How the Leeds Wall Changed Climbing History (And how to excel at whatever you want)

How many climbing wall users know that the very existence of their local wall - and the popularity of walls generally - came from one brick wall, one climber and one route?

Most of the significant developments in rock climbing over the last forty years can be traced back to this unique occurrence.

The kid from Nowheresville

I'd like to tell you a story. It's a story which will be familiar to some of you, at least in part. And that's all to the good. It's a story which fascinates me. For a while I thought I understood it, then belatedly realised I was a long way short of understanding it. It's a story which runs deep and far and wide, with the power to affect every last one of us. And it's a story in danger of becoming forgotten.

For me, the story began in 1966 when, as a 13-year-old, I started climbing, in Ireland. The term 'backwater' scarcely does justice. There were only about thirty active climbers in the entire country. I didn't know any of them. There were no climbing instructors or courses that I could find. No climbing magazines. No climbing shops – just the front room of caver Derek Jackson's mum's house. (Bless you, Mrs Jackson!) The Mournes guidebook was out of print. There was a well-established climbing club which wouldn't touch me with the proverbial barge pole (far too young) and a breakaway club of rumbustious characters, from the other side of the sectarian divide, whom I didn't dare approach. All in all, the outlook was bleak.

But life never has only good bits or bad bits; always it has both. Back in those days, long before savage, Thatcherite public spending cuts, libraries were as well stocked as premier salmon rivers. There was no shortage of climbing material; I devoured it. When someone suggested I read a book about climbing, they received the swift riposte, "I've read twenty-six!"

Got no climbing gear? Got no experience?? Got no mates???

Never mind - just go out and make it happen!

There were two leading instructional books. Alan Blackshaw's 'Mountaineering' was the bible of good practice, pretty much what you'd expect from a highly competent senior civil servant. But crucially I only discovered it after the delightful 'Let's Go Climbing!' by Colin Kirkus. The implicit message of 'Let's Go Climbing!' was disarmingly simple: Got no climbing gear? Got no experience?? Got no mates??? Never mind - just go out and make it happen!

So, as Kirkus had done long before, I went out and made it happen. I had no way of knowing that Colin Kirkus had been the boldest climber of his (supremely bold) generation. I had no way of knowing that he and his mates had been collectively referred to as 'the suicide club'. And I had no way of knowing that it had ended in tears.

At least Kirkus had the good sense to solo on relatively stable mountain crags. Not knowing any better, I soloed in chossy, disintegrating quarries and on chossy, disintegrating sea cliffs. If you were going rock climbing, well you climbed any old piece of rock… didn't you? It never occurred to me that what I was doing was about as dangerous as alligator wrestling while gargling nitro-glycerine.

