Mick Ward remembers the key players in the climbing scene and major British ascents of the 1970s...

In 1972 Tony Willmott died, soloing in the Avon Gorge. To his friend, Al Baker, he was a stone child. His climbing shoes went to a young Londoner named Stevie Haston. Stevie and many others followed Tony Willmott's inspiration. Climbing standards soared; nothing would ever be the same again.

In climbing as in much else Lancashire always seems to have been the poor relation to Yorkshire. Nevertheless over the years it has boasted a notable stable of dark horses. Some of these dark horses have been among the best climbers in the country.

In the early 1950s Arthur Dolphin successfully top-roped Wall of Horrors (E3), arguably harder than any Brown or Whillans route. He intended to lead it, but sadly died in the Alps before he could try. In 1960 Allan Austin soloed the first ascent: a tour de force. Wall of Horrors rightly became the jewel in the crown of Yorkshire climbing.

In 1964 Lancashire dark horse, Tony Nicholls, made the second ascent of Wall of Horrors. There was no fuss or fanfare. In 1967 another Lancashire dark horse, Ray Evans, made the first ground-up attempt on what would, in 1986, become Indian Face, Britain's first E9. There was no fuss or fanfare. In 1970 Lancashire dark horse Hank Pasquill made the first ascent of Silly Arête (E3) at Tremadog. There was no fuss or fanfare. The wonderfully named Silly Arête was among the hardest routes in Wales at the time.

In both cases, fame arrived courtesy of a burgeoning climbing media

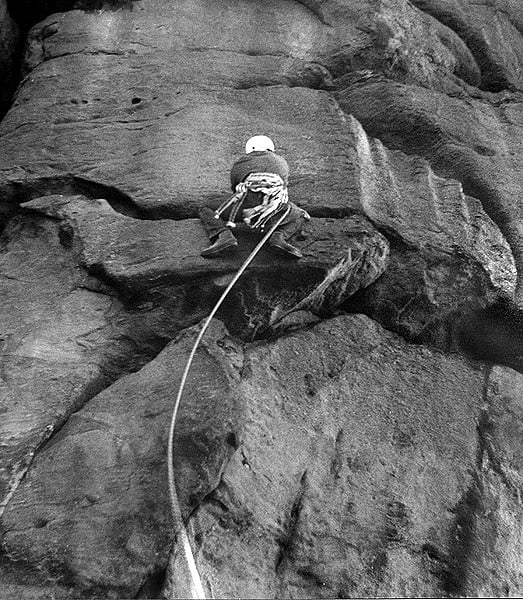

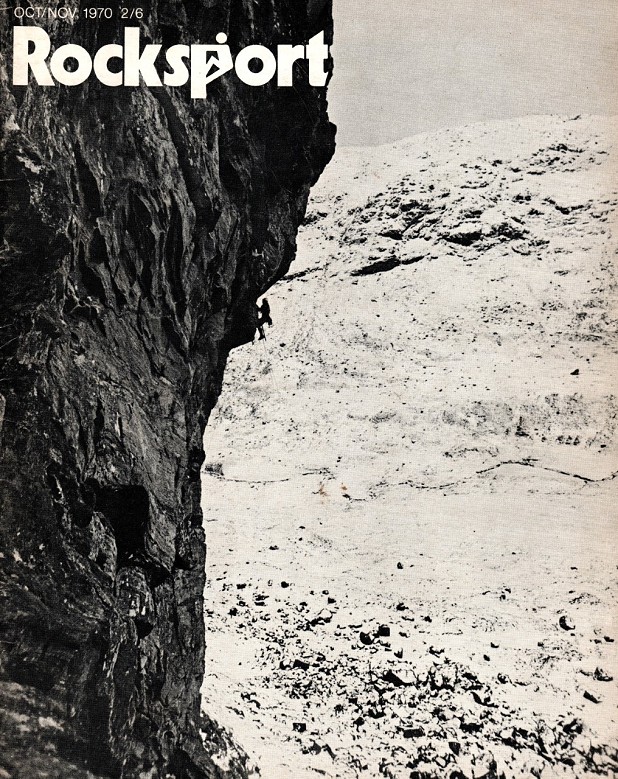

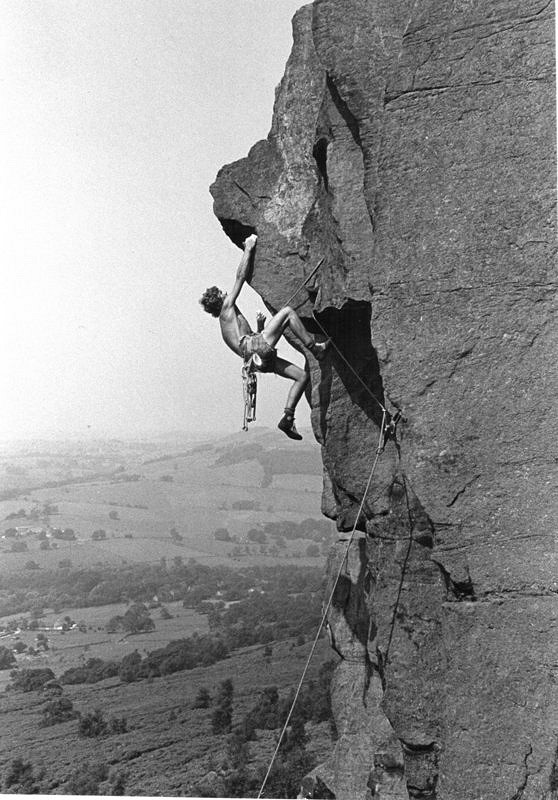

Lancashire dark horses may have mused upon the unfairness of life when John Syrett became famous for making the third ascent of Wall of Horrors in 1970. They may have mused upon the unfairness of life when Syrett's contemporary, Al Rouse, became famous for soloing The Boldest, the most feared route in Wales, at around the same time. In both cases, fame arrived courtesy of a burgeoning climbing media. John Stainforth's brilliant photograph of John Syrett poised on the crux of Wall of Horrors was first published in Rocksport. Some 50 years later, it remains one of the most iconic images of British climbing.

