This article first appeared on Alexandre's Site: alexandrebuisse.org

Alpine Start

5:30. Both our alarms go off at the same moment. I had just found something resembling sleep in the decidedly not so comfortable bivy bag, but, excited by the climb to come, get up in an instant. It's too early to eat anything, but Dave manages to force a Scottish egg down while I lace my boots. We prepared the packs a few hours ago, when we reached the north face car park: a small rack, two 8mm ropes, our personal kit, a quart of water and some cereal bars, we're going light today. In less than half an hour, we are gone.

The path starts in a forest and goes steadily uphill. It takes me a little while to find a comfortable pace, especially with my huge Spantiks on the feet, but the walk in the dark soon becomes quite pleasant. After a little while, we reach the upper car park and a wide plateau void of any trees. In the distance, some lights close to the CIC hut let us know that we are not the only ones heading up the Ben.

According to the watch, the walk to the hut takes us almost two hours, but I don't really notice it. In the light of pre-dawn, the majestic and very intimidating north face is slowly unveiled, and I can't help thinking along the lines of "Are we really going to climb that?!". It's a far cry from the gentle slopes of the zigzag route taken by thousands of tourists every year.

As we reach the hut, the snow becomes deeper, but seems well consolidated, with no recent falls. Still, we hear half a dozen avalanches starting on the nearby slopes, and resolve to avoid gullies all day long, especially on the descent. Another twenty minutes of uphill slogging brings us to the east side of the Douglas Boulder. Between us and the summit stand 600 meters of snow-plastered technical rock. The climb is finally on.

Prologue

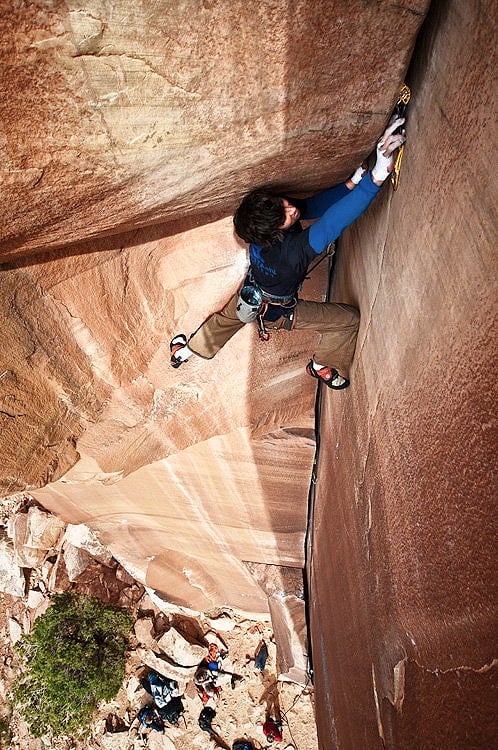

Last October, I was lucky enough to be invited to the AAC International Climbers Meet, in Utah, as a Danish Alpine Club member. We spent a week of amazing climbing in Indian Creek (leaving me with many gobbies, a sprained ankle and a huge smile) and Little Cottonwood canyon. But of course, the best part of the meet was to meet climbers from all over the world. Two of them were from the UK: Dave Brown and Andy Turner.

Fast forward a few months. As part of my PhD, I have to move from Copenhagen to London until the end of the summer. Though it's another big city, it has the advantage of being much closer to good rock and real mountains. Before even setting foot on British soil, I have contacted Dave again and we agreed to go do some of the winter climbing Scotland is famous for. He has much more experience than me, but is happy to go repeat what is probably the most famous route up Ben Nevis: Tower Ridge.

It's actually not the first time I try to go up the highest mountain of the UK. On my first trip to Scotland, a weekend two years ago, I tried to go up the tourist route but due to late snow, poor weather forecast and lack of crampons, I bailed an hour away from the summit. Reaching the top by a route as difficult as Tower Ridge would mean a lot to me.

Finally, on a Friday afternoon, loaded with warm clothes and winter climbing gear, I take the train to Sheffield, then meet Dave for the long drive to Scotland. It's almost midnight by the time we reach the promised car park and unroll our bivy bags. Tomorrow will be a long day.

