UKClimbing.com periodically run Guest Editorial articles from experienced climbers. Recently we have had pieces from climbers such as Pat Littlejohn, Dougald MacDonald and Nick Bullock. These opinion pieces are written from the heart, with passion and feeling. They are not official UKC policy, but they are of interest and value to British climbers. If you would like to work with UKClimbing.com on a guest editorial, please get in touch.

Regarded by some as being too small and just a distraction from 'proper' trad climbing, whilst at the same time, treasured by others who revel in the short solos and smeary friction climbs, gritstone, like it or loathe it, is central to the UK climbing scene. Its small stature is more than made up for by its peculiarities and often blank and gearless nature.

In this editorial article, experienced climber Graham Hoey, who has had a 35 year love affair with the gritstone edges of the Peak, explores the ever advancing style of gritstone climbing, for better or for worse...

Graham has experienced some hard grit himself, with his own ascents, on sight, up to E6, and more recently by belaying James Pearson on the first ascent of The Groove at Cratcliffe Tor.

Here he shares his opinions on the current 'state of play' on gritstone.

A gritstone retrospective

by Graham Hoey

With a flurry of ascents of some of grit's hardest routes, the level of gritstone climbing has recently hit new heights. Or has it? How much have on-sight standards really improved in the last twenty five years? Is the current wave of activity the tip of an iceberg of high quality ascents in good style across the entire grade spectrum? How much bolder have climbers become?

In developing this article I spoke to a number of climbers, all with a passion for climbing on gritstone and with a strong record of commitment. Dave Thomas in particular has spent considerable time thinking about the manner and psychology of bold ascents. Dave has many serious solo ascents of (protected) E6 routes to his name including Lord of the Flies, Sardine and Cave Man/Terra Cotta.

For him, “a route is not defined purely by its material nature but includes the manner or style of ascent”, what some are beginning to call 'the experience'. He argues that “The material fact of the route does not exist separately from our act of climbing it. Therefore, it only exists, along with our opportunity to emulate/surpass the achievements of our forbearers, only in the MANNER or style of our ascents. This is critical”.

Dave (like me) “draws inspiration from the actions of those before us, reflects on them and seeks to move forward”. He feels that “many climbers attempt to stand on the same pedestal as their contemporaries without considering the manner of their attaining it...and that if all they extract is the hard, material part, and not the full experience, they will never understand the journey involved in attaining the top of the pedestal”.

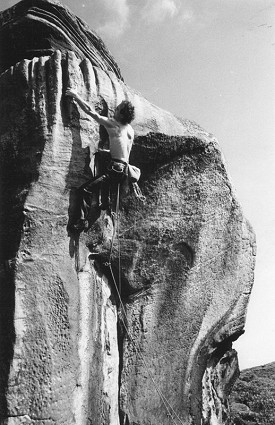

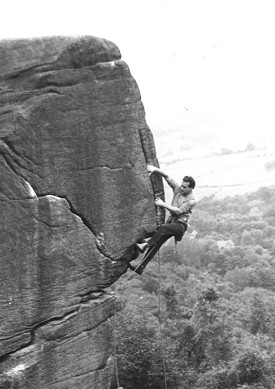

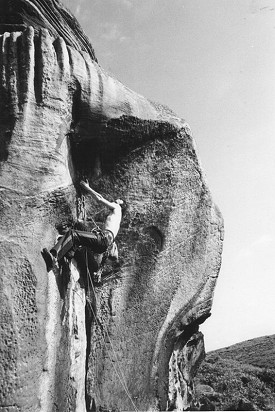

PHOTO: These photos are me on-sighting Barbarian at Bowden Doors in 1984. There was some debate recently (July 2007) on UKC as to whether this had been on-sighted. If I recall virtually no one thought it likely!

“The challenge isn't determined by what we climb but how we climb it and we should always ask ourselves "have I really faced up to the challenge? Can I improve on the style of my ascent?” I concur with his view therefore, that most hard routes (including those on gritstone) are yet to be repeated in what used to be simply known (and clearly understood) as good style and that pre-practice and pads remove the 'soul' from a route; leaving only the 'lifeless corpse' (the soul being found in our encounter with it).

For example, on Gaia, because of his height, Johnny worked the entry move to the groove finding it English 7a; he didn't practice the upper section at all. Dharma (E7 6c) was cleaned on abseil, but no moves were attempted and he then flashed the route.

On Avoiding the Traitors (E7 6c), Johnny fell off a number of moves while on top-rope, failing to link them at all. He then elected to solo the route. It was only the photographer's request to use a rope to 'improve the photographs' that made him lead it! Most of his unprotected routes were done without any landing protection, although on Angel's Share (E8 7a) he did pile up some Birch twigs and on Charlotte Rampling (E6 6b) he tried to fabricate a 'safety net out of a rope'!