Serving your apprenticeship…

…muddy flesh whittled with a scalpel and no anaesthetic

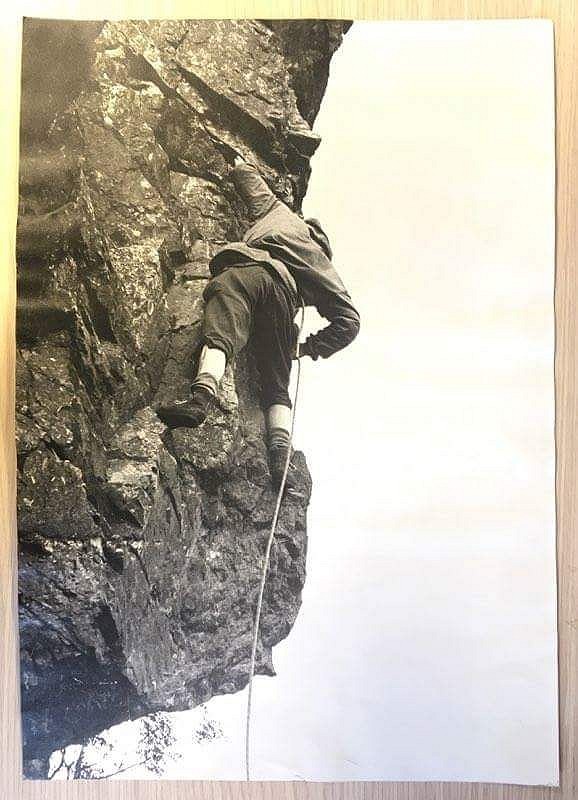

Very occasionally, capricious fortune rewards the supremely reckless with little more than a resigned, benign smile. There were so many times when, by rights, I should have died. Yet somehow I survived. Eventually I met up with other, much older climbers and started to learn from them. Although their experience was limited, I'll always be grateful to them for taking care of me as best they could. From 1966 to 1970, I slowly and painfully 'served my apprenticeship' as the late Ken Wilson was wont to put it. By 1970, when I was 17, I was tentatively entering the ranks of VS climbers. Back then, when most leads were pretty much death leads - certainly in the Mournes - the now lowly VS grade required a steadiness which is well-nigh unimaginable today. It was the hallmark of a competent climber. In fact, for most competent climbers, it marked the zenith of their careers. HVS was generally regarded as too hard, XS an unattainable dream.

Although my introduction to climbing was particularly difficult, due to being in such a pronounced backwater, it wasn't so far removed from the experiences of many others in England, Wales and Scotland. Nearly all of us came to climbing via hillwalking. We were accustomed to being cold, wet, hungry and sometimes lost in the hills. We slept out under the stars with heavy, yet poorly insulated and easily soaked sleeping bags. We hitched to and from the mountains in all weathers. We saw ourselves following the traditional model of hillwalking, leading to rock climbing, then ice climbing, followed by Alpine and perhaps Himalayan forays. Rock climbing was viewed as a primary skill in mountaineering, rather than an activity in its own right. How did you get better at rock climbing? Well you 'worked up the grades'. (Apparently Cliff Phillips was allowed to go up only one grade a year by his mentor.) What if you pushed yourself? When I pushed myself, I tended to fall off. In my first five years, I fell off a then scandalous five times. The first time should have been safe enough because I was seconding. Unfortunately my bowline was incorrectly tied; somehow it remained intact as I swung helplessly into space (yet another example of fortune favouring idiocy). But, on the other four occasions, I was either leading or soloing. All four falls were groundfalls - two from between thirty and forty feet. And they hurt. I have vivid memories of my forearm being ripped open on a remote Mourne crag. That evening, a local doctor whittled muddy flesh with a scalpel and no anaesthetic.

The key question -

How do you actually get better at rock-climbing?

Looking back, some fifty years later, it's obvious that 'working up the grades' was a model of 'assumed' development. I say 'assumed' because it begged the key question: how do you actually get better at rock-climbing?

Could there be a better way of doing things? When I started climbing, I pondered whether gymnastic ability and/or finger-stamina were relevant. I'd no way of knowing that world-class boulderers such as John Gill, Pat Ament and Greg Lowe were all ex-gymnasts. I knew nothing of gymnastics but diligently trained finger-stamina on the walls of an abandoned farmhouse near Newry. I had no way of knowing that Lawrie and Les Holliwell were training similarly on southern sandstone. Al Rouse was training similarly on Cheshire sandstone. Tom Proctor was doing the same as me - but much harder stuff - on the walls of outbuildings in Derbyshire. The Holliwells, Rouse and Proctor would all emerge as leading climbers. Me? Once I left boarding school in Newry, all my climbing was in the mountains. I was learning 'on the job' – with groundfalls. It simply didn't occur to me, or anybody else I knew, that there might be a better way.

There are nearly always better ways.

Most of the time though, we just don't see them.

Of course I know now that, in pretty much everything, there are nearly always better ways. Most of the time though, we just don't see them. And I certainly didn't see them. I remember meeting a group of Venture Scouts on their first day's climbing in the Mournes. They told me there was a climbing wall in the gym of their school in Belfast. Was it any good, I asked eagerly? Not really, they replied, cruelly dashing my teenage hopes. It seemed to involve pushing wooden pegs into holes in the wall and pulling up. Ironically people might do this now to increase their core strength. But you didn't really need core strength back in 1967 (there were very few steep routes) and pulling on wooden pegs just didn't seem particularly relevant. "So does anybody use it?" "No," they assured me. It seemed as though this wall lay sad, neglected and forlorn, a tribute to poor design.

