CIMA GRANDE: An adventure in 1976

The day began well and stayed that way until nightfall when things went downhill. Considering the magnitude of the problem facing us, an early night might be in order, instead of the usual debauchery. Almost asleep by 9pm, the relative peace was broken by the late arrival of a team whose campcraft was less than polished. Neither were they briefed about our programme. John began that process from the confines of his tent but this made little impact on the noise level. It took a while but the notion of us using an ice axe as a surgical instrument eventually sank in - luckily before the axe did, and an uneasy peace settled on the campsite.

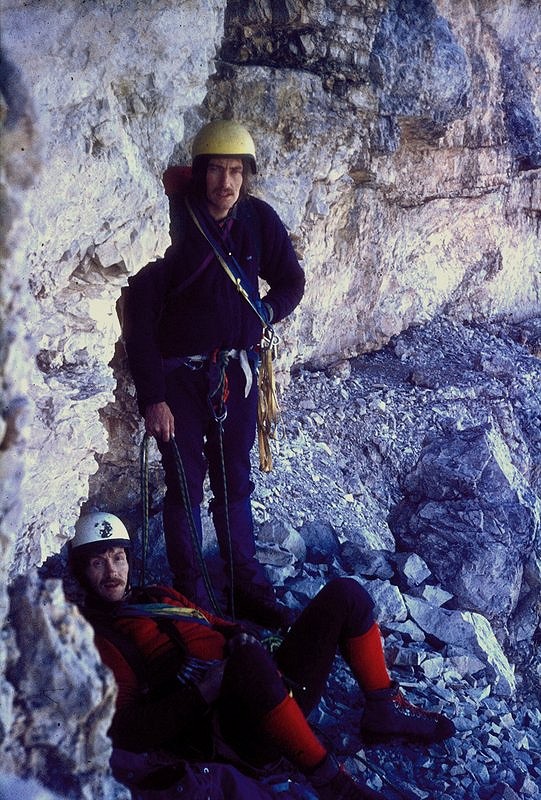

We were camping at Misurina, above Cortina in the SestoDolomites, about to embark on our first major objective of the summer, the Brandler Hasse on the North face of the Cima Grande, also known as the Grosse Zinne. Climbing as a rope of three were John Barker, Ian Blakeley and I and we had been practising, making a reasonable account of ourselves on the Yellow Edge, only losing our way on the descent, in the dark. John likes his sleep in the morning. Ian and I had also been up the N.E ridge adjacent to the north face and sharing the same descent.

No one had been on the Brandler that summer and it was reported to be cleaned of much of the fixed equipment that difficult and notorious climbs accumulate. The weather had been poor and the winter very cold. A build up of ice in the top chimneys was probably putting parties off. They were waiting to be shown the way. At around 1700ft high the face is vertical and slightly overhanging for the first 700ft. Some small broken ledges mark the beginning of the 300ft overhanging section. After another small ledge, the rest is merely vertical. Only two ledges on the route! It looked awesome from the bottom and stonefall regularly raked the snowpatched scree. Hard to see, the small ones whined like bullets and the larger thrummed through the air and hit the ground well out from the base with a horrible sound. You could occasionally catch sight of these in their plunge. The sheer destructive power and potential for damage to the human form is sobering. The quality of rock on the wall is not so good, the wrong colour according to the guidebook. All these negatives being enough to start one thinking about a package holiday and a beach.

It was cold and grey as we hiked round to the base of the route early next morning. The view towards Austria was veiled by falling snow. Being still tired and apprehensive it would be easy to call it off in such unseasonal weather. Of the six big north faces in the Alps this has the easiest approach and we could get off this first section safely if the weather worsened. A three way discussion resulted in a positive decision; onward.

Three is an unusual number to be climbing such a serious route. Slower than two, it is also difficult to find ledges big enough for three (we had to split up on the second night on this route and later with a different team on the Walker Spur). Abseiling takes longer and rope management needs to be perfect. However, there is more scope for humour and democracy as well as less climbing hardware to carry.

The route starts with a bang after negotiating the rotten yellow rock at the base. Free climbing alternates with sections of aid and the exposure soon snaps at your feet.

The rock is quite brittle and fairly featurless. Route finding can be tricky as the old tat of false starts and abandoned dreams litters the wall. After 300ft we came across a challenge. A blank section had been overcome by drilling small holes, about the thickness of a pencil and perhaps an inch deep. A wooden plug had been inserted and a small coach bolt with an eye screwed up tight. I was about ten when that had been done. Time and use had loosened these plugs, five in a row spread over 25ft. We sacrificed precious toilet paper to pack and reinsert the screws. It was quite tense. They could have easily ripped and unzipped. Careful and precise movements were the order of the day. On other sections there were a few pitons but they were not good either (the good ones had been removed) and we treated these bent and rattling specimens with caution. Our own gear was better designed and chromolly steel, mostly from America, where big granite walls had dictated their development. The brittle limestone here required subtle placing or the rock just shattered. The softer European pegs bent into the shape of the cracks. Overdriving with both types was not desirable but sometimes the fear factor gripped and it was difficult to go easy.

