Andy McVittie talks us through elbow tendinopathies and the follow-up steps in solving them after the initial steps of reducing pain and improving strength. For more information, visit Andy's website here.

My aim in this second article is to show you how to be successful in taking your tendinopathy from the standard rehab goal of getting pain free to beyond what caused it in the first place. This is the missing piece that ensures you can climb pain-free in the future.

Many climbers, with a short bout of tendinopathy, successfully return to climbing by following a protocol similar to the first article. But the injury often reoccurs when they start to try hard again.

Last year I saw a climber with a decade long history of golfer's elbows. Every time they tried to achieve their target grade it returned. Their partner continued improving and they got left behind. As demotivation set in, they sank to the depths of road cycling. Tragic! What was missing? A monitored increase in climbing levels and functional strength work. Both will be covered in this article. Adapting their post-rehab training to suit their loading profile (the characteristics of their climbing/training) and their goals was key. It only took one appointment to give them the knowledge to put into action. Simple sounding – but how do we do it?

To provide an example for the article we will analyse a sport climber with golfer's elbow.

Prior to progressing to this stage, you should be well on top of your pain and have built strength back up so that left matches right for your rehab exercises, like the examples from the previous article. This is a rough guide. There are more climbing specific, individualised, measures of when you are ready to progress to this stage, but we don't have space here.

So, your affected side now matches your unaffected side. Great! But your unaffected side is now weaker than it was pre-injury. How did that happen? It's probable you reduced, or stopped, climbing related activities at some point. If your elbows didn't have the capacity to deal with the challenge before, they're even less likely to now.

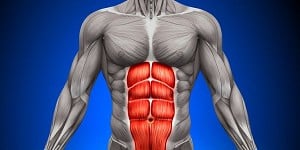

Elbows will be the most affected, but your entire body could be de-conditioned compared to pre-injury. How much depends on the effect the injury has had on your activity. With a comprehensive rehab program, all areas would be covered including trunk and lower limbs. This is not included here due to lack of space.

This article provides you with guidance to make a plan that should work for most people, most of the time. Individualisation plays a big role in deciding suitable exercises and protocols.

What to address in your plan will be discovered through a needs analysis.

There are 3 parts to the needs analysis. The same framework can be applied to any activity or tendinopathy. The table (below) shows the thought process used to analyse the climbing specific activities and choose an appropriate exercise and protocol. More detailed explanation is given below:

1) Loading profile of the affected muscle and tendon that require strengthening

Sounds good, but what does it mean? It's an assessment of the way the affected muscle and tendon will be used during climbing. For our example of a sport climber with golfer's elbow, this would be repeated, moderate to high intensity, isometric contractions of the wrist and finger flexors. Fingerboarding suits this well as a controlled, variable exercise.

Protocol choice depends on your goals and main climbing type. Bouldering, trad, multi-pitch, Winter, sport, indoors or outdoors? All require the affected tendon and muscle to work in a slightly different way.

2) Improving the load capacity of the kinetic chain

Single arm pull down – focus on the movement coming from the elbow, brush it past your side and keep pulling it back until your hand is on your ribs.

The kinetic chain is the series of joint relationships that make up a movement.

We don't climb with one isolated muscle group. But some are more important than others for performance and some are believed to be more important than others for injury prevention. The theory is that by strengthening the other muscles involved we can reduce the load on the affected muscle and tendon. It will, of course, also strengthen the affected muscle and tendon and due to this a tendon strengthening based protocol is recommended.

Using our example of our sport climber with golfer's elbow, strengthening of the shoulder girdle and shoulder blade could reduce the load of the elbow.

I recommend a heavy slow loading (HSL) protocol to strengthen tendons.

Eccentrics are very popular for tendinopathies, but I would not recommend these in this instance for the following reasons:

1) Tested eccentric protocols require around 180 reps a day, over two sessions, every day. This can take hours and lead to stress if people miss sessions.

2) HSL is performed 3 x a week. It's much easier to fit into your life.

3) Most of the studies supporting eccentric use were in lower limb tendons. The Achilles in running does a very different job than the wrist flexor in climbing.

4) There is a need to address the concentric aspect of the rehab also in climbing and HSL addresses this.

This should be thoroughly thought out. Where is the weakest link? Is it a strength or endurance-based capacity issue? Is it actually a skill/movement deficiency? (see section 3 below).

In some cases (often combined with movement dysfunction/awareness issues) the kinetic chain may be addressed through unweighted tasks or light theraband work.

3) Addressing movement dysfunction

Movement dysfunction can add to injury risk or occur due to an injury as you change your movement to accommodate it. It's often a chicken or egg scenario.

