Great mountain writing doesn't have to involve great mountains. And the reverse is also true. One of the less exciting books I know is the official account of the 1953 Everest expedition. Everything went according to plan; the weather was favourable; they got to the top. And Sir John Hunt, the official leader writing the official account, didn't allow anything so un-British as anybody's emotions.

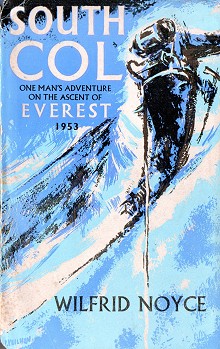

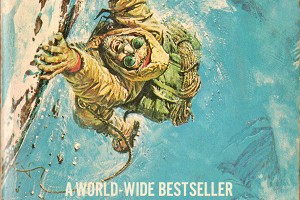

Everest is important, anyway: it is the world's highest hill, after all. And for a more insightful, as well as more entertaining, story of it all, Wilfrid Noyce, a minor poet and top climber, writes a lot better than the official account by Hunt. Published the year after the successful first ascent, his book, 'South Col: One Man's Adventure on the Ascent of Everest', even includes some poems.

This particular Wilfrid was born in 1917 into the climbing establishment, a nephew of both Colin Kirkus and Geoffrey Winthrop Young. Like most of them lot, Wilf was public school followed by Cambridge, where he was one of the photographic team on Whipplesnaith's 'Night Climbers of Cambridge':

He became one of the leading climbers of pre-war generation, and was the younger lover of Menlove Edwards, collaborating with him on the celebrated Lliwedd guidebook of 1938.

They've done it. Good. Now we can go down...

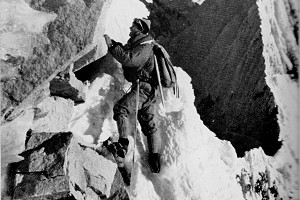

In 1937, aged 19, he contributed indirectly to early mountain rescue in the Lake District. He was climbing his Uncle Colin's route Mickledore Grooves (VS 5a) on Scafell (VS, 5a) in his socks, seconded by his lover Menlove Edwards at the other end of 90 feet of three-strand, hempen balloon cable. At the top of the main pitch the lump of sodden turf he was standing on came away, and he fell the full height of the cliff. Two strands of the balloon cable broke, bringing him to rest just above the rocks of Mickledore.

It was a hard job bringing the concussed and unconscious body down to Wasdale Head. So hard that it led to the placing of the stretcher box at the Pikes end of Mickledore, the one that's still there today.

Noyce died aged only 44, climbing Mont Garmo in the Pamirs with another notable climbing writer, Robin Smith. But before that, Everest in 1953.

Everest

The Himalayan Committee had had enough of heroic futility. They just wanted the thing climbed. And the way to do that was less inspiration and more organisation, with Col. John Hunt at the head and 350 porters and 13 tons of stores trailing behind them, including a two-inch mortar and bombs for setting off avalanches with.

And yes, it's intriguing to read about an expedition where everything goes to plan, everybody behaves like a good old chap and nobody loses any of their toes.

But it's still, sadly, a semi-official account.

Among those scarcely mentioned in the book are Eric Shipton: leader of the previous year's explorations, invited to be leader of the expedition, but then uninvited in a rather shabby way. Shipton was a small-expedition, adventurous sort of climber: not at all what we want.

Also understated is the Swiss expedition of the previous year which had pioneered the route right up past the South Col to the 8600m level just below the South Summit. And, of course, no mention at all of George Mallory and Sandy Irvine, who didn't get to the top back in 1924, of course they didn't.

Being tidy minded and environmentally conscientious, they take care to jettison rubbish of every sort "on the down-stream slope", well below Base Camp. So that, right at the base of the Base Camp rubbish dumps, there may be a flattened layer of pemmican cans left by Ed Hillary himself.

And no, there absolutely wasn't a Sherpa mutiny over the working conditions.

On Everest Noyce was one of the strongest climbers – Ed Hillary called him "the most competent British climber I had met." And he was very much a team player. He spends the first month ferrying up loads. Followed, for the rest of the expedition, by ferrying up some more loads. Noyce does get a crucial bit of route-making, up to the South Col with Sherpa Annullu at a time when the rest of them were a bit demoralised. A second climb to the Col with 50lb on his back assuring that Noyce would himself be too tired to be considered for the top.

The book does contain a couple of indiscretions. The first man to the summit was, in fact, Hillary rather than Tenzing. And this was left unrevealed, not out of international solidarity, but because for Hillary "it sounded precious like swanking..."

Plus, of course, Hillary's own 'disrespectful' words to George Lowe on arriving back at the South Col: "Well, George, we knocked the bastard off!"

There's also a couple of interesting differences from expeditions of today. The almost casual way they wander up and down the Khumbu Icefall: they even set up an overnight camp in the middle of it. This being back in the days when nobody at all had got killed by the Khumbu icefall yet.

We could also note the prominence given to the fearsome obstacle on the final ridge, the near-vertical section known as the Hillary Step. The Hillary Step gets just two brief sentences: "a fine piece of climbing at that height, a wriggle up the fissure between rock and snow."

"They've done it," writes Noyce. "Good. Now we can go down. "

Wilfrid was, like his early companions Geoffrey Winthrop Young and Menlove Edwards, a poet in his own right – if perhaps not a terribly good one. The poems are expressive in a way the relentlessly positive account isn't: two of them being about plodding up the Lhotse Face at 7000m:

One two three four

Five six seven eight

Steps and my head

Falls a plumb weight.

One breath and two, the picture again

Is a silvered back-cloth

To release from pain.

Okay, it's not fair to judge a man on what he comes up with under hypoxia in a wet tent at 7000m.

Ronald's Substack essay-feed 'About Mountains' has just posted a comparison 'Everest 1953 vs Annapurna 1951'

- Mountain Literature Classics: The Wildest Dream by Peter and Leni Gillman 14 Aug

- Mountain Literature Classics: Harry Griffin, the alternative Wainwright 12 Jun

- Mountain Literature Classics: WH Auden's In Praise of Limestone 2 Dec, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog 15 Feb, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: Free Solo with Alex Honnold 29 Nov, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: That Untravelled World by Eric Shipton 3 Aug, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight 4 May, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Menlove 9 Mar, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North 12 Jan, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Conquistadors of the Useless by Lionel Terray 17 Nov, 2022

Comments

Somebody I was privileged to meet when a schoolboy. His book sits proudly on my bookshelf.

I'm fortunate enough to own George Band's copy of the book, together with his post-it annotations. On p253, where it is mentioned that Everest's "top had first been trodden by Hillary or Tenzing-which?", there is the enigmatic note "T on top". I wonder what that means??

(The book is also signed by Hillary, which is nice)