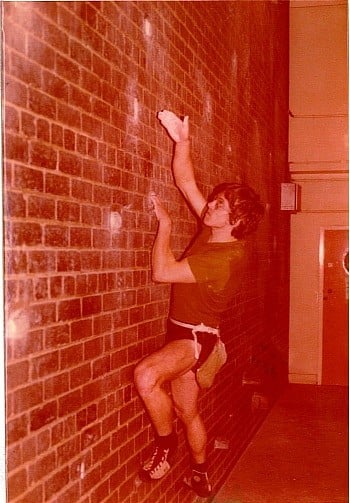

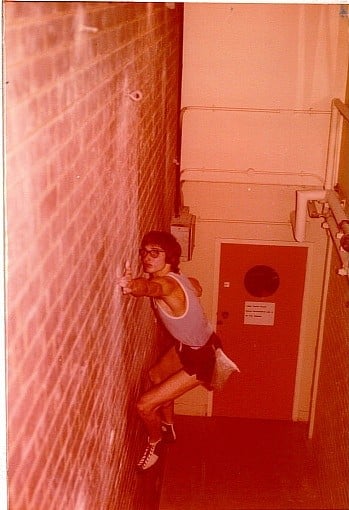

Unbeknown to me however, in 1964 an educationist named Don Robinson had built a climbing wall in a corridor in Leeds University. Until recently, Don Robinson was little more than a long-familiar name to me. However Jonathan Pitches, Professor of Theatre and Performance at Leeds University, has interviewed him as part of the Performing Landscapes: Mountains project. Reading the transcript, it's clear that Robinson is a polymath, able to flick from abstract thought to the most practical of considerations with enviable ease. Above all, he is a man who wants to help others. And he specifically designed the Leeds wall as a 'teaching machine' which climbers could use for self-learning.

The wall… which begat all walls

The original wall, which was later extended with artificial panels, consisted of pieces of stone cemented into the brickwork. By modern standards, it was primitive. But Robinson was using the best technology available at the time. And, unlike modern walls where you can relatively easily re-set (and fine-tune) routes/problems, Robinson's creation was literally set in stone. It had to be right first time. And it was. One instance of Robinson's finesse was the trio of 'stepping stones' at the right-hand end of the wall. They gave the most exquisite balance moves imaginable. If those stones had stuck out just a little more, the moves would have been pointlessly easy; if they'd stuck out just a little less, the moves would have been downright impossible. Robinson worked with tight tolerances, with a technology which had to be right first time and created a charming sequence which I recall with affection nearly fifty years later.

In 1968 a young man named John Syrett arrived to study Applied Mineral Sciences at Leeds University. Coming out of an adjacent room after judo practice, he met Don Robinson and was persuaded to try his hand at the wall. Syrett proved a natural; judo fell by the wayside. He began to spend more and more time at the wall. What he was doing was what we'd now term bouldering. Once you link a series of moves, inevitably you think, 'Can I do it with one or two or three less holds?' Curiosity lures you into ever-harder sequences.

John Syrett was creating a new paradigm

It's probably safe to suggest than no-one (not even himself) realised that John Syrett was creating a new paradigm. While a few people, principally in the Peak district, started climbing on local outcrops, most began, as I did, in the mountains. Whether outcrop or mountain crag, everybody started on real rock – with, back then, a distinct lack of protection. And, of course, lack of protection inhibited most people pushing their grades.

Conversely John Syrett could push his grade for hour after hour, every day, in relative safety. In recent years, Malcolm Gladwell has popularised the 10,000 hours principle whereby world-class performers seem to have accumulated around this amount of time not just practising their art but focusing hard on improvement. By 1970, just two years after he'd started, Syrett had accumulated perhaps 1,000 hours of focused improvement (bouldering ever harder). Now, in absolute terms, obviously this guesstimate of 1,000 hours is a long way short of Gladwell's 10,000. But, in relative terms, this 1,000 or so hours probably put him massively ahead of almost any other climber in the world apart from John Gill.

When John Syrett ventured outside, he transitioned in the most spectacular manner imaginable

Over the intervening half-century, the climbing world has seen innumerable 'wall warriors', who excel inside yet flounder dismally on real rock. The key principle is transition: how do we adapt core skills to a subtly different and usually far more challenging environment? When John Syrett ventured outside, he transitioned in the most spectacular manner imaginable.