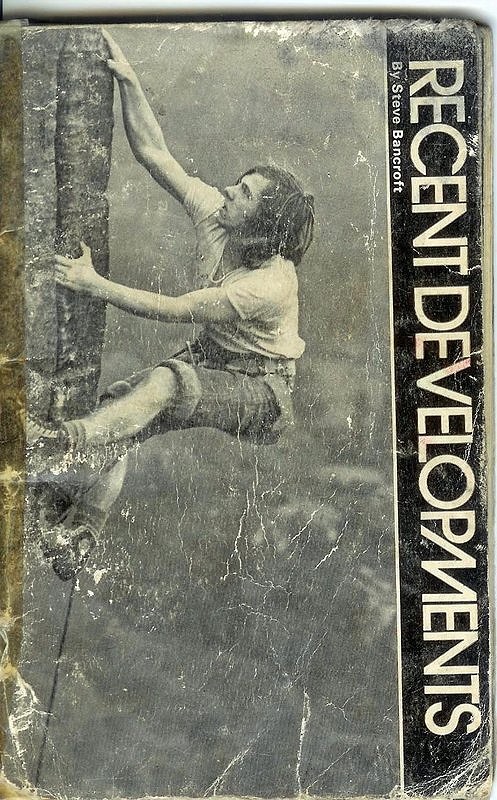

Syrett's astonishing rise from beginner to top climber focused attention on training in general and the Leeds wall in particular. Aspirants flocked to the wall; it became the forcing ground for harder and harder moves. Syrett and his contemporaries Al Manson and Pete Kitson took the increased standards outside to their local Yorkshire outcrops. One last great problem was the Goblin's Eyes roof at Almscliff, failed on by Syrett, top-roped by Rouse and led by Pasquill as Orchrist (E5). Orchrist made use of a cunning siderunner, artfully conceived by a youthful acolyte named Steve Bancroft. More of him later.

While attention was focused on the Leeds wall, a lonely figure was doing lap after lap after lap at another indoor wall in deeply unfashionable Scunthorpe. Pete Livesey had been a top runner, a top kayaker and a top caver. He'd made an early ascent of Vector and his 1960s first ascents at Langcliffe had demonstrated an enviable boldness. In running, kayaking and caving, he'd been prevented from being the absolute best by lack of natural talent. Pete looked at climbing more carefully, saw an athletic curve just beginning to take off, knew the time was ripe for him to make his move.

A sea change in British climbing

Advances on gritstone were coming about through the superb technicality of climbers such as Syrett, Manson and Kitson. Limestone was more about endurance. Endless laps on walls might be boring as hell but they gave you superb endurance. Pete took his endurance outside with FFAs of Face Route (E3) and Rebel (E5) at Gordale and FAs of Jenny Wren (E5) at Gordale and Central Wall (E4) at Kilnsey. These were big routes for the day. Unfortunately they attracted considerable criticism from the climbing establishment. In general, clubs such as The Climbers' Club, the Fell and Rock and the Yorkshire Mountaineering Club (YMC) controlled guidebook production. If they didn't approve of your routes, then it was highly unlikely that aforesaid routes would see the light of day in a guidebook. The YMC had little faith in the reliability of Pete's reporting. In particular, his free ascent of Face Route was doubted. At around the same time, a talented young Lakes climber named Rob Matheson made an outstanding first ascent of Paladin (E3) on White Ghyll. It too attracted criticism from the guidebook writers.

If the YMC wouldn't publish Pete's FAs and FFAs (and the number quickly grew!) his riposte was to publish them himself. A little guidebook, modestly entitled 'Lime Climbs' duly appeared. There was historical precedence; in the mid-1960s the then Ed Ward-Drummond had produced a similar guidebook, the more grandiosely entitled, 'Extremely Severe in the Avon Gorge'. (Slightly earlier there had been shock and outrage when Paul Ross and Dave Thompson produced the first 'pirate' (i.e. non-club) guidebook to Borrowdale. How times change!)

In today's money, your XS of choice might be E1, E2 or E3

In the early 1970s, the top grade was pretty much XS (Extremely Severe). Higher grades – awarded to a few select horrors – never really caught on. The cognoscenti were well aware that the XS grade was severely overloaded. In today's money, your XS of choice might be E1, E2 or E3. (If you were really unlucky, it might be even harder, e.g. Our Father E4). You took your chances. Fair enough. But what wasn't fair enough were Yorkshire routes such as Wombat, Carnage and The Macabre, which were blatantly graded HVS. Those capable of doing them knew full well that they were comparable with the harder Welsh Extremes. When John Stainforth attempted to remonstrate with the YMC guidebook committee, he met the same fate as Pete Livesey and Rob Matheson: he was slapped down. Power was concentrated in very few hands indeed. Some of the people running things in Yorkshire were also running them in the Lakes – particularly Langdale.