On the ridge

Instead of attacking the Douglas Boulder head on, we choose the traditional way of traversing to it in an easy snow gully. There is a lot of snow, which makes upward progress a serious effort when breaking trail, but we are soon at the small gap, looking at a 10 meters high corner before we can reach the crest of the ridge. Because of the amount of snow, We decide to play it safe and belay, and while we uncoil the ropes, Dave asks me if I want the pitch. Until then, I had expected that, on the grounds of having much more experience, he would lead most of the technical ground, so I am most surprised to hear myself answer "Sure, I'll give it a go".

The belay is a good stance, soon backed up by a slung rock and, a bit further, a good nut. As I start climbing up the dihedral, I realize that there is no ice, hook placements are not many and all covered by a lot of snow. I make some upward progress on very sketchy feet when suddenly, both crampons cut loose and one of my tools rips off. I am held in place by friction of my body on the low angle rock more than by my remaining tool. With some very ungraceful movements, I manage to restore some sort of balance. As I glance down at a worried-looking Dave and at my last pro, a good 3 meters lower, the seriousness of the situation starts to sink in. This definitely isn't sport climbing, falling is absolutely not acceptable and I have to give this my full attention. No more jerking around.

Two more moves lead me to a high step on a small ledge, a hook on the exit of the corner and I am suddenly on easy ground. The first pitch is over. A few meters further, an in-situ sling around a conveniently placed boulder give me the perfect belay station. As Dave quickly climbs to my position, I am glad to hear him comment that the moves were harder than he thought.

In front of us now, the ridge itself looks quite easy, if very snowed up. We decide to simulclimb instead of soloing, as we predict that we'll probably need the rope soon, to overcome the looming tower that stands above us, impossible to ignore. Still a bit shaken by my stint, I gladly give the lead back to Dave.

The next section is indeed very easy, but due to the amount of snow, it is both hard and time consuming to find protection, and despite the generous length of rope we decided using, it becomes quite rare for us to have the required two pieces at all times.

We soon reach what we (incorrectly, as it turned out) believe to be the Little Tower, the first of the prominent features of the ridge. Knowing that the topo doesn't call for any traversing before the Great Tower, I argue that we should attack straight up, as a line seems doable, but Dave is of the opinion that much easier ground is to be found on the right hand side of the mass of rock. The amount of snow makes the traversing easier, though the only protection is provided by poor nuts hammered into shallow cracks. Dave disappears out of view for a while, then announces having found a good looking gully and the rope starts moving quickly. I follow, finding thin but good ice which allows fast movement. Running out of gear, Dave finally belays me from just below the top of the tower. The only thing left to climb: a blank corner.

He hands me the gear and I start optimistically, only to be stopped after a couple of meters. The corner is not very high, only 4 meters, but it is steeper than the previous one, both sides are completely blank and there is no crack to hook into. No gear either, though the belay isn't far away. I tentatively go up, looking rather desperately for anything to pull or push on, but to no avail. After messing around for a while, I stand on my frontpoints as high as possible and swing blindly over the edge. *Thunk*. The feeling is unmistakeable, I've hit good ice. Knowing how thin it probably is, I don't dare taking another swing. Gathering all my courage, I finally commit to the move. Supported only by my single tool, I smear my crampons on the right corner while dynamically high-stepping to the ledge on my left. Everything holds. Almost crawling and with an impressive lack of grace, I manage to wedge the right knee in the corner and finally to stand up. Phew.

In front of me, a gentle snow slope to a rock outcrop. I still haven't placed any pro, and my only is hope that the rocks will give me something to sling. I of course run out of rope two meters before reaching them. Luckily, we have both been carrying coils, and after a few minutes of fumbling around to drop mine, I finally manage to reach the promised belay.

We simulclimb the next snowy sections, with Dave back in the lead, when the solo climber we had noticed earlier catches up with us, having gone over the previous difficulties in just a few minutes (though probably using another line). It turns out that he is rigging a fixed line on the Great Chimney (IV,5) for the cameraman filming a re-enactment of Jimmy Marshall's extraordinary week, exactly half a century ago. And the two climbers coming up? Well, Dave MacLeod, one of the best climbers of the UK, and Andy Turner himself!