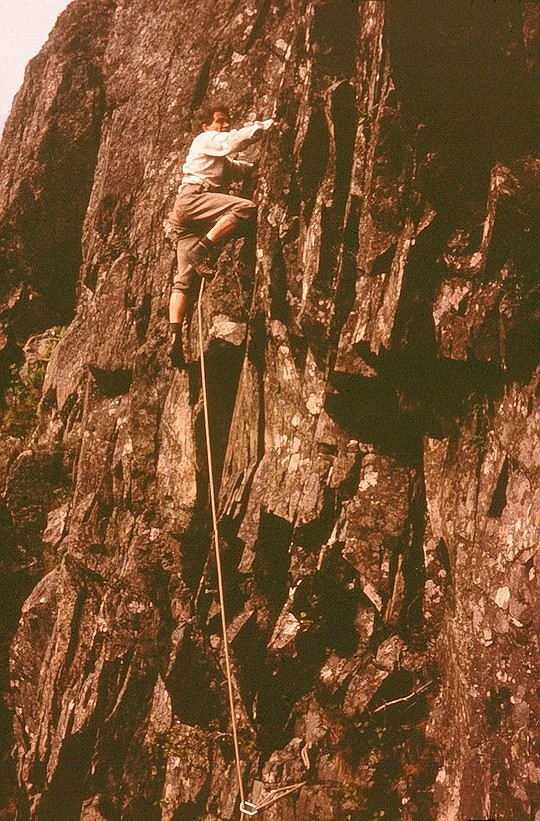

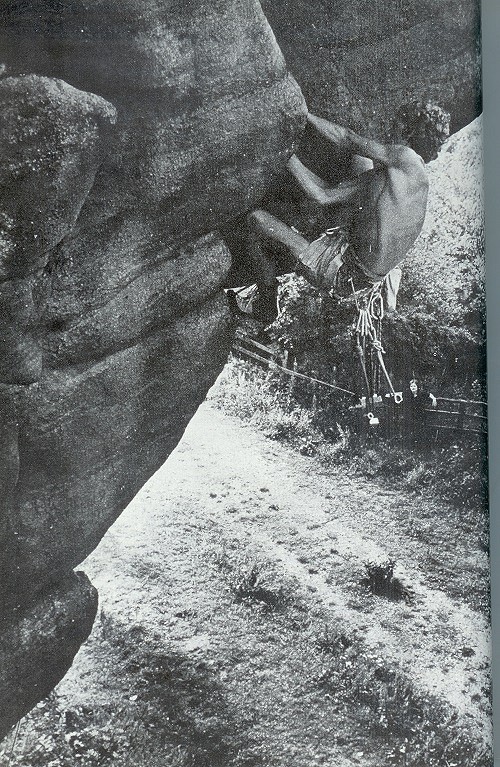

Almscliff crag is Yorkshire's most famous gritstone outcrop. The North West Face is its most impressive aspect. The most intimidating part of the North West Face is what the late Paul Williams dubbed 'the Great Wall of grit' – the aptly named Wall of Horrors. Wall of Horrors occupies a legendary place in the history of British climbing. Although Arthur Dolphin top-roped it in the 1940s (futuristic or what?), it had to wait until 1961 for its first ascent. Allan Austin employed combined tactics to overcome the V4 start. However his inspired solo of the remainder of the route was outrageously bold. Wall of Horrors was arguably harder and more serious than any Brown or Whillans route. The White Rose had been laid on gritstone for all to see.