This is a complex area in an open skill-based sport like climbing. Climbers must be able to move in a variety of ways and adapt rapidly to changing situations, but still produce accurate and effective movements by controlling the forces acting on them.

I may be accused of bias but as a coach, I believe improving technique is vital for reducing the risk of injury. Climbing routes indoors over winter 3 times a week can mean hundreds of moves per week. It is this repetition that can gradually overwhelm a joint if technique is not at a suitable level to reduce peak force loads.

There are some great online resources around technique. If you don't know what you're looking for the technique and skill articles on UKC are a good place to start your road to constant improvement.

|

Variables to consider – what happens during climbing? |

Examples |

Exercise examples |

Protocol | |

| 1) Loading profile for muscle and tendon |

Dominant muscle action: Repeated isometric contraction of finger and wrist muscles |

Crimping a hold - Pinches |

Fingerboarding - Pinch block deadlifts |

Density hangs prior to progression through strength endurance to pure strength protocol (max hangs) and power work. . Low (2 out of 10) or no pain sessions with load reduced as required to achieve this. Elbow/wrist angle and grip positions can be adjusted to target specific tissues. |

|

2) Improve load capacity of entire kinetic chain |

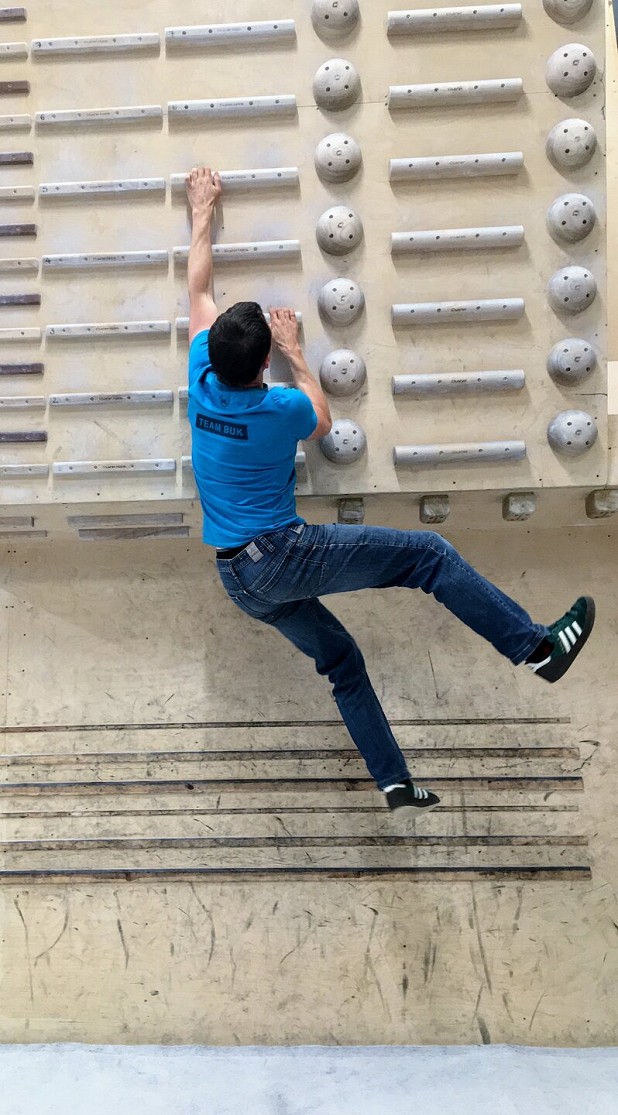

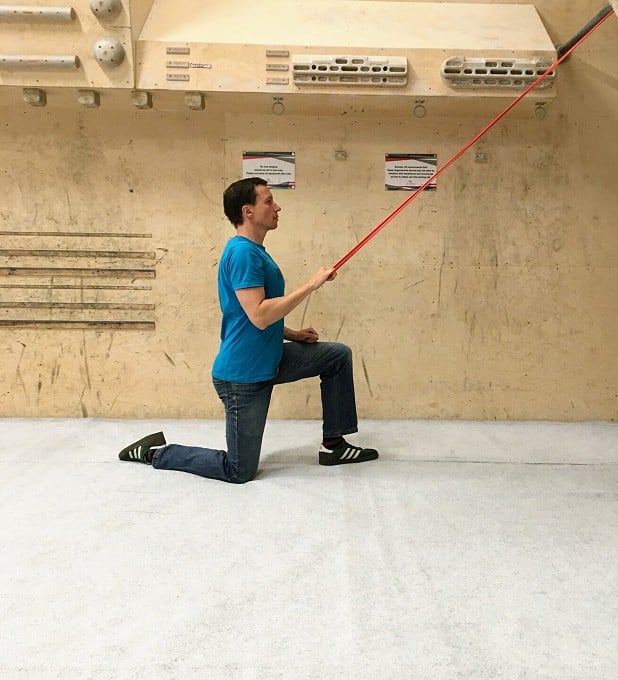

Dominant muscle action: Bending of elbow from extended overhead and bringing the upper arm into the body. |