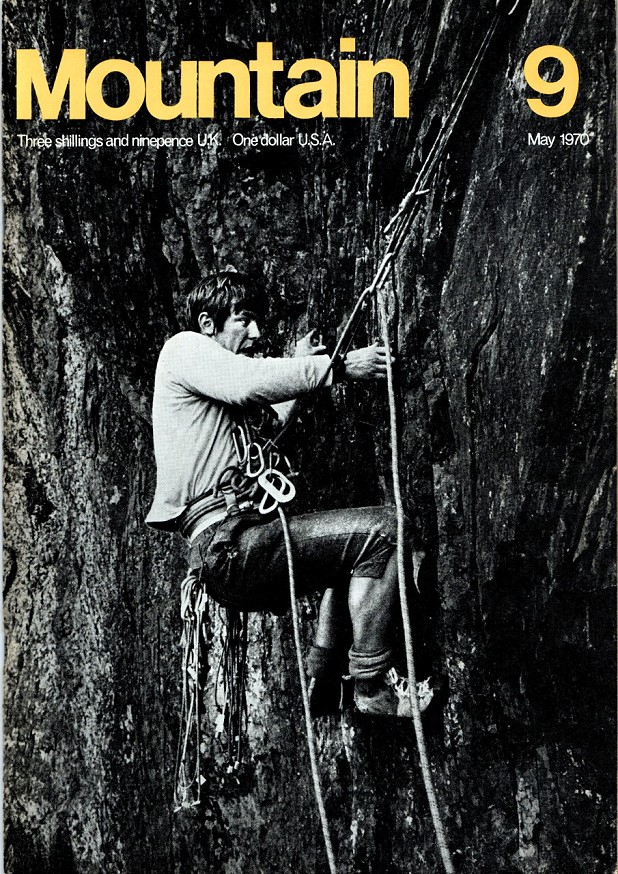

In 1973 top US climber 'Hot Henry' Barber visited the UK. He'd culled a shopping list of hard routes from British magazines such as Mountain. Besides visiting unfashionable venues such as Lliwedd to learn about the history of British climbing, he also went though his shopping list. His conclusion was that cutting-edge climbing standards were roughly comparable in the US and in the UK. In both cases, they were rising sharply. Did Barber know what he was talking about? Well, in 1975 he brought 5.12b to Yosemite with the FA of Fish Crack, so I'd suggest that, yes indeed, he did know what he was talking about.

Pete's domination seemed total...

In 1974 Pete Livesey made the first ascents of Right Wall (E5) and Footless Crow (E5). Right Wall was the hardest route in Wales and Footless Crow was the hardest route in the Lakes. At Ilkley he freed the impossible looking Wellington Crack (E4) and at Tremadog he freed the unlikely looking Zukator (E4), one of the few routes on which Barber had failed. His dominion seemed total.

Yet however total Pete's dominion, he was very much aware that there was no shortage of competition. He only had to turn up at a climbing wall for a horde of spotty, anorexic youths to try to burn him off. In the 1970s virtually everybody wanted to be the best at climbing. We were all so young – there was far too much testosterone flying around! From the beginning of the decade, in Sheffield, a lad named John Allen, barely in his teens, was being systematically trained up to be the best climber ever. Instead of wasting time on Severes, he was top-roping classic Extremes from an early age. Soon he went from top-roping them to leading them and then soloing them. He became friends with Steve Bancroft and the pair morphed into the most successful climbing partnership since Brown and Whillans. At Stanage, Old Friends (E4) took the big wall right of Neb Buttress. As had happened with Syrett and Rouse, Allen became instantly famous in 1975 when he did the FFA of Great Wall (E4) on Cloggy. This was something which had defeated several strong contenders, including leading American climber Steve Wunsch. Ironically it appears that Yorkshire's Iain Edwards may have beaten him to the coveted first free ascent but never bothered to claim it. (If only Iain had lived just across the county line, we could put him down as yet another Lancashire dark horse!)

The gods of grit

On grit, Allen produced two stylish masterpieces, Curbar's Prophet of Doom (E4) and Stanage's Nectar (E4). Both take stunning groove lines and, for many, both will feel very hard indeed for E4. The mid-70s heralded a gritstone revolution. A plethora of outstanding lines were climbed by those with the vision to tackle them. Jim Perrin wrote wryly, 'What blind eyes did we cast over Cratcliffe?' where dozens of climbers could have made the first ascents of classics such as Boot Hill (E3), Tom Thumb (E2), Fern Hill (E2) and Five Finger Exercise (E2). At Millstone and Lawrencefield virtually all the old aid lines were freed. The hardest came from John Allen with the magnificent London Wall (E5), eclipsing Livesey's Wellington Crack in difficulty.

Could standards go any higher? In the mid-60s, Ed Drummond had established a superb canon of new routes in the Avon Gorge. He'd gone on to produce Welsh classics such as The Strand (E2), T Rex (E3) and Great Arete (E4). In the '70s, he reinvented himself once again with Stanage classics such as Archangel (E3), Wuthering (E2) and Asp (E3). A teacher at Allen's school, he was beaten to the first ascent of White Wand (E5) by the young pupil.

In 1973 Drummond climbed arguably his greatest and certainly his most controversial route on gritstone. Linden takes the huge, seemingly blank wall right of Right Eliminate. Drummond chipped at least two small holes in the rock for skyhooks, for which he was excoriated in Mountain magazine by another leading activist, Keith Myhill. Drummond's riposte was that it was 'free climbing with skyhooks' and not aid climbing, per se. Previous linguistic gems had included, 'Stand on the peg without using it for aid' and the immortal, "I slipped - I didn't fall!" For someone who'd studied philosophy, Drummond could be surprisingly heedless of logic.

In 1976 Londoner Mick Fowler repeated Linden without skyhooks, to produce an E6 on grit. In the early 1980s, Linden received an astonishing onsight by Merseyside climber, Phil Davidson. Ethics aside, Drummond had produced a masterpiece – and one which was deadly serious. A fall from the top wall would most probably prove fatal. It's rumoured that a solo ascent from Pete Livesey, no stranger to bold climbing, left him severely shaken.