Repeating these routes in good style back then was the preserve of the truly talented, and for many years they received few, if any, such ascents. For example the 'second ascent' of Dharma followed top-rope practice.

Scroll forward 23 years, over two decades of indoor climbing walls, campus boards and red pointing; climbers have never been stronger. Have on-sight levels increased significantly? At the top level, among the masses?

Grit E4s were being on-sighted in the 1970s. E5s in the early 1980s (most quality bold E5s had been on-sighted well before the mid-1980s) and E6 by the mid-to-late 80s. They were often done mid-week, alone, on deserted edges (without shit out ropes, pads and mobile phones) and were committing experiences. I mention this because there seems to be among many younger climbers (and those new to the sport) a general lack of awareness of the style of ascents over the last 20 years.

Even now, two decades on from these ascents, why do bold routes of these grades seldom receive on-sight (padless) ascents? Furthermore, why are ascents of E6s being reported as significant? Recent examples include an ascent above pads where the E6 nature lies in the bad landing below a relatively low, unprotected crux (done ground-up padless 16 years ago), a head-point of a well-protected E6, a very minor new E6 and an on-sight of an E6 in Wales (on-sighted at least 15 years ago). Climbers even ask on forums whether certain routes of E5 have ever been on-sighted!

How did we get to this? In 1998 the Hard Grit video was released. For the past ten years following this release, head pointing has been the predominant way of attempting the harder routes. Before long nearly every man and his dog were practising climbs on a top-rope.

Leading grades increased but what about standards or style? It was easier, and gave more kudos, to head point E8 than to on-sight bold E5s and E6s. For most climbers, applying an on-sight ethic to the harder routes was ignored. Getting better meant having to wait.

To quote Andi Turner: “It's the same old story, lines are opened after practice and the practice is justified by their difficulty. Years later the routes are flashed/on-sighted/ground-upped and we've caught up with ourselves again”.

Many even extended the head point approach to routes which are well protected! In the vast majority of cases, the top routes of the eighties were being (and are still being) ascended in worse style than when they were first done. When in the history of climbing has this ever happened, and why has this been viewed by many in the media as progress; with some of these ascents being reported as significant?

Only a few talented climbers have equalled or improved upon the efforts of the first ascentionists of these upper end routes.

An argument used to counter concerns about head pointing is that as long as it doesn't do any harm and people are honest about their ascents then it doesn't matter. But is this really the case? Unfortunately many climbers who head point repeatedly practice routes. Take a look at Kaluza Klein if you want to see what repeated top-rope practice and brushing can do. Compared to when it was first done it's trashed.

As a case study it is interesting to consider the manner of the first ascent of Master's Edge in 1983. Ron Fawcett abseiled down it and brushed Jerry Moffatt's chalk from the holds, but didn't try any moves. The protection available was an unproven prototype camming device and a tri-cam (hardly a confidence-inspiring combination!) and he didn't pad out the landing. The rock was wet at the start and on his first attempt he fell off when a damp boot slipped out of one of the shot-holes. On his second attempt he succeeded. In the past 26 years how many ascents have matched this? Perhaps more importantly, how many have attempted to match it or improve upon it?

Conan The Librarian - The best E6 in the country?

However it took quite a time (helped by some egoless talented young Brits and some honest American visitors) for it to be finally accepted that they do reduce the E grade and challenge of specific types of gritstone routes and that the reduction is indefinable.

At long last, common sense has prevailed and bouldering grades are starting to be applied when pads are used. What I do think is important is that the use of such pads is reported accurately by the media and in guidebooks. Why are some ground-ups where pads have been used being given E grades in reports?

I read recently that “the E8, Angel's Share had been climbed ground up”. No it hasn't, not as an E8. The experience that is Angel's Share, that first realised by Johnny Dawes is not obtained above a platform of pads. Adam Long openly declared his ascent as a high ball problem, and no one watching the video of the ascent can doubt that without pads Adam would have soon been on his way to hospital.

It's been said that pads are the new cams and that not to use them is just being stupid. This is surely nonsense; isn't protection whatever is available on a route, not under it (yes, the development of cams has enabled certain routes to become easier, but the slots have to be part of the route; pads are non-discriminatory).

Such statements are attempting to redefine what bold gritstone is about, an attempt to justify what really doesn't need justifying except from a warped sense of ego. It can't change the simple fact that padded ascents are less challenging, not the full experience and not in Dave Thomas's definition 'the route'.