Maintaining contact with a hold whilst making upward progress or ability to maintain a static position |

Single arm kneeling cable/theraband pull down - Supine rows on rings |

Build strength in muscles that may help reduce load on the affected tendon during function. Strength building of affected muscle and tendon, but less provocative for elbow than a finger based grip: Heavy slow load protocol as described in stage 1 of previous article. You may include static holds at certain elbow angles. 8/10 effort or feel like you could just squeeze one more rep out. Only work in low/no pain free range. This range will increase as strength increases. Position of hands adjusted to stimulate symptoms. Progress angle/load as ability increases leading to more familiar strength building protocols and work at a higher rate of force production. |

| 3) Identify movement Dysfunction linked to increased tendon load | Changes in joint range or movement control that can increase muscle/tendon load |

Changed climbing style to accommodate pain experienced through tendinopathy. Previous climbing style that excessively loaded the elbow tendons through static and non-fluid climbing – including climbing on arms that are too flexed and not deadpointing holds. |

Technique drills focussed on fluidity of movement |

From the example in the table, you can see we use this approach to break the big picture into manageable and distinct chunks. The muscle(s) and tendon affected (the finger and wrist flexors) have had their 'job' identified. Their 'job' in sport climbing is generally to perform repeated, medium to high load, isometric contractions.

From there we have identified the kinetic chain they are involved in for climbing – from the wrist to the elbow, to the shoulder, and into the trunk - and given example exercises and protocols to follow.

A final word regarding the protocols. Exercises chosen depend on the functions of the muscle – a hamstring tendinopathy would look at the function of the hamstring as a knee flexor, hip extensor and as an eccentric stabiliser in running/walking. A brachioradialis injury would look at elbow flexion, pronation and supination. There are not many muscles that perform only one function. All areas of their 'job' need addressing through strengthening.

In the previous article there were 3 further rehab phases:

4. Increase power - Tendons can be quite speed sensitive in relation to pain as the rate of force production is increased.

5. Develop the stretch shortening cycle

6. Sport specific training

Again, the specifics of the phases require individualisation. Rate of force production and the stretch shortening cycle are much more important for a boulderer than a trad climber, who requires the ability to hold static positions for periods, fiddling gear in, as they shuffle from ledge to ledge.

We are also fortunate as climbers that we can practice a diverse range of moves, in a diverse range of situations as we gradually return to previous levels. Have a focus in your climbing sessions on gradually doing more powerful moves, or holding static positions.

Increasing our rehab and climbing related activity levels through these phases requires monitoring to reduce injury risk. Tendons can take 24 hours to react (become painful) and up to 48 hours to positively adapt following stimulation (they need adequate recovery time).

I recommend using a structured monitoring system that covers both objective and subjective measures. Fortunately, I have one here that can be used to help you assess when something is no longer a niggle and is an injury, whether you're pushing your rehab/training a bit too hard and how to progress safely.

As a climber, climbing coach and physiotherapist (who has also done a fair bit of running and cycling), Andy is ideally placed to provide clarity and direction to your return to climbing and outdoor sports.

A life long climber, who started coaching 13 years ago, he has coached on Spanish performance improvement holidays, sport climbing, competition climbing and helped people achieve everything from ascents of El Cap to their first V11. More recently he founded a youth competition climbing squad https://processcoaching.me/ with his business partner Ellie.

Whilst his focus in coaching is technique based, his passion in physiotherapy is education, strengthening and a detailed, fully supported, return to sport. This background enables a unique, blended, treatment approach, with an in-depth knowledge of all aspects of how climbing impacts the body.

2020 was going to mark his proper return to sport climbing with an aim of 7c onsight. Fingers crossed it may still happen…..

- GEAR NEWS: The Self Rehabbed Climber, by Andrew McVittie 5 Dec, 2022

- SKILLS: Core Training for Climbing 15 Feb, 2022

- SKILLS: Improving Heel Hook Ability and Reducing Injury Risk 22 Apr, 2021

- SKILLS: Treating Elbow Tendinopathies whilst in Lockdown 6 Apr, 2020

Comments