The first part of the wall trends left and we three are right handed. Aid or artificial climbing is awkward in these circumstances, the pitons are easily dropped at the onset of placement and with the last few taps of removal. Tying them off to a long bootlace onto your harness meant yet another item to become tangled but kept the precious goods in our possesion. Moving from direct aid, ie, hanging from pitons and slings, to free climbing always feels precarious as you are hindered by the extra gear. John was leading with his sack on and fully deserved the high regard we had for his ability. Ian and I climbed together a few feet apart unless the going was so hard we were likely to be falling off. All the stances were hanging and uncomfortable, the best harness in the world hurts after a few hours.

By late afternoon we were nearing our destination, the small ledge system under the big overhangs. The last pitch leaned the wrong way again and it was a relief to crawl onto the ledges, however precarious and exposed. We constructed a ropeway to move around whilst remeaining clipped on. Lying down was possible but you always had an arm over the edge. Sitting was ok but your legs dangled. Moving a few rocks could make a big difference to sleep. A good night and you can face anything. Above, tomorrows' journey was mapped out by the dot to dot of piton heads disappearing up to the right in an understairs view of treaders and risers constructed of giant pieces of limestone. Somewhere up there was the crux, written about by Bonnington following his ascent, the first British, with Gunn Clark in 1962. The view north stretched from the screes at our feet, colonised by vegetation lower down, then woods and an open vista towards Austria. A few people could be heard and sometimes seen. We had a leisurely tea, shadows lengthened, the voices drifted away and silence returned to the cathedral apse. It would have been good to have more water for brews but I felt fine if a little overawed. We got into our sleeping bags, John had his down jacket reasoning that if the weather turned bad you could not climb or abseil in a sleeping bag. We slept tied on. This is no place for sleepwalkers. Sleep came slowly despite tiredness as the void hovered an inch away, you could not put it from your mind. Next thing, someone was shining a light in my eyes - blurry, not sure where I was for a few seconds. The light became the moon and mind and body, having relaxed in the safe haven of sleep, returned onto what surely is one of the least desirable holiday venues in Europe. The landscape glowed and a massive deep inky shadow filled the gap between the Grande and the Ovest. I photographed the scene then tried to get back into the refuge of sleep, hindered by anxiety about tomorrow. I tell you it's not easy, this game, for a person of imagination.

Fatigue must have won through as my next memory is of a new sun slanting through the peaks to the east. You cannot put off the inescapable truth that to return to your earlier existence from a place like this, you need to get going with some conviction. So we did that and rose slowly and with a new rhythm of climbing that was lacking yesterday. It was all overhanging, good corner cracks out and along and then out and along again. We were way above the ledges, the ground a distant memory. Falling stones were uncomfortably close now as we neared the edge of it all. We passed a half boot sized hold where Bonnington had been benighted and near there a small plastic label fastened to a piton, removed from an Italian railway carriage. It read,"I PERICOLO SPORGHESE" or, "It is dangerous to lean out of the window".

After three pitches the lights went out, quickly. We were marooned on a vertical desert. No ledges, just grooves, cracks and an endless abyss. John and Ian found an open groove above my version of the same and we shuffled around in the gloom with ropes, slings and pitons to create a safe "hang" which is what you might call a place where bats sleep. Very carefully I got my sleeping bag out without dropping anything else and organised it inside my rucsac so that I could pull them both up to my waist and fasten the sac off to an anchor. Now, not all my weight was on my harness and my body heat, so easily lost through thigh muscles, was conserved. I actually slept for a while.

By and large the rest of the night is best forgotten and I think the other two would echo this sentiment. A slow grey dawn revealed a cloud-cloaked world, dropping away into infinity. Bacon, eggs and coffee would have been lovely but we made do with some mucky bits of icicle that John, in a crazy moment, traversed off to find, unroped. This just made our thirst worse and when John eventually started climbing, having drawn the short straw again, he turned round and threw up over Ian and I. After apologising for that he then announced that he needed a piss and I'm sorry lads but I know you're directly below and unable to move. We got the full benefit of that as well. Thick and aromatic it was too, on account of the exercise and dehydration.

The climbing was certainly interesting, not as hard as below, but in our state, still taxing. A big, iced up chockstone across a chimney was memorable but the ice was retreating and falling off in lumps as the day warmed up.

All good things come to an end and so it was that the sun came out and around about midday we hauled our painful way onto the summit ledges, castaways after a few days at sea. Flat ground! So that's what feet are for. We revelled in it. The utter relief of it, the void no longer that constant, insistent force pulling at body and soul. I looked closely at my partners in this madness and they looked so old, skin shrunk round their skulls, that I was inspired to lift my camera lest ever someone, one winters night, in the comfort of a West Riding public house which brews its own beer, says, "I have a little project in mind for next summer, right up your street".

Related article: Brandler-Hasse - F7a+/E5, by Jack Geldard on UKC

Comments