Now, it can't be denied that climbing above pads is good fun, and where they are similar to cams is in enabling climbers to have a better experience than top-roping along with (an indefinable) risk. Clearly, pads don't guarantee safety, but they are definitely a better bet than the ground!

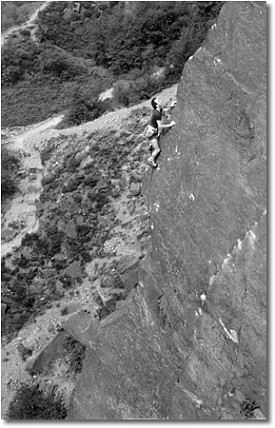

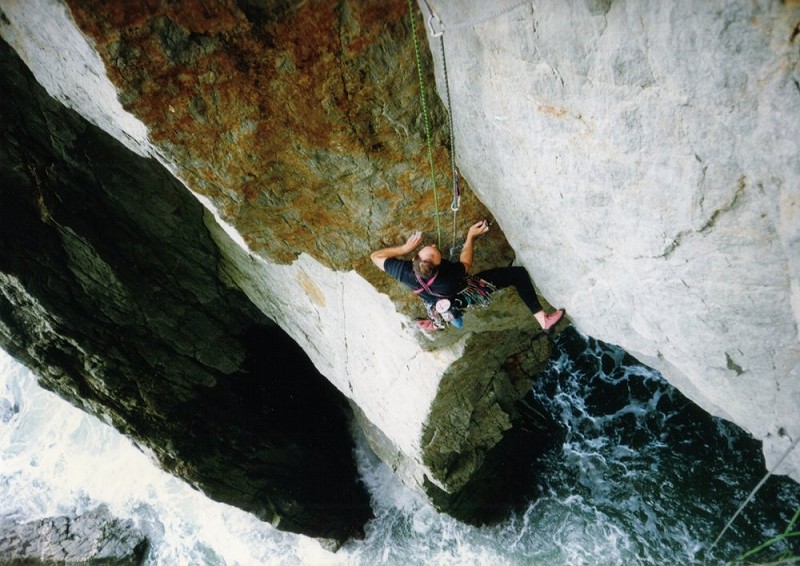

PHOTO: Old School pads. Me attempting an early on-sight of Pirhana (E6 6b) in Water-cum-Jolly (1980s) above a folded karrimat. The attempt ended in hospital!

However, one of the beauties of gritstone has always been its relatively low height allowing significant doubts when doing bold routes with deck-out possibilities. Indeed, the complete challenge is in having the mental and physical abilities to overcome these doubts. I do feel it's a shame that some people are missing out on the incredible experiences these challenges represent.

Leo Houlding, reflecting on serious climbing stated (I forget the exact words) that it wasn't that feeling of danger experienced on the route that was important, but where the experience took you. If you want a full feeling of the commitment gritstone offers (which has always been an important element in gritstone climbing) why not consider ditching the pads now and again? It can rather worryingly get addictive!

By the way, pads are not a new idea; they were available in the 20th century (as mattresses) but were considered to be cheating, only a car mat, beer towel or ¼” thick karrimat considered fair sport! For example, when Pete Cresswell soloed Scritto's Republic above a landing padded out with ropes, rucksack and an abandoned car bench-seat the ascent was not felt to be particularly significant, (some may say he was ahead of his time!).

People say this makes no difference to this route, but which section would you like to fall off least, the start or the finish? Apart from an incident where gear was placed poorly in the shot-hole, no-one has hurt themselves off the upper part, but Mike Lea ended up in hospital when he fell off the start without a pad!

Finally there's the issue of using pads for first ascents of the few remaining last great challenges. One prolific gritstone new-router from the 80s commented that

“Multiple pads on first ascents would certainly piss me off because my generation could have done quite a few more new routes with pads, but left them for climbers with bigger balls in the future. I did the moves on The Promise, but didn't feel inclined to lead it. I didn't spot the runner, good effort to James for doing it without pads. I think that repeat ascentionists not using pads should have the right to rename and regrade the route.”

Should these challenges be left for those with the ability and mental strength to do them without? Would renaming and re-grading the route when repeated without pads be reasonable? What about the first on-sight repeat?

A desire to move away from head pointing towards the on-sight has led to the ground-up approach (which many older climbers would argue is nothing new!).

Coming close on the heels of an on-sight, a ground-up ascent is considered the next best thing. But how does a ground-up solo above pads compare with head pointing? Andi Turner feels that “taking multiple falls from Ulysses above pads to claim a ground-up is barely different to a head point”.