Unfortunately, Dave and Andy haven't started climbing yet when we reach the top of their route, and we can't afford to wait for them as we still have a long way to go. It's also my lead again. We are approaching the not very aptly named Little Tower, and in front of it, a corniced and narrow snow ridge. I cautiously walk across, half expecting to fall through with each step, but the deep snow holds firm and I soon reach the steep slope of the tower. A few rock steps later, I finally find pro with an in-situ sling around a large diamond-shaped boulder. Above, more rock with awkward looking steps. I hesitate going on, make a half-hearted attempt and finally decide against it, too tired mentally to ignore a good belay opportunity. I downclimb to the sling and finish bringing Dave up. Of course, he gets through the next lead with no effort, and we simulclimb again until he runs out of gear, at the top of the tower.

We are now nearing the summit, but most of the technical difficulties are still ahead, including the steep Great Tower. In an almost perfect mirror of the previous sequence, I get to lead over a scarily narrow snow ridge, then up the base of the tower. But since distances are a bit bigger, Dave has to leave his belay and start simulclimbing before I can find any gear. I try for a while to place nuts in various cracks at the bottom of the slope before finally accepting there is no decent placement and going on. The climbing isn't very hard, especially as ice appears much more frequently now, but I am acutely aware of the consequences a mistake would have for both of us. This makes me climb with more focus and precision than usual, and it is a bit frightening to now realise that it actually is one of my best memories of the whole climb!

After I sling a horn and reach the steepest part of the rock, it becomes obvious that we have reached one of the two cruxes of the route: the Eastern Traverse. And indeed, a very sloping and not so wide snow ledge looks us in the face. It is a bit difficult to find protection for a proper belay, but we dig out a decent boulder and Dave hammers an ok-looking piton which, combined, give us enough confidence. Plus, we won't fall anyway, right? Dave is actually enthusiastic at the idea of leading this, so I gladly hand him the rack and sit back to enjoy the show. He moves very cautiously but doesn't seem to find it difficult, as the deep snow is very supportive. He even finds good nuts every couple of meters. After a few minutes, he disappears behind a turn and the rope starts moving faster: he's now on easy ground, and soon tells me I'm on belay. Since we are traversing, it isn't necessarily safer for the second, but following tracks definitely is much easier! The only scary spot is a 2 meters downclimb to the edge of what looks like a cornice, but it's over quickly. I join Dave at a cool belay near a huge chockstone stuck in a chimney.

I can smell the summit and start my pitch with renewed energy, but soon meet difficulties. With a tied-off piton as only pro, I have three possible routes in front of me, each looking equally difficult. I try traversing to the left, but the rock steps are too high and would require some advanced acrobatics. To the right, then. I manage to get slightly higher but soon find myself in an awkward position, with the only way out being a notch between two overhanging rocks. Far above the belay and without much illusion as to the strength of my piton, I can't commit to the move. I try exploring further and finally discover a bomber nut, but my way out is still blocked. I spend a while more fumbling around, evaluating the consequences of a fall (not good) before finally swallowing my pride and asking Dave if he wants a crack at this. I downclimb to the belay, leaving the nut in place, and Dave heads up. Swinging far above his head, he hits good ice, then does a very awkward high step, manages to put his right leg above one of the boulder and, relying on its friction, finally gets up the rock. Of course, when my turn comes to try again with the safety of a top rope, I find that going slightly more on the left yields a pretty easy move...

We are at the top of the Great Tower. The infamous Gap is the only obstacle left, but I'm also exhausted mentally. Dave is still going strong, though, as always. He hands me the rack and, without a word, I take it. The gap is very close but we are now in the clouds and we can't see more than a couple of meters away. A small downclimb leads to a very, very narrow ridge. I recall photos of what this looks like in summer: rectangular blocks, no more than half a meter wide and unevenly spaced. With great care, weighing each foot slowly before fully committing to it, I finally reach the gap. As instructed, I clip into one of the many slings lying around, then sit à cheval on the last block and belay Dave.

