Following a spate of avalanche-related deaths and injuries in the Scottish mountains recently, we are re-sharing this 2-part series on avalanche awareness and safety skills by Mark Reeves, first posted in 2012.

From the still-evolving science behind them to tips on how best to avoid getting caught out, avalanches are a huge and complex subject. But even a little knowledge could be a life saver, whether you're a winter novice starting from scratch or a seasoned old hand just wanting a quick refresher. In this two-part article Mountaineering Instructor Mark Reeves explores the basics. Part 1 covers the mechanics of avalanches, and part 2 gives some advice on staying safe.

This article is derived from Mark's new e-book A Mountaineer's Guide to Avalanches, now available on Kindle, and for ipad.

Whether you like it or not, if you choose to head out into the hills of the UK in winter then avalanches are a real threat to your survival. Wherever snow lies there is a potential for an avalanche to occur. For many assessing the danger seems like a dark art only mastered by experts. It should be the responsibility of everyone who takes to the hills in winter to have a basic understanding of avalanches.

'It is the responsibility of everyone who takes to the hills in winter to have a basic understanding of avalanches'

This article should open the door to greater understanding and knowledge. However it is up to you to explore further as you develop as a winter hillwalker and mountaineer. All we can do in this article is put you in the starting blocks and help start your journey in the right direction. Here I cover the anatomy of an avalanche, and in the next part I'll look at some practical ways to stay out of trouble.

In the UK most avalanches are described as slab avalanches, in that one of more layers of snow slide down on either lower layer(s) or the ground. As yet we have found no truly foolproof way to predict when these will occur, but through the study of snow and avalanches we can at least estimate the odds. In essence we make an educated gamble.

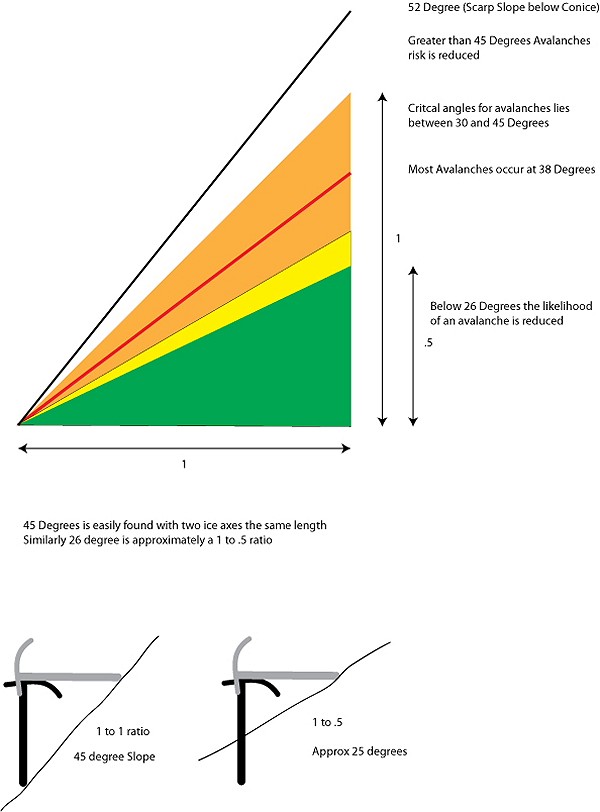

We know for instance that avalanches are most likely to occur either when its snowing or within 24 hours of snowfall. Avalanches are most likely to occur on slopes between 28 degrees and 45 degrees, although they can happen on slopes outside these limits, just more infrequently.

'Avalanches are most likely to occur on slopes between 28 and 45 degrees - though they can happen on slopes outside these limits too'

Tension and resistance

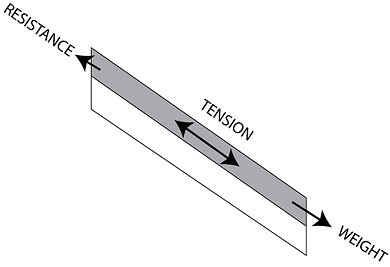

In order to understand why and how a slab avalanche formed it is good to first examine why for much of the time the snow doesn't slide at all, but stays where it is. A slab of snow can stay in place because its weight and the downward force of gravity are not enough to counteract forces that are holding it in-situ. These forces are the resistance the layer(s) of snow have against the each other, and the amount of tension that the layer can hold before it fails.

The resistance can be illustrated by placing a block of wood on a plank, and tilting the plank up until the block starts to slide. Obviously in an avalanche the slope doesn't increase in angle; it is the weight of snow or the friction between layers that can change.