One concern I have is when ground-up attempts involve repeatedly falling onto crucial and limited gear placements. The outer skin of grit is not strong and wears away to leave soft rock. In tiny, narrow slots where the contact area is small (and hence impact pressure of falls is large) the placement will get damaged and become useless.

I heard a rumour that following repeated ground up attempts on Parthian Shot, the flake had to be eased apart to remove a stuck nut (speaking of Parthian Shot, how many ascents have matched John Dunne's original of 20 years ago?).

How different is repeatedly taking safe falls (experienced by many non-climbers as bungee jumps) from top-roping a route (which will not stress the placement(s))? How long before one of the best hard routes on gritstone becomes lost for years to come?

To conclude, gritstone routes are a finite resource, a precious environment upon which we derive our pleasure. We have a responsibility to ensure that, as much as is possible, they are preserved in a good condition for other generations to enjoy.

Regarding the style of ascent I'm not suggesting that pre-practice or using pads is disrespecting our climbing heritage in any way; the disrespect comes when climbers make false or misleading statements about their ascent or the media choose to ignore the poor(er) style of the ascent in their reporting of it.

In addition, the history (which includes improvements in the style of ascent) of a route should be respected and celebrated. This requires a thoughtful (and retrospective) assessment of ascents and the media/guidebook agencies must be more proactive in this (and climbers possibly need to be less shy!).

Surely these agencies have a responsibility to maintain and improve standards by not reporting/celebrating ascents which fail to match or improve upon the style of the original ascents? Indeed are they not slowing down or reversing progression when they do the opposite?

We must therefore distinguish carefully and recognise when ascents have been truly significant (inspirational), for example Neil Gresham on Meshuga, Toby Benham on Soul Doubt (and others), Jordan Buys, Nick Sellers and Pete Whittaker on lots and James Pearson's on-sight of End of the Affair.

Where will some of the recent impressive (ultra) highball ground-ups by Ben Bransby, Ryan Pasquill, Pete Robins, and James McHaffie et al fit into the development of gritstone climbing? With this type of ascent are we witnessing the evolution of a new style of gritstone climbing? A style which offers the opportunity to on-sight moves close to the cutting edge of technicality, but with a greater degree of safety than hitherto experienced (in a leading/soloing sense). A style whose development and history surely needs be assessed (and celebrated?) in its own right, and not in the context of padless ascents?

Also, what role will this style of ascent play in the progression of gritstone climbing within the context of what has previously been achieved? Is it a step forward, a means to an end or a temporary lateral move?

At Hen Cloud hard repeats have all but dried up, an observation Andi Turner ascribes to the difficulty of padding out routes and/or finding top-rope belays. Is this the beginning of the end of padless on-sights of bold gritstone routes?

Graham Hoey 03/02/09

Thanks to those who made comments and helped clarify my thoughts, including: Dave Thomas, Tom Briggs, Al Williams, Andi Turner, Ron Fawcett, Tom Randall and Percy Bishton.

A big thanks to Ian Smith, Keith Sharples and Mike Waters for letting me use their photos.

He has cut his teeth on extreme routes throughout the country, leading trad routes on-sight up to E6 since 1984. This includes leads/solos of most worthwhile E5s on Peak grit. His hardest grit on-sight is the E6 Committed, which he climbed in 1986.

He has made numerous first ascents on grit including No More Excuses, DIY and Shirley's Shining Temple Direct. (Stanage).

His favourite style of climbing is adventure routes in mountains and sea cliffs. Particular ascents that stand out are early on-sight repeats of routes such as Midsummer Night's Dream (Cloggy), Cave Man (Berry Head), Ocean of Emotion (Little Orme), Guernica (Carn Gowla), Conan the Librarian - Janitor Finish (Gogarth), Meridian (Gordale), Bucket City (Dove Crag – Lakes) (all E6), Vulture (XS) - (Lleyn Peninsula). Second ascent (after cleaning) of Hellbound (E7) North Devon (2004).

Graham has re-cleaned and re-geared a number of routes throughout the UK, and recently made the first link of Missionary/Maze girdles on Red Wall (Gogarth) to give an 8 pitch E4/5 in 2007.

Graham dallied briefly with grit headpointing in 2003 doing 7 E6's and 2 E7's – "quite good fun, but not ultimately satisfying".

He has spent 29 years working on climbing guidebooks to the Peak District.

He lives in Baslow (Derbyshire) and is married with two Offspring (E5 6b, Burbage North)... ;-)

- ARTICLE: The Day the Music Died - Remembering John Allen 27 May, 2020

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Leonidio Limestone 9 Mar, 2017

Comments