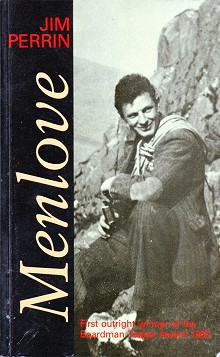

My cousin spent the last six months of his life sorting out his climbing library to pass on to the Alpine Club. All except one book, the anthology 'Mirrors in the Cliffs'. It's an excellent anthology – but compiled by that scurrilous and unacceptable fellow, Jim Perrin. Perrin's offence: exposing the great climber John Menlove Edwards as gay.

'Menlove', the book that caused such offence to the Alpine Club member – and this was less than 20 years ago – was also one of the first winners of the Boardman-Tasker Award for Mountain Literature.

Perrin is a fine writer, in the 'Marxist literary critic' tendency. And Menlove Edwards was an interesting man – and in particular, an interesting climber. But what makes this one classic are the extended extracts from Menlove's own writing. Basically, everything Menlove wrote that's any good (even including the better bits from the climbing guidebooks) is in here.

Before World War Two Menlove Edwards was climbing in Wales harder routes than anybody else, and more of them. Many of the current classics at V Diff to VS are his. But it wasn't just his climbs that were extreme. What makes this book, and Menlove's own writings, so intriguing is Menlove himself. Loose, slippery, unreliable, vegetative and difficult is the description applied to his signature climbs on the Devil's Kitchen, and Menlove himself was much the same. Apart from not having the Snowdon lily growing out of him.

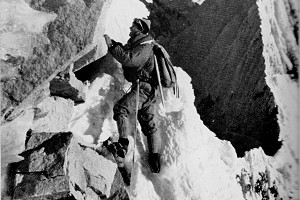

Sometimes new standards in climbing come from new and better, meaning safer, kit. Menlove climbed old-style, in nailed boots, rubber-soled tennis shoes, or occasionally in his socks. Sometimes more difficult routes are down to some climber's unusual talent or rigorous training. Menlove was talented, yes, and he pushed his body hard. But Menlove's specialty was simpler. When it came to taking risks, Menlove Edwards took them.

It's not always easy to tell from the account of a climb just how difficult or dangerous it was. Fortunately there's an easier way to assess that aspect of JME than re-enacting his on-sight climbs while using 1930s kit. Because he was also, and like the poet Shelley, a person who did dangerous stuff in small boats. Very small boats. Like a canoe, solo, from the Isle of Man to Cumbria. A collapsible canoe. In winter.

He also swam down the Linn of Dee, in spate conditions. But he did abandon the attempt to sail across the North Sea in a leaky dinghy he didn't actually know how to sail.

If Menlove Edwards lived his life in the style of the damp, slippery, unstable, unreliable black basalt of the Devil's Kitchen, his writing style is much the same

When faced with an extraordinary bit of climbing or mountaineering, sensible people find themselves asking: was she or he mad? Were they trying to kill themselves? And if sensible people who happen to also be climbers don't ask ourselves those questions – reading this book will ask them for us. Mad? Suicidal? Menlove was, or became for the last six years of his life, a paranoid schizophrenic – hospitalised and subjected to insulin coma and ECT 'therapy'. And in 1958 he did indeed kill himself, using an especially dreadful method, Prussic acid.

Plus, of course, Menlove was gay, at a time when this was hugely discriminated against and also against the law. Thus, a half-century on, causing 'Mirrors in the Cliffs' to be added into my own library rather than the Alpine Club's one. It's an excellent anthology, taking its title from one of Menlove's essays and including another of them in the book. (Can an anthology be added to the list of Mountain Literature Classics? That's a question for another column, another month.)

Biography relies on the illusion that we can empathise with and understand another human being. Of course, all human life depends on that illusion. Biography breaks down when the biographee gets diagnosed with mental illness. Menlove was paranoid. But then again, they really were out to get him. Homosexuality was a crime, the disgrace and death of Oscar Wilde was still fresh in memory. And then the Germans came over in aeroplanes and started dropping bombs on him.

Alex Honnold has spoken of the bottomless pit of self-loathing that motivates some free solo climbing. Applied to Menlove, this would be very harsh. But too harsh?