A brilliantly simple solution to grading

We all knew that the XS grade was severely overloaded... How could Cenotaph Corner and its neighbour, Right Wall, be of comparable difficulty? The answer was simple - they weren't. A short-lived solution was to have Mild XS, XS and Hard XS. But this didn't really work either. It was obvious that there were more than three grades for which to account. And standards were constantly going up, with even harder grades a distinct probability. Lakes climber Pete Botterill devised a brilliantly simple solution. Why not divide the old XS grade into an open-ended system of E grades, initially from E1 to E5? Cenotaph would be E1 and Right Wall would be E5. As the system was open-ended, when a clearly significantly harder route was done, it would merit an even higher grade, e.g. Linden, at E6.

Linden was joined by Fawcett's Slip n' Slide at Crookrise, Livesey's Zero on Suicide Wall and his chillingly named Mossdale Trip at Gordale. Jerry Peel contributed the horrific offwidth of Giggling Crack at Brimham. All these routes merited E6. Even Steve Bancroft popped up to give us the no doubt aptly named Narcissus at Froggatt. Again it was E6.

To a 1960s climber, 5c was bloody hard and 6a pretty much the living end. But, by the mid- 1970s, a new technical grade was emerging – 6b. And 6c already existed, e.g. Giggling Crack. Clearly Right Wall (E5 6a) was deemed to be harder overall than Nectar (E4 6b). But different climbers might have different preferences. Someone with psyche and endurance might run up Right Wall yet grind to a halt on the puzzling crux of Nectar where suppleness pays distinct dividends. Conversely someone who could stem to glory on Nectar might run out of steam on Right Wall.

Making qualitative sense of it all

In a highly interesting essay, Pete Livesey aimed to make qualitative sense of it all. Grades aside, he identified three types of hard routes, epitomised by Nectar, London Wall and Linden. Nectar (E4 6b) was well protected but technically very hard indeed – very much one for the boulderers. London Wall (E5 6a) was well protected but desperately sustained – requiring endurance as well as expertise on finger cracks. Linden (E6 6b) had a hard crux, followed by easier but incredibly bold climbing. Put another way: with Nectar you could be stopped by lack of technical ability (or suppleness). With London Wall, you could be stopped by lack of fitness. With Linden, you might be stopped by lack of boldness. The ideal climber was one with technical ability, supreme fitness and - most prized of all - boldness.

It's interesting to compare top 1960s climbers with top 1970s ones. I'd argue that both were very bold indeed. But several factors combined to enable 1970s stars to climb so much harder than their '60s counterparts. Bouldering - on walls and outside - gave increased technical ability. Traversing on walls gave far greater fitness. The introduction of decent wires (early '70s) and the first generation of cams (late '70s) started to give reasonable protection for the first time in climbing history. So, in general, bold routes tended to become somewhat less bold than before – though still pretty bold!

When it came to new routes however, there was yet another factor...

When it came to new routes however, there was yet another factor. Until the 1970s, rock climbing in the UK was viewed as a subset of mountaineering. Thus the ground-up ethic prevailed with new routing. Limestone still enjoyed an evil reputation because limestone generally requires cleaning and cleaning en route (particularly on a first ascent) is apt to be decidedly exciting. Ground-up cleaning on hard routes tends to force you into using aid which you mightn't otherwise need. A route might be written up with a point or two of aid. Has the aid been needed for cleaning, resting or progress? How could you tell? (Often you couldn't.)

A generation of rock athletes was swiftly emerging for whom aid – any aid, for any reason – was anathema. One solution was to abseil prospective new lines, assess feasibility and clean as required. Of course invariably you tended to check out crux moves while you were at it. And, if the route was particularly scary, well why not top-rope it too?

To us, today, more than 40 years later, all of this is pretty standard. In the 1970s it wasn't. Top-roping was still widely viewed as a crime. A dichotomy emerged between climbing a new line ground-up as engagement with the experience and operating top-down to produce a 'more professional' product. To some people, messing around on 6a or 6b moves on loose, uncleaned rock was ineffective at best and downright silly at worst. Crucially it meant that a second ascensionist lacked knowledge of the route which had been enjoyed by the first ascensionist. Staunch traditionalists (i.e. bitter old men) could mutter darkly that the stunning breakthroughs in climbing had only been achieved by better protection (cheating) training (more cheating) and dodgy tactics (yet more cheating). And when it came to chalk, well...

The ideal climber

The ideal climber was one with technical ability, supreme fitness and - most prized of all - boldness... Enter a young Yorkshireman named Ron Fawcett. Back in 1971 I'd met Boggie (John Bogg) and Shagger (Paul Trower) in the Pass. About the only thing on which they'd agreed was that this young lad whom they'd recently taken out climbing was going to be the next big thing. "Is he really that good?" I queried dubiously. As one, they replied, "Yes, he bloody well is!"

In the early 1970s Yorkshire became a forcing ground for standards. Broadly speaking, there were two camps. The Leeds trio of John Syrett, Al Manson and Pete Kitson particularly revered grit – and local grit at that. Conversely Pete Livesey and his protégé, Ron Fawcett, were more focused on limestone and mountain routes. Yes, of course there was overlap but, generally speaking, the first group was focusing on bouldery routes whereas the second was focusing on endurance routes.

Whillans had followed in Brown's wake, with the second ascent of Cenotaph Corner and a shared first ascent of Cemetery Gates, before emerging in his own right. Similarly Fawcett made the second ascents of Right Wall and Footless Crow before emerging in his own right. As Livesey mischievously noted, "I always knew Ron was better than me; the trick was not to let him realise it!"

It's a timeworn principle of climbing that the young protégé outstrips the older mentor. And this is exactly what happened with Livesey and Fawcett. From 1976 until the end of the decade, Fawcett dominated British climbing. Pete had shown the way; he'd left a legacy of great routes all over the place. But Big Ron, quiet and unassuming on the ground yet possessed of fearsome ability on rock, was emerging as a quintessential sporting hero. After Joe Brown, he is probably the most respected of all British climbers.