I have seen photos, of course, but I wasn't prepared for what was in front of me: a tiny ledge below the overhang of the boulder I am currently sitting on, then a good horizontal meter of pure air before another small ledge and a high vertical step. On our side, plenty of old tat, but the only gear on the other side of the abyss is an old fixed nut. At this point, it is fair to say that I am terrified. So I do feel very relieved when Dave, having joined me, asks for the rack.

Since leaving the soloist at the top of the Great Chimney, we have been completely alone on the ridge, but this is about to end: a rope is already in place in the steep right hand side gully of the gap, Glover's Chimney. We wait a few minutes for a climber to emerge from the fog, scale the end wall of the gap and disappear higher up, lost in yet more clouds. It's our turn. Dave steps over me, then I give him tension as he drops on the invisible ledge, hidden by the overhanging rock. Without much hesitation, he bridges to the other end of the gap, sinks his tools in good snow and commits, bringing his body entirely on the other side. A few easy moves later, he's safely over the last obstacle. He keeps going for a while, looking for a good belay for his scared seconder.

Before I can follow, however, another party emerges from Glover's Chimney. The leader, though moving quite gracefully, mentions that this is his most difficult climb ever and that he wouldn't mind things to get easier soon, which immediately wins my sympathy. I point to the fixed slings I am already belaying from and he joins me. He tries to bridge the gap but doesn't want to fully commit, so instead offers me to go first, which has the advantage of avoiding any tangle of ropes. Dave signals the belay is ready, I have no more excuse. Still scared, I unclip from the belay, sink my ice tools upside down in the snow on the far side of the boulder, the only decent placement to have, then drop down blindly. I can't find the ledge for my feet but pull on some of the slings (there goes my free ascent) while keeping my left hand grabbing the tool by the knuckle fang at the very bottom! A bit stuck and still not really knowing where to go, the other climber guides my foot until I can finally stand up more or less safely. The hardest is yet to come. Just as I saw Dave do, I fork to the other end, pushing my flexibility to its limits, then get two good ice tools on the next boulder. Extended horizontally, I just need to bring my weight on the other side and I know I'll be done. I close my eyes, gather what's left of my courage and commit to this leap of faith. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it's actually a pretty easy move, and I find myself smiling on the other side before I realise it.

The other climber has been observing carefully but he still doesn't feel too confident, so asks me to clip his rope on the fixed nut. Services trading high on alpine ridges is fun! I wish him good luck and scale the last rocks to the belay. We revert to simulclimbing as the terrain is now easy, but we won't actually find a single gear placement before the summit. It takes barely two rope lengths on easy snow slopes before we top out. It's 14:45 and we are higher than anyone else in the British Isles!

Epilogue

The weather isn't too bad, but we still can't see very far away. We take a half hour break on the summit, eat some well deserved chocolate, stow away ropes and harness and finally begin our descent. Because of the avalanch risk, we decide to take the tourist route instead of the traditional gullies. Navigation from the top is tricky, as expected in a whiteout, but with the help of both compass and a series of huge cairns, we find the descent route without too much trouble.

It takes us three hours to get back to the car, through snow, scree, pathless bog and finally forest. As we reach the car park left 13 hours earlier, night has just fallen. We are knackered, hungry and thirsty but most of all happy. We had just completed an amazing route in good style, and most importantly, we had had a lot of fun!

This evening, we head to the pub for some hot food and celebratory pints. Still exhausted, we crash before 21:00, bivying in a Glencoe car park. The next morning, we head to the much mellower Curved Ridge (II) on Buachaille Etive Mor, probably the most photographed mountain of the UK. We solo, pitch and simulclimb in equal proportions in a whiteout until we reach the summit in terrible winds. Without even stopping, we head down an easy gully which brings us back to the base of the mountain. Roundtrip in less than 6 hours, and a perfect conclusion to a weekend of climbing and friendship in Scotland.

- Remote Exposure: A Guide to Hiking and Climbing Photography 30 May, 2011

- A Guide to Mountain Climbing Photography 4 Feb, 2010

Comments