If Menlove Edwards lived his life in the style of the damp, slippery, unstable, unreliable black basalt of the Devil's Kitchen, his writing style runs with the theme. 'End of a Climb' and 'A Great Effort': these may be Menlove's most celebrated bits of climbing writing. The style is taut, vigorous, and self-analytical, to match his climbing. But each of them is actually a self parody. 'End of a Climb' is set at the top of a gripped-up V Diff. 'Great Effort' applies his taut etc analytic style to the self-justifications of a failed climb. It's a funny piece, too: though the laughter is harsh. Read it on Footless Crow.

In 1937 Menlove came back from Norway with a copy of the banned Ulysses by James Joyce hidden in his rucksack. But should the style of a rock climbing guide really be modelled on that tremendous literary classic?

Well, Menlove's literary style does exactly match his style of climbing. Of The Runnel (S), on the East Buttress of Lliwedd: "It is worth while on even the best of cliffs to have a large supply of routes and on some of them to have the whole type of interest more varied and general… Thus, where the others try to avoid such a thing, this climb clings to grass, heather and the wider interest of a friable type of rock…. Standard: Difficult or Very Difficult. (Today's grade: Severe – or, slightly less infrequently, Winter II. Menlove undergraded most of his routes.)

'Up Against it', the piece about his month (August 1938) working on the Lliwedd Guide, is even more Joycean.

It's no good telling chaps like you trash about all we did. You wouldn't be interested. It's new stuff you want, we weren't really on for that, we had work to do. We had meant to do some, but once we started ... you can't give up climbing, go soft, without an insidious weakening coming on, and so it was with us, we found. We had to do the ordinary climbs first.

Menlove's harsh, ironic style gives nothing away: he actually put up 12 new routes in the 'indolent' month's work. Up Against It's a surprising piece for a climbing magazine, containing as it does zero in actual climbing. Maybe the editor included it, as with 'The Runnel' on Lliwedd, as a bit of variety among all the boring normal stuff (read it here).

So turn instead to 'Little Fishes', his early boat trip across to Skye, as published in the Wayfarers' Club Journal.

In the Wayfarers' Club everybody is fashioned by both nature and training to be almost imperishably tough and durable. It is said that a member can be left out for 48 hours in a thunderstorm without commencing to look sodden…

The boat was lazy in the little harbour waves: too old it seemed, and sodden, to rise to them... There were also three oars and all had bent in their time and bent widely, beneath the stress of circumstances. If they bent any more they would certainly break across.

The seats were thin and hard. Then the wind took us and we got among waves. John Sheridan was in the stern and spread his ample oilskins to keep out the white horses. They came and climbed up his shoulder, then with a gurgle of displeasure slid along the length of the boat, spilling a little over the edge. We baled them out again…

The sky was a dirty, dull colour, and even the bubbles of the white horses took on the grey. The only relief was the dead white line of spray breaking on the Skye coast.

This is the very opposite of the soft snow avalanche of feeling in some contemporary hillwriting. This is the hard rock poking through. Deeply internal, but cold and ruthless like a surgical knife. How does he feel as the rowing boat is blown towards the line of surf breaking on the schist rocks of Sleat? He leaves that to our imagination – we're human beings, we can imagine things. But what is he doing in the boat anyway, what brought him there, what makes him do this thing? As well as becoming clinically insane, by the definition of the day, Menlove was to become a psychiatric doctor. One who described certain climbs as "not a sport, so much as the brief symptoms of some psycho-neurotic tendency".

For me, Perrin's book has rather too much Perrin in it. But it also has about as much Menlove as can, reasonably, be communicated in words and writing.

But to experience Menlove in a more meaningful way – just hit Shadow Wall (VS 4c), or Flying Buttress (VD) or Crackstone Rib (S 4a).

Or the one the waitresses took Eric Newby up on his way to Afghanistan. The one Menlove wanted to name as Sodom. For an authentic Menlove moment, make your way to Dinas Cromlech in the Llanberis Pass, and climb the climb called Spiral Stairs (VD).

- Mountain Literature Classics: The Wildest Dream by Peter and Leni Gillman 14 Aug

- Mountain Literature Classics: Harry Griffin, the alternative Wainwright 12 Jun

- Mountain Literature Classics: WH Auden's In Praise of Limestone 2 Dec, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog 15 Feb, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: South Col by Wilfrid Noyce 9 Jan, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: Free Solo with Alex Honnold 29 Nov, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: That Untravelled World by Eric Shipton 3 Aug, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight 4 May, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North 12 Jan, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Conquistadors of the Useless by Lionel Terray 17 Nov, 2022

Comments