The golden summer of '76

1975 was a notably hot summer; 1976 was even hotter. Mountain crags came into condition for months on end. It was a re-run of the famous summer of 1959. As with '59, suddenly there were more people than ever before doing hard routes. Endless good weather, improved training, better gear... The late '60s doldrum was over; there was a definite feelgood factor in British rock climbing.

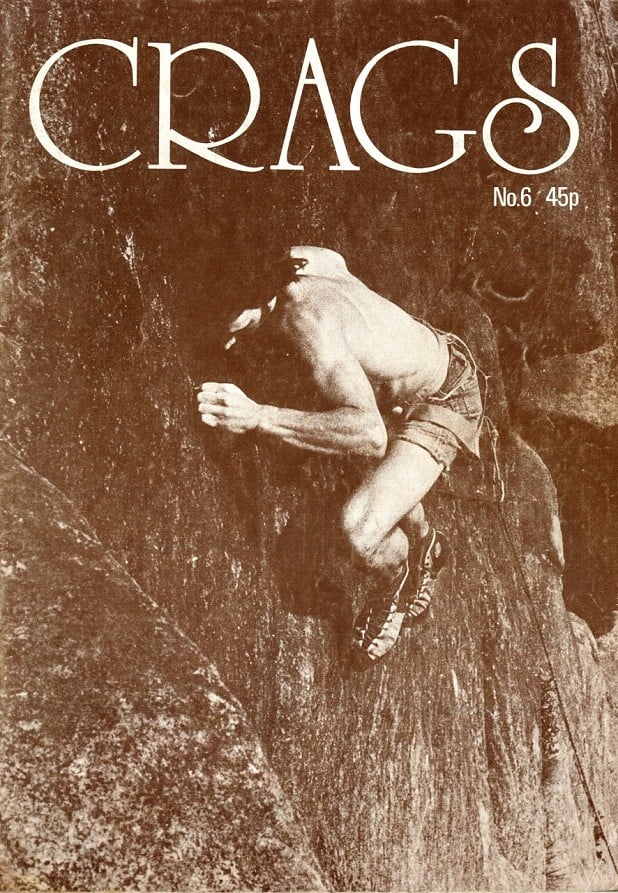

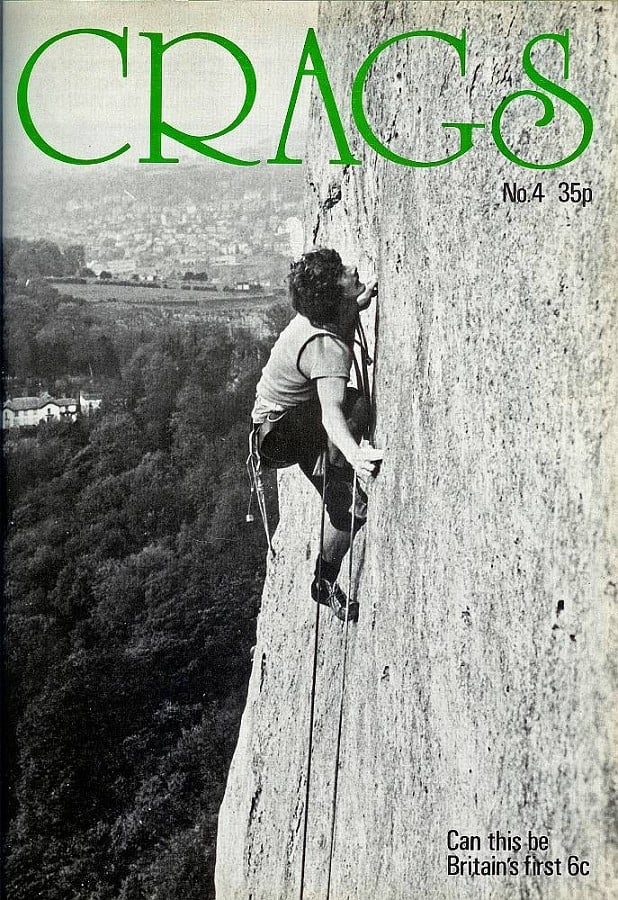

After such a promising beginning in the late 1960s, Rocksport, the magazine dedicated to covering the UK climbing scene, had spluttered to a halt in the early-70s. Suddenly a new magazine, Crags, burst onto the scene. The timing was impeccable. A hero was needed – a symbol of the zeitgeist. Ron Fawcett became that hero. By 1976 he was undoubtedly the best climber in Britain. The front cover of Crags 4 had an iconic shot of him on the first ascent of Supersonic (E4). Al Evans took the photo while Geoff Birtles provided arguably the best caption ever: 'Can this be Britain's first 6c'. I would imagine that Fawcett, as with Brown before him, found the publicity rather embarrassing. Certainly when you met him out soloing on grit, he remained accessible, friendly and encouraging to those of us (i.e. all of us!) with far lesser ability. It didn't matter even if someone was struggling helplessly on a V Diff. They'd still get a sympathetic grin and a friendly word of encouragement.

By the late 1970s, British climbing had changed dramatically

'Yond Cassius has a lean and hungry look,

He thinks too much; such men are dangerous.' (Shakespeare)

By the late 1970s, British climbing had changed dramatically. Yes, people still went to the Alps but it was becoming accepted that, if you wanted to remain a pure rock climber, this was fine. Rock climbing wasn't simply training for mountaineering; it was a valid entity in its own right. However, despite dedicated devotees such as Al Manson, bouldering was still generally viewed as training for cragging. When Al chose to spend his two weeks' holiday in Fontainebleau rather than Chamonix, we were aghast. Surely this was art for art's sake? And, in a way, it was. Aptly it would take until 1984 for the dawning realisation that bouldering was the way to gain power. Al was a man well ahead of his time.