An increase in weight with the falling of rain, snow or people standing on the slope can help overcome this friction; similarly a change of temperature in the snowpack can decrease the resistance between layers, reducing the friction. All increase the likelihood of an avalanche.

The tension is best described as how well bonded the snow is, as the bonds between individual grains are what helps keep the snowpack together. Each of these tiny links in the snowpack make the snow stick together and as the weight starts to stretch the snow it is counteracted by the tension of millions of tiny links. Just as a carabiner can hold a massive amount of tension and then suddenly snap, the same catastrophic failure is evident in avalanches.

The tension in the snowpack can be affected by three factors: the increase or decrease of the bonds within the snow, localised weaknesses in the snow and the weight.

Key Points:

- Avalanches are most likely to occur within 24 hours of fresh snow

- Avalanches are most likely to occur on slopes angled between 30 and 45 degrees

- More snow, rain or the extra weight of a mountaineer will increase weight and the chance the slope will avalanche

- Rising and falling temperatures will affect the stability of the snow

- Aspect and Altitude of the slope affect snow stability

- Avoid Cornices and scarp slopes where possible

Bonds

A decrease in the tension the snow can support before failure is one of the reasons that avalanches are more likely to happen within 24 hours of new snowfall. If the snow falls as stellar crystals, the interlocking arms of these millions of snowflakes make a well-bonded snowpack. However as the crystal metamorphoses and rounds these arms start to retract, and the bonds between crystals may weaken enough to increase the likelihood of a slope avalanching.

After that initial weakening of the bonds, the snowpack can gradually strengthen again. As the crystals start to neck together and sinter, more and more tiny links between them are made. As those bonds between crystals start to grow, so does the strength of the snow, making it less likely to fail under the tension. Given enough time to make bonds the snowpack can become very stable.

But as well as becoming more stable snow can also lose cohesion over time, with a rise in temperature in a well-bonded snowpack. This reduces the strength on the bonds between each crystal, as each frozen link can potentially start to melt.

Human triggers

There are also unnatural ways to affect the 'breaking strain' of the snow by creating a stress point. A skier's tracks or the footsteps of a mountaineer for instance can potentially break key bonds, just like adding perforations or folds to a piece of paper make it easier to tear.

Terrain

The other potential problem with the tension in the snowpack is from key natural stress point like convex slopes where at the apex the snow will be under more tension than in other areas. This is why convex slopes are best avoided.

Similarly a wide open and expansive slope that extends a long way down a flat hillside will be under far more tension than a short slope broken up by protruding boulders or vegetation, where the irregularities in effect help anchor the snow to the ground.

A further factor in avalanches is the aspect or direction the slope faces. The risk of avalanches changes greatly over even a single mountain in the UK, often due to these two factors.

Altitude

Another factor in avalanche hazard is altitude. Simply put, a greater volume of snow falls higher up. There is also the temperature to consider, as at lower altitudes we get higher temperatures so the snow will sinter and round together quicker, either stabilising the snowpack or melting it entirely. Higher up the temperature may remain below freezing for an extending period, and as a result the snow will take longer stabilise.

Wind and windslab

Due to our weather being generally brought in with frontal systems the snow when it falls rarely stays in the same place; it will be blown from windward slopes onto lee slopes. Here's where windslab is found, often creating localised accumulations on high summit ridges and in sheltered gullies. Windslab is formed by new or recently fallen snow being broken up into smaller crystals and transported by the wind. These smaller crystals pack together closely and build into large slabs of snow. These well-cohered layers do not bound well to underlying layers, making them prone to avalanche. Windslab is brilliant chalky white snow which doesn't glisten and has the squeaky feeling of a knife being pushed into polystyrene; watch out for these warning signs.

Due to prevailing winds slopes that face in one direction can be totally different from those facing in the opposite direction. This is why avalanche forecasts use a wheel, so they can highlight the aspects most affected by avalanche hazard.

As well as accumulations in leeward slopes, we can also get accumulations in cross-wind slopes, where slight dips and ridges provide leeward shelter for snow to accumulate. This is often referred to in avalanche reports as 'cross loading'.