A chop route – of mythical proportions

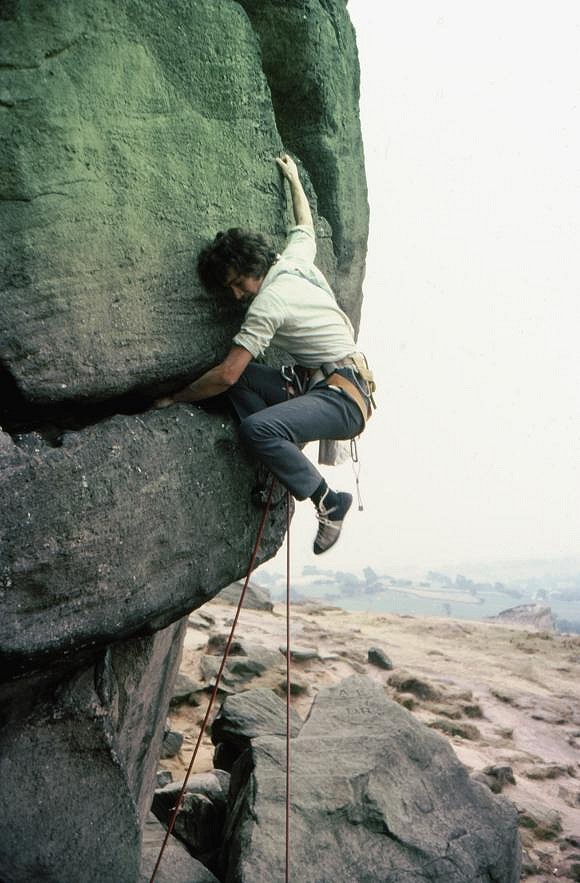

Throughout the 1960s the reputation of Wall of Horrors as a 'chop route' grew to mythical proportions. As it happened, Tony Nicholls made the second ascent in 1964; however few people outside the tightly-knit world of Lancashire climbing knew of his feat. By 1970 a repeat of Wall of Horrors must have seemed by far the greatest prize on grit. John Syrett duly obliged on a windy November day. His friend and climbing partner, John Stainforth, took one of the most iconic ever British climbing photographs. The legend of Wall of Horrors was supplanted by the legend of John Syrett. The climbing world reeled. How had somebody gone from rank beginner to repeating arguably the hardest route in the country in only two years? There seemed a three word answer: the Leeds wall. The Leeds wall swiftly saw hordes of aspirants hoping that some of the magic might rub off on them too. Over the following decade, its alumni read like a 'Who's Who' of British rock climbing: Al Manson, Pete Kitson, Mike Hammill, Steve Bancroft, Chris Addy, Chris Hamper, Pete Gomersall, Martin Berzins, Rob Gawthorpe, Tony Mitchell. The list goes on and on. It also included two figures who would revolutionise climbing – Pete Livesey and his erstwhile protégé, Ron Fawcett.

John Syrett had demonstrated the superiority of climbing wall training over bumbling around in the mountains, the 'on the job' learning practised by me and so many others. In four years, I'd gone from beginner to VS; in two years, he'd gone from beginner to E3. (And, back then, the difference between VS and E3 was more like the difference between E2 and E8 today.)

But what about someone who wasn't particularly talented?

Wouldn't they be the acid test…

Critics might argue that John Syrett was talented: a natural, with enviable suppleness. He was talented – no possible doubt of that. But what about someone who wasn't particularly talented? Wouldn't they be the acid test?

Pete Livesey had been an outstanding runner, an outstanding kayaker, an outstanding caver and an outstanding climber. In each case however, he'd been held back from being the absolute best by lack of talent. Pete took a long, hard look at climbing and realised that, compared to conventional sports, the athletic curve was still pathetically low. The best climbers of the 1960s smoked, drank, exercised sporadically and rarely managed to climb much rock in winter. Conversely Don Robinson's Leeds wall, as used by John Syrett, was a venue for year-long dedicated improvement.

Climbing had moved on – from the E2/E3 of the Brown/Whillans/Crew era to a stunning E5

Pete knew that the routes he wanted to do would be different to any which had existed previously. Instead of just a few hard moves (typical of grit), they would have hard move after hard move after hard move (typical of limestone). So he practised long finger-stamina traverses (one of my original ideas!) firstly at a wall at Scunthorpe, then at Leeds, then at the other local walls which were springing up, such as those at the Rothwell and Richard Dunn sports centres. Now Pete may have lacked climbing ability per se – but he had other, extremely powerful strengths. He was mega-competitive, had an unrelenting work ethic, possessed a keen analytic mind and had a wealth of relevant sports/outdoor pursuits experience to draw upon. Certainly he didn't have problems of transition. As another of his protégés, Pete Gomersall, astutely pointed out, "Pete may only have been able to do [British] 6b. But he could do it thirty feet up, with no protection, as easily as he could do it at ground level. And few people can manage that."

Pete's 1960s routes at the lethally loose Langcliffe Quarry had vividly demonstrated his boldness. Subsequent additions, such as the FFA of Face Route and the FA of Jenny Wren, both at Gordale, hinted at what was to come. In 1974 he did the FAs of Right Wall in Wales and Footless Crow in the Lakes. Both attained the kind of legendary status that Wall of Horrors had done previously. It was obvious that climbing had moved on – from the E2/E3 of the Brown/Whillans/Crew era to a stunning E5.