Again, with seemingly impeccable timing, a new venue arrived. Why go to Chamonix and spend two weeks sitting in a tent in the pissing rain when you could visit the Verdon Gorge? Today people regard the Verdon as a pretty scary place. But the 1970s generation of Brits had served their apprenticeships on scary crags. The Verdon was just a lot bigger. Crucially for the development of international climbing, the French could see how accomplished climbers such as Livesey and Fawcett were. While the French had superb technique, honed by many years of bouldering at Font, for generations rock climbing in France had been hampered by the Alpine insistence on speed. 'Tire clous' meant that you pulled on gear, whether threads, pegs or bolts, to get up the route faster. While this made sense on the Eiger, it made less sense in the Verdon and far less sense on smaller crags. Jean-Claude Droyer emerged as a kind of French Livesey, freeing routes where he could. Patrick Berhault and Patrick Edlinger would take things much further. The glory days of French rock climbing hadn't quite arrived. But when they did, standards would leap more quickly than at any other time in history.

In the latter part of the 1970s, E5 became almost commonplace. It was rumoured that, at one point, humble Carlisle had more E5 leaders than anywhere else in the country. E6 became the new E5. And there were outliers, such as Andy Hall's The Aardvark and the Ferret (E7) at Avon. But The Aardvark and the Ferret wasn't really accepted at the time. It's an eliminate and allegedly it was (sensibly) repeatedly top-roped before the FA. The two bolts on Fawcett's The Cad (E6) were only accepted because it was Big Ron. Bolts on a Welsh sea-cliff were no more welcome in 1978 than they had been in 1963 when Pete Crew had placed one on The Boldest, on Cloggy. However The Cad posed an interesting question. If a hard route could be well protected (e.g. a crack), then fair enough, failure might be contemplated. But what if it was as poorly protected as The Cad? Could you use bolts? In 1978 the prevailing view was that you couldn't.

A hugely important proponent of the ground-up approach

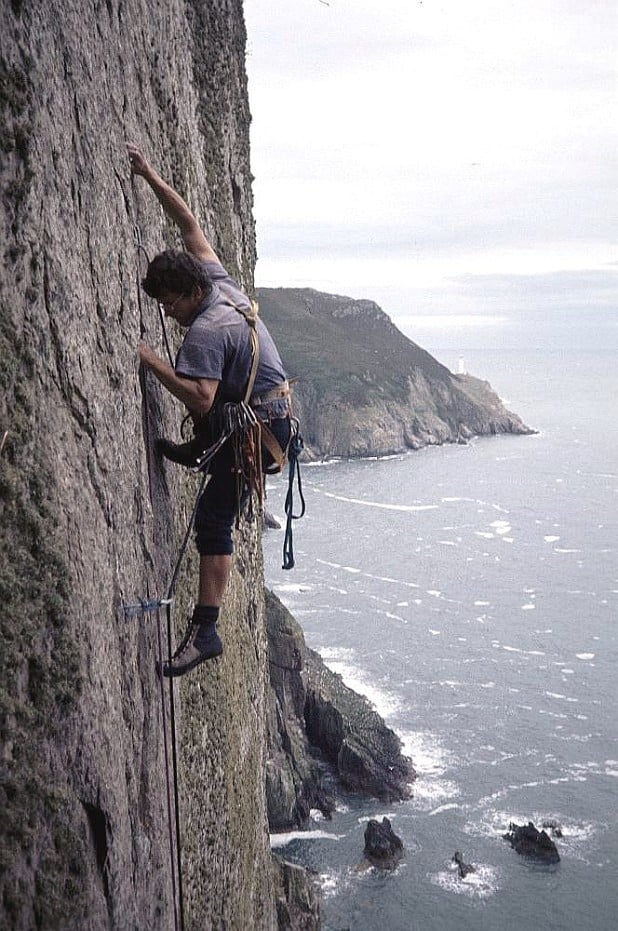

Climbing a new line ground-up as engagement with the experience versus operating top-down to produce a 'more professional' product... Increasingly the norm for cutting-edge routes was swinging towards the latter. However history is rarely simple. One hugely important proponent of the ground-up approach was Pat Littlejohn. Operating largely, though hardly exclusively on sea-cliffs, Littlejohn produced a plethora of undying classics. Eroica, Darkinbad, Il Duce... the list goes on, and on, (and on!) I hope we can all agree that abseiling into big, remote sea-cliffs and finding uncharted ways out massively adds to the adventure. A 6a move in such surroundings is often going to feel very different indeed from a 6a move on a Millstone crack with a wire comfortingly close to you. Originally operating with his close friend, Keith Derbyshire ('the boldest climber I've ever known' – gulp!) Littlejohn steadily increased his grade as the decade progressed. E3 became E4, then E5. By the early 1980s Littlejohn had amassed a probably unrivalled amount of ground-up experience. The result was seen in routes such as Alien (E6) at Gogarth, Above and Beyond (E6) at Fair Head and Guernica (E6) at Carn Gowla. As the 1980s progressed, he would climb still harder.

Looking back across more than 40 years, it seems to me that Littlejohn's importance was unfairly understated at the time. Yes, his routes appeared in the magazines but there was relatively little media coverage, e.g. no profiles or interviews. Littlejohn 'just got on with it' in much the same way as Pete Whillance and Dave Cuthbertson did. The Littlejohn approach of forging big lines on highly intimidating sea-cliffs can be seen in the later activities of such people as Martin Crocker, Mick Fowler and Dave Thomas. Dave's onsight FA of Terra Cotta (E6) at Berry Head and Fowler's remarkable Breakaway (where, it seems, the 'modern' XS grade is richly deserved!) at Henna will always stand as prime examples of adventure climbing. Still later, this approach can be seen in the North Wales exploration of the Lleyn (where Littlejohn again figured) and areas such as the back of Wen Zawn.