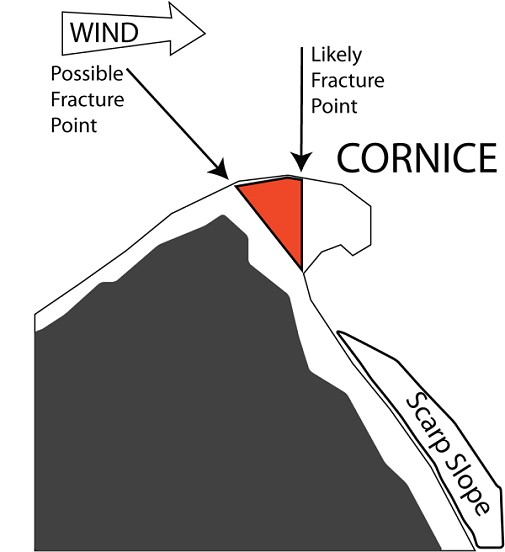

Cornices

A further effect of the wind is to produce cornices, overhanging edges of snow along ridges and cliff tops. These often form when the snow is brought in on a wind of 10 to 50 mph. On the lee side of the ridge snow accumulates creating an overhanging 'crest of a wave' type feature. These often collapse, either in thawing conditions or simply under the weight of new buildup, or the addition of a person on top of them. Anyone caught beneath a collapsing cornice can be bombarded by tons of snow.

Cornices also have what is called a scarp slope directly below them. A scarp slope is essentially a very steep accumulation of windslab, that is usually around 50 degrees in angle - an angle often far beyond one that snow will normally settle at. In short, for either walkers above or climbers coming up from below, cornices can provide a very real danger, a hazard to be given a wide berth if possible.

A key to avoiding cornice hazards is to understand what areas they are likely to have formed and be cautious if you HAVE to venture close to them. Wherever possible make navigational decisions to avoid them, especially in Scotland where cornices can build up rapidly near the summit and can be totally hidden in the whiteout conditions for which the Great British winter is known.

Plan ahead, and ask yourself if it's sensible to be climbing below known cornices if the temperature is set to rise. Winter climbing areas like Aonach Mor and Creag Meagaidh are notorious for collapsing cornices in the thaws that sweep through off the Atlantic.

The Scottish Avalanche Information Service (SAIS) gives the following factors as the top reasons for avalanches:

- Visible avalanche activity. If you see avalanche activity on a slope where you intend to go, go somewhere else

- New snow build-up. More than 2cm/hr may produce unstable conditions. More than 30cm continuous build-up is regarded as very hazardous. 90% OF ALL AVALANCHES OCCUR DURING SNOWSTORMS

- Slab [Windslab] lying on ice or neve, with or without aggravating factors such as thaw

- Discontinuity between layers, usually caused by loose graupel (icy pellets) or airspace

- Sudden temperature rise. The nearer this brings the snow temperature to 0 degrees C, the higher the hazard, even if thaw does not occur

- Feels unsafe. The "seat of the pants" feeling of the experienced observer deserves respect

- 90% of avalanches involving human subjects are trigger by their victims

This article is based on A Mountaineer's Guide to Avalanches by Mark Reeves, available as a ebook in two formats: for iPad at £4.99 and for Kindle or ePub readers via Amazon at £5.14.

Mark Reeves is a Mountaineering Instructor and Winter Mountain Leader who runs coaching and skills courses through his own business Snowdonia Mountain Guides. During the winter months he spends a fair bit of time in Spain nowadays hot rock climbing and coaching through Sunnier Climbs. As well as this Mark now spends around half of his time writing guidebooks for Rockfax and a Coaching Column for Climber Magazine. He has authored North Wales Climbs and North Wales Slate for Rockfax. His current projects include a guidebook to the Mountains of Snowdonia and another to North East Spain. He has several iBooks out soon too, A Mountaineer's Guide to Avalanches, Hanging By A Thread: The History, Science, Technology and Culture of Rock Climbing and Mountaineering and Effective Coaching: A Rock Climbing Instructors guide to the Coaching Process.

Check out his blog to see what else he is up to.

- PRESS RELEASE: 30-Week Instructor Training 2020/21 19 Jun, 2020

- Sunnier Climbs - Hot Rock holidays 25 Jun, 2019

- ARTICLE: Avalanche Basics Part 2: Staying Safe 20 Mar, 2019

- ARTICLE: Sea Cliff Climbing Safety 10 May, 2017

- New North Wales Rock Climbing iPhone Guide 30 Nov, 2011

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Llanberis Slate - The Full Tour 30 May, 2011

- Llanberis Mountain Film Festival 22 Mar, 2011

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Tremadog - North Wales 26 Oct, 2010

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Llanberis Pass 4 Mar, 2010

- Bardsey Ripple Sundae 7 Dec, 2009

Comments