The athletic curve, which Pete Livesey saw so clearly, went ballistic

Climbing walls meant that you could train for improvement all year round. The introduction of decent wires in the early 1970s and the first commercially available camming devices in the late 1970s meant that many hitherto unprotectable routes could be tamed. E5 went up to E6, then E7 at the end of the decade. The early 1980s saw the introduction of E8, then E9 (Indian Face). They also saw the split into trad and sport. F7a quickly became F8a, then F8b, then F8c. The early 1990s saw Hubble and Action Directe, the first F9as in the world. The last decade of the 20th century saw the mass acceptance of bouldering as a discipline in its own right. This not only pushed up bouldering standards; it also helped to push up standards in both sport and trad. Now we're looking at numbers such as E11, F9c and f9A. The athletic curve, which Pete Livesey saw so clearly, went ballistic.

And yet I'd argue that the focal point upon which everything pivoted was the original Leeds university wall created by Don Robinson and popularised by John Syrett. I'd argue that you can trace most of the significant developments in rock climbing over the last forty years back to that Leeds wall.

Let's take some current limits of rock climbing: the first f9A, the first F9c, the first F9a onsight, the first and second free ascents of the Dawn Wall, the first solo of Freerider. As far as I know, all six protagonists firstly got good on plastic, indoors, then transitioned to world-class performances.

Over half a century after the original Leeds wall was built, there are untold thousands of indoor climbing walls all over the world. Every day, millions of people use them. Every year, hundreds of thousands of people come into climbing, not from hillwalking but from climbing walls. This represents a huge structural change to the climbing community.

One wall, one climber and one route…

And yet how many climbing wall users know that the very existence of their wall and the popularity of walls generally came from one wall, one climber and one route?

Climbing owes a profound debt to Don Robinson and John Syrett. Between them, they changed climbing history

With his company, DR Climbing Walls Ltd, Don Robinson went on to build over 400 more climbing walls – yet another reason for us to be in his debt. John Syrett wasn't so fortunate. His severed tendons and his sadly untimely death are well-known. He occupies an iconic status in the climbing world, comparable perhaps to that of Nick Drake in music. It's probable that, towards the end, he felt his life was a failure. But I'd argue, very strongly indeed, that it was anything but a failure. With his use of the Leeds wall as an instrument of climbing development, John Syrett replaced the old 'work through the grades' model that I and everyone else – from the 1890s to the 1960s - had been brought up on. 'Work through the grades' doesn't address what I'd now term 'critical processes' (such as surgically precise footwork, and shakeouts within moves) which you need to get better. 'Work through the grades' makes no mention of a safe environment where you can learn. 'Work through the grades' ignores the crucial importance of learning from failure, of embracing failure, of 'failing forward' to eventual success. For that, of course, you need a safe learning environment. And then you need to leave that safe environment, to transition into the 'real world', the operating environment, as John Syrett so notably did on Wall of Horrors.

