contribution enriches the literature and the landscape.

The decolonisation of climbing

If you are climbing in an area which currently has no active, indigenous climbing scene, when is it okay for you, as a Brit, to name and claim all the key lines (and the minor lines) before that nascent climbing community has had time to develop? Imagine how you would feel if you were a local person and, having gained climbing wherewithal, you find the native rock surrounding your home purports to be labelled, route after route, by English (or French, Spanish, other European) names?

Maybe it's time to reconsider the belief, amongst Western climbers, that rock lines are always free pickings. Perhaps it could become common practice to open in-depth communications with local people before putting up new routes. What relationships do indigenous peoples have with the rocks? What issues matter to them? Clearly, this would involve additional time, resources and money. It's easy to foresee problems with language barriers, cultural misunderstandings and consultation with nomadic populations, for instance. Nonetheless, isn't it worth considering taking climbing in this type of ethical, postcolonial direction? And the greater the power imbalance, surely the more effort should be made? However, to achieve this, we would need to prioritise sensitive listening over gung-ho adventuring and route-bagging. Can we self-regulate or should there be guidelines? Or would that mire our sport in bureaucracy?

What else, specifically, might ameliorate the colonising flavour of claiming and naming routes abroad? Money is frequently cited - that climbers bring cash to deprived areas, funding which is of significant benefit to local communities. Climbing is then like any other tourism. But can we do more? There must be many options, which may or may not seem familiar or viable at present. For example, is it possible to just climb and enjoy, without naming and claiming routes? Then this can be left to others, to locals, in due course. Is it different if you live there? If you are investing, long term, via language, friendships and finance, in the place you've made your home? How about supporting the development of a local climbing community, sharing skills and kit? Or deferring on choice of route-names to indigenous peoples - why not leave marked-up topos with, say, the village elders, the school, the local women's co-operative - and ask them to name the lines? Names would then be in indigenous tongues and, translated into English, would provide insight into the locale as well as giving a sense of ownership to that community, in perpetuity.

Conclusion

If 2003 was too early, is now the right time? Time to find a more perfect line when putting up new routes and giving them names. A perfect line in the rock face. A perfect line in the guidebook. A perfect line between climbing for yourself and respecting others. Between exploration and exploitation. Between past and the present. Between what's lovely in theory but unfeasible in practice. Between doormat and collaborator and killjoy feminist. The perfect line when borders and genders and heart-body-mind are shown to be so fluid. The perfect persuasive or jarring sentence to trigger a debate.

- ARTICLE: Pembroke: Part Atoms, Part Song 21 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: A Feeling for Rock 10 Nov, 2021

- CRAG NOTES: Fairground under Wraps 1 Feb, 2021

- ARTICLE: Portland: Here be Dragons 24 Aug, 2020

- FEATURE: Costa Blanca - Book of Wonders 19 Feb, 2020

- OPINION: Cyborg-Climbers - Come to your Senses! 16 Jan, 2020

- FEATURE: The Western Isles: Checkmate 5 Dec, 2019

- ARTICLE: Gogarth - A Gala Performance 19 Aug, 2019

- FEATURE: Kalymnos: The Smooth and the Rough 15 May, 2019

- FEATURE: Poetry - Song of Bare Blåbær 21 Mar, 2019

Comments

OK. I'll kick it off and let battle commence.

My first thought was that it was a spoof but it is not really funny enough for that. A decent spoof should suck you in, enrage and then give you a sly dig in the ribs to let you know you have been had. Maybe it's just a poor spoof. Or maybe it's a troll. If not, it is easily the most muddled load of drivel I have read in a very long time (and I'm a regular here at UKC so I do see my share of drivel).

My first response was that if someone doesn't like route names and being told where the routes go there is a very simple solution: don't buy the book. You get to follow your nose and over the years save yourself quite a few quid into the bargain so more money for beer. Result. You may of course miss out on the gems, wasting your precious climbing days bumbling up stuff that is boringly easy for you or continuously failing of stuff that is all too hard hard but, hey, that's exploration, right? Meanwhile those of us who do want this kind of info can get on with enjoying ourselves.

The fact that most of the older routes were put up by 'white guys' obviously irks but it is simply a fact of history. Get over it. You can't change what happened (for whatever reason). Happily these days more women are coming to the fore. The article actually quotes Hazel Findlay, one of the most respected climbers in the world these days so, however belatedly, the times they are a-changing.

There are too many self-contradictions to go into them all and I'm sure other people will have their favourites but for me the ultimate nonsense was, having said 'one of the beauties of climbing...... is its lawlessness' we come to the suggested 'naming oversight committee'....at which point I gave up and went to make a brew before coming back to finish the read though I really don't know why I bothered.

Lots of interesting points for those who do new routing to consider in order to be more inclusive. The fact that whoever takes the time, effort and brave pills to do a hard trad new route does deserve the right to call it what they want should not be changed be they man, woman or a minority though Imo as they have earned that right.It would take a pretty egoless climber to let others name the new route for her/him (which is a wonderful new idea)so I don't know if that would catch on. Most route names if not aesthetically pleasing or witty can be plain boring descriptions of the rock or line which are also very helpful though.

As for naming first ascentions in foreign countries is it not traditional in a competitive way that spurs local climbers to do more which can be a useful driver? This has happened all over the UK by climbers from other parts stealing lines from local climbers pushing them to up their game or go and steal routes from those areas.The patriarchal history of climbing naturally reflected in some route names could be used by the inspiring new female climbers to stamp the female sex more in the guidebooks. It is mildly annoying when you see route names of easy climbs called Pram Pushers or a hard route called No Place For A Wendy etc but again that should be used to Inspire witty names created by lassies that poke fun back.

Obviously in poor countries people can't compete with us but could the names of new routes done abroad by European climbers not just be translated into the local language by the local climbers? I certainly think it is another excellent point you raise for consideration by foreign climbers naming new routes by perhaps naming it in the local language taking into consideration local historical figures, culture etc, imagine how locals would appreciate it more, similar to how people appreciate you making the effort to speak in their language.

Excellent article, really enjoyed it as it is very thought provoking and original, thanks.

On first sight of this I find myself feeling like a complete gammon. Here is a liberally minded woman with new ideas and there's me disagreeing almost completely.

I'll let it all digest before coming back with some views.

This is modern day emoti-bollocks writ large. I'll concede that spraying route names on rock is vandalism (arguably, as is bolting), and some route names are offensive, but first ascentionists don't own a route. Nothing is taken or stolen in the ascent. Locals can happily ignore the route, rename it or whatever. A route is only reified by the community that values it.

Wow, that went on a bit! (I considered writing Man, that went on a bit but thought it too easy).

I picked up on some points, namely:

The go your own way idea, climb where suits you. I am currently putting together a collection of ideas on this for my club journal. Climb where you feel your route should go. There are lots of stunning lines which incorporate bits of a number of routes. This has been known to upset people.

Naming, I long for the day I can buy an ice axe called the daisy, or some cams called butterflies. The whole macho name culture pervades much deeper than route names. Everything has to be either aggressive (rambo) or overly technical (x5. 101 cv) in its nomenclature to sell.

Historic route names. Leave them be. If we chuck them down the memory hole, how do we learn from history?