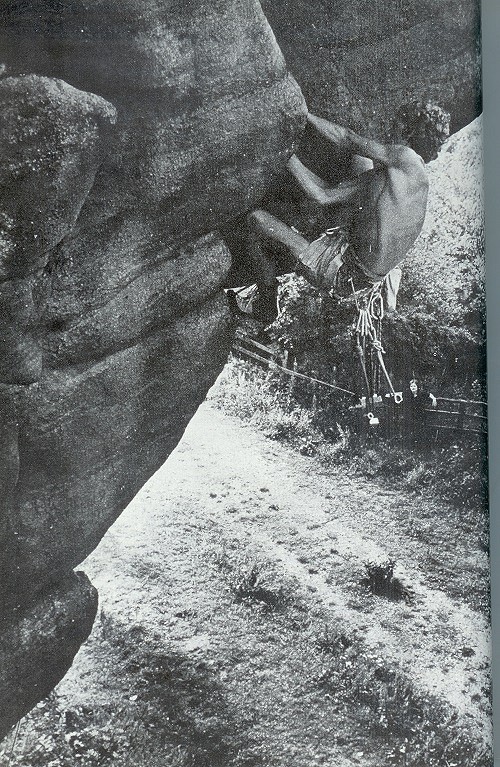

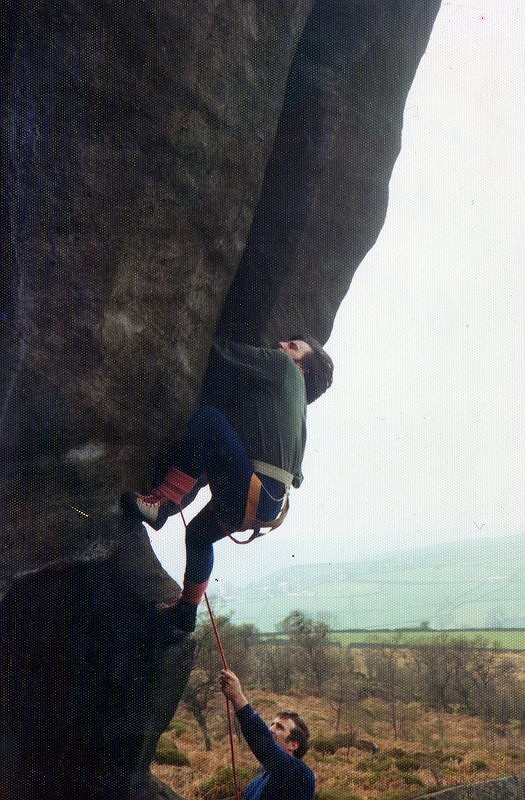

Jerry Peel heading into a world of overhanging offwidth horror, long before big cams existed. First ascent of Giggling Crack, Brimham, 1977

Three American routes which hinted at the future of climbing

Meanwhile, back in the 1970s, came three routes from America which hinted at the more conventional future of climbing. Ray Jardine climbed The Phoenix (5.13a, i.e. 7c+) with the help of his new invention, camming devices which he called Friends. Although Mark Hudon made the second ascent with hexes, as far as is known, he is the only person ever to climb The Phoenix without cams. Cams made it possible to place protection quickly in cracks. But Jardine hadn't just placed protection quickly. Shock horror – he'd also sat on the gear and worked moves. In fact he was well-known for doing so. To Americans, this was 'hang-dogging', most definitely a term of abuse. But it did mean you could climb harder.

The second route was Jim Collins' Genesis (5.12c/d, i.e. F7b+/c). Although this wasn't a crack, it was an old aid line, so there was gear to clip. But whereas The Phoenix was more like Livesey's London Wall type of hard climb, Genesis was more like a Profit of Doom or a Nectar – a very technical crux followed by still hard moves. Genesis was bouldering in the sky. As with other top US boulderers such as John Gill and Pat Ament, Collins was an ex-gymnast with an ex-gymnast's ability. It's rumoured that he took some 100 attempts at Genesis before success. Shock horror – might he have been hang-dogging too?

The third route was Tony Yaniro's Grand Illusion (5.13c, i.e. F8a+) Grand Illusion follows a wildly overhanging groove with a crack in the back of it, so it too could be protected (assuming you could hang around to place gear). Grand Illusion was the world's first 8a+ before 8a had been climbed. It took the methodology of The Phoenix and Genesis even further. Yaniro was rumoured to have spent two years working the route and built a replica of key sections to train for it. Sounds like yet more hang-dogging!

The Phoenix, Genesis and Grand Illusion showed that you could climb harder than ever before on relatively safe routes. They showed that you could climb harder if you could work the moves. And Grand Illusion showed that specific training could have an immense effect.

Two very different types of E7

The redoubtable Jim Moran on the first ascent of Barbarossa, Gogarth

Where did this leave British climbing? In 1980, John Redhead made the first ascent of The Bells, The Bells (E7) at Gogarth. In the same year, Ron Fawcett made the first ascent of Strawberries (E7) at Tremadog. The Bells, The Bells was Livesey's Linden-type route – a bigger, more demanding version of Linden on worryingly snappy rock. Strawberries was Livesey's London Wall type route – but significantly harder than London Wall. You could contemplate failure on Strawberries but failure on The Bells was almost unthinkable.

By 1980, with enormous respect to people such as Pat Littlejohn, the traditional British ground-up approach had reached somewhat of an impasse when it came to pushing climbing standards physically. No matter how bold you were, was it wise to attempt to onsight first ascents as hard and as dangerous as The Bells? You might - or might not - get away with a few inspired leads. But surely it was only a question of time before you incurred serious injury, if not death?