John Syrett was almost fifty years ahead of his time

He was anticipating modern bouldering. He was showing us what was possible

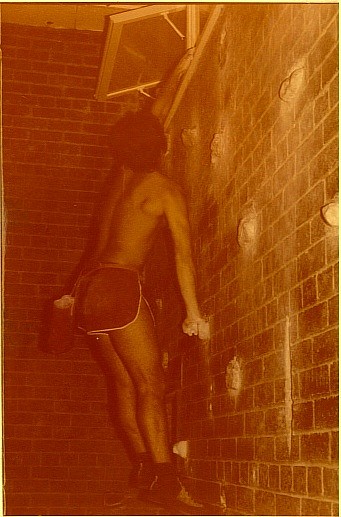

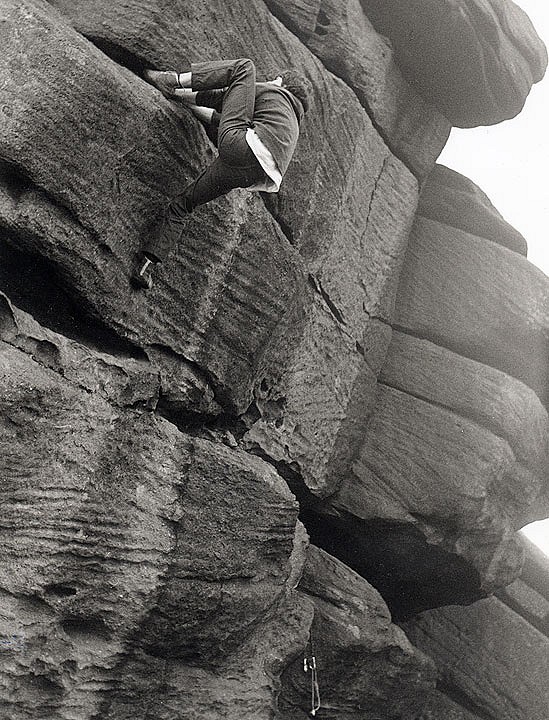

And there's another reason why John Syrett is such a pivotal part of climbing history. Apart from Johnny Dawes, he was the most creative climber I've ever seen. When I saw him climb, I had absolutely no idea what he'd do next. (Did he know?) The use of volumes has revolutionised modern bouldering indoors, made it three-dimensional. Contemporary success demands pronounced suppleness, gymnastic ability and inspired creativity – all of which John Syrett had in abundance. Look at the photo of him on the FA of Joker's Wall, with his foot locked at head-height. Look at the photo of him on the FA of Encore, heel-hooking. Look at him in the frog position on the crux of Wall of Horrors. These body positions are stunningly atypical of climbers operating circa 1970. Conversely, they're exactly what you'd expect of contemporary boulderers. John Syrett was almost fifty years ahead of his time. He was anticipating modern bouldering. He was showing us what was possible.

How to get good - at anything

I'd argue that to get really good at climbing - at anything - you need to follow a sequence broadly similar to this:

- Learn the basic skills.

- Isolate and address the critical processes (what really matters, the 'skills within skills').

- Learn in a relatively safe environment (both physical and psychological).

- Embrace failure. Learn from failure. 'Fail forward' to success.

- Master the critical processes.

- Transition effectively into the operating environment.

- Continue purposefully monitoring, reviewing and learning. Develop feedback loops. Adopt a mindset of lifelong learning.

Changing climbing history

Between them, Don Robinson and John Syrett gave us the basis for this model of improvement in climbing, so much more powerful than the essentially passive one which had existed previously. Between them, they created the impetus for a world-wide climbing wall industry. Between them, they changed climbing history.

Virtually all of us owe them a debt which we can never repay. This article is my attempt, however inadequate, to repay my debt to them.

- FEATURE: The Corridor: A Review 14 Apr

- ARTICLE: Allan Austin Obituary – A Prophet of Purism 9 Jan

- IN FOCUS: Will Perrin - A Child of Light 14 May, 2024

- IN FOCUS: Custodians of the Stone 5 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: Clean Climbing: The Strength to Dream 31 Oct, 2022

- ARTICLE: Thou Shalt Not Wreck the Place: Climbing, Ecology and Renewal 27 Sep, 2022

- ARTICLE: John Appleby - A Tribute 28 Mar, 2022

- ARTICLE: We Can't Leave Them - Climbing and Humanity 9 Feb, 2022

- ARTICLE: Staying Alive! Climbing and Risk 9 Jun, 2021

- FEATURE: The Stone Children - Cutting Edge Climbing in the 1970s 14 Jan, 2021

Comments

That was a great read Mick; thanks for taking the time to write it.

Thanks Mick, a nicely told tale where I knew the plot but not all the details. Like you I devoured the climbing/mountaineering section of my local library & have vague memories of a book about climbing walls, maybe by Don Robinson and I guess published in the early 70s - any one else remember such a book ? Maybe Google will find it.

edit - seems the book I remembered wasn't by Don - 'Artificial climbing walls' ? by Kim Meldrum and Brian Royle published 1970

Lovely article, Mick. It was certainly a trip back down memory lane.

I remember many trips to the Leeds Wall back in the mists of time. Countless laps of the traverse did wonders for finger strength and stamina, but I was never able to summon up the courage for Syrett's Roof :-)

Nice one Mick and yet another great read! :-) Cheers Dave