Strawberries posed the problem in a different way. Because Fawcett was held in such respect, the dread word 'hang-dogging' was never mentioned. On the successful ascent, pre-placed (and pre-clipped?) gear had been used. Clearly normal ethical standards had been breached. But, given such a sustained route, with so many hard moves, wasn't it naive to think that ethical standards wouldn't be breached?

Also of course Strawberries was a crackline which could be protected. But the UK doesn't have that many super-hard cracklines. What would happen with routes harder than Strawberries which didn't follow cracklines? How could they be protected?

The prime 1980s innovators – Livesey and Fawcett – had climbed widely both at home and abroad. The French had seen how climbing had moved on. Climbing standards in America had roughly paralleled those in the UK – until The Phoenix, Genesis and Grand Illusion.

The bitter lesson of the stone children

The lesson of The Phoenix, Genesis and Grand Illusion was that, to climb physically harder, you would have to accept failure. Indeed you would have to embrace failure, for eventual success. But how could you do that when a snapped foothold or a fumbled move might mean death?

British climbing has always lauded boldness. We revere Kirkus, Brown, Whillans because they were bold. In the 1980s, British climbing would achieve iconic boldness with Johnny Dawes' inspired Indian Face. But you can't climb routes such as Indian Face on a regular basis. You'd die.

For further progress, cutting-edge climbing needed to become safer. In the UK, in 1980, embracing failure for eventual success was a decidedly radical notion.

We've come a long way from 1960's Vector (E2) to 1980's Strawberries (E7) and The Bells, the Bells (E7). And the 1980s would see even greater advances. But these advances would only be achieved at the cost of a schism which risked tearing British climbing apart.

Tony Willmott was the original stone child. He personified the 1970s hard climber – ripped, long-haired, a wild gleam in his eyes. A generation emerged in his image. We naively imagined that if we were hard enough and climbed hard enough we could get up well-nigh anything. So many died: Don Barr, Roger Baxter-Jones, Sé Billane, Mick Burke, Pete Boardman, Keith Derbyshire, Nick Estcourt, Simon Horrox, Bob Hutchinson, Alex MacIntyre, Al Rouse, John Syrett, Joe Tasker, Gordon Tinnings, Rob Uttley and Tony Willmott himself. There is some truth in the claim that this generation - my generation - virtually climbed itself into extinction.

We were stone children. Even now, almost half a century later, many of the survivors remain stone children. Something still calls to us, far too powerful to be denied. Our first love may yet be our last. Who knows where our stories end? All we know is that we must go on, as best we can.

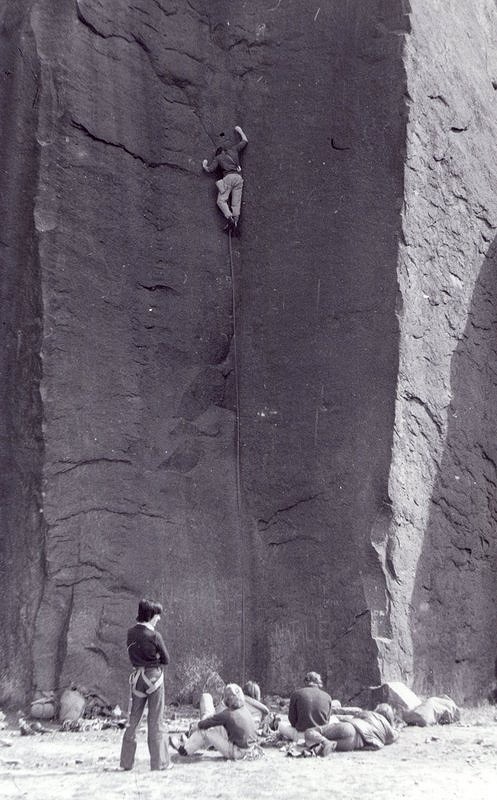

The fabled poster of Ron Fawcett on L'Horla, Curbar

With very many thanks indeed to Geoff Birtles, Loris Doyle, the late Al Evans, Jerry Peel and John Stainforth for help with photographs.

- IN FOCUS: Custodians of the Stone 5 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: Clean Climbing: The Strength to Dream 31 Oct, 2022

- ARTICLE: Thou Shalt Not Wreck the Place: Climbing, Ecology and Renewal 27 Sep, 2022

- ARTICLE: John Appleby - A Tribute 28 Mar, 2022

- ARTICLE: We Can't Leave Them - Climbing and Humanity 9 Feb, 2022

- ARTICLE: Staying Alive! Climbing and Risk 9 Jun, 2021

- ARTICLE: The Vector Generation 21 May, 2020

- OPINION: The Commoditisation of Climbing 2 Mar, 2020

- ARTICLE: 10 Things to Do at a Sport Crag 27 Aug, 2019

- ARTICLE: Ed Drummond (1945-2019) - A Retrospective 6 May, 2019

Comments

Eroica and Darkinbad were abseil inspected and had preplaced pegs on the first ascents.

Totally agree, Steve. But generally speaking, his approach was ground-up. Wasn't Alien onsighted? And I suspect you'd have a hard time toproping Above and Beyond.

Mick

Thanks Mick, a good read but you ignored Scotland almost completely (just an in passing mention of Cubby & a photo of Doug Scott aid climbing) so hardly "the key players in the climbing scene and major British ascents of the 1970s" .

Great article, but I'd have loved to hear more about the Lancashire heroes. Hank Pasquill's route Constables Overhang in Wilton 3 still gets E5 6b. First climbed in 1974 it must have been one of the hardest routes of the time, in fact it's still bloody hard today.

Andy F

I started climbing in 1983, and despite the advantages of better, gear, shoes and knowledge came no where near matching the acheivements of the generation that came before me.

Great article Mick.