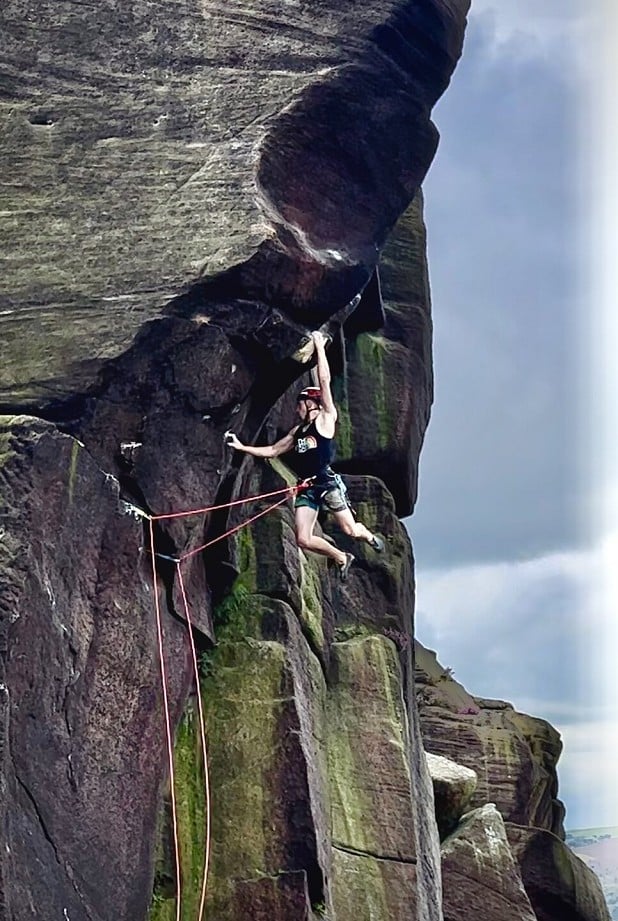

James Pearson has made the fifth ascent of the 'post-break' Parthian Shot (E10 6c), at Burbage South Edge in the Peak District.

The ascent comes just two weeks after he made the third ascent of Prisoners of the Sun (E10 7a) at Painted Wall, Rhoscolyn.

Whilst James' ascent is the fifth since the flake broke, and the second this summer, it is believed to be the first post-break ascent where the climber hasn't placed a side runner in the nearby Brooks' Crack (HVS 5a), whilst also placing all of the gear in (what remains of) the flake on lead.

We spoke to James earlier today, and he sent us over some thoughts about his ascent, as well as some musings on the history of the route and how it has developed over time.

Parthian shot is a route that has lived several different incarnations, both in the minds of aspiring climbers, and through the loss of crucial holds and protection.

First climbed in 1989 by a very on form John Dunne, Parthian was said to be certain death should the climber run out of steam high up on the wall. That myth was broken in 1997 by Seb Grieve when he fell whilst attempting to make the second ascent, and in the years that followed after multiple climbers had taken the same ride, the route became known as one of the safer hard routes on grit.

The quest for the first ground up ascent came and went, claimed by the visiting American Kevin Jorgeson in 2008, who like many other climbers chose to lead the route with pre-placed (and pre-clipped) protection.

Then one day in 2011, the flake broke!

In one fall Parthian went from being a sport route in disguise, back to a potential killer (Will Stanhope was lucky to only end up in hospital), and to make matters worse, the best hold (also the best gear placement) had completely broken off the wall. Was it even climbable? For years nobody even tried, until Ben Bransby took up the challenge in 2013 And made the first re-ascent. To compensate for the decreased protection quality, Ben opted to place a high side runner in the crack on the right (Parthian Shot begins in this crack) to reduce the load on the fragile flake and offer a fail safe backup should it break again.

Improving yet again on Ben's ascent, Neil Mawson climbed the route in 2014, placing all the protection on lead, as John had first done back in 1989, though still with the high side runner. A further break to a second part of the flake in 2023 changed the route again, and whilst this time the protection was unaltered, the climbing to gain the flake became significantly harder, and placing the gear even more exhausting. The visiting Italian Jacopo Larcher was the first person to lead the route in this state in July 2023, making a very impressive quick ascent, using the high side runner but placing all the protection on lead.

The obvious challenge however still remained…

Parthian might be my longest running Gritstone project, at least for routes I've actively been trying. I first looked at it back in 2004, when it still had all of its holds, and remember being blown away by how steep and pumpy it was!

As a younger climber there was just no way I could have done something like this, and even once I had developed the fitness, I always found the top boulder desperate enough to put me off ever wanting to try it above the terrible looking protection.

When the flake broke and the high side runner became standard practice, it almost became an easier objective in my mind. Yes, the gear in the flake was even worse than before, but with the extra protection on the right you basically had a 'baby bouncer' (two ropes running through two pieces of protection, separated horizontally by a few meters, but placed at the same height), and from looking at video of the fall of Ben, it seemed a nicer fall than before.

My approach to trad is fairly simplistic, and I try to play by a basic set of rules. Firstly, always try to match or improve on what has been ethically done before. Then, start on the ground, climb the route, placing gear wherever you climb, and hopefully get to the top. Obviously things are never black or white, (let's avoid talking about headpoint vs flash vs onsight for now), but side runners and pre-placed gear are two things I really try to avoid. I decided that if I wanted to one day lead Parthian Shot, I'd do it like John. Gear in the flake alone, placed on lead, knowing I shouldn't fall.

Parthian Shot has always been climbed starting in Brooks' crack, and after a no hands rest in the corner, it traverses for two moves leftwards onto two crimps, and the first big move up into the base of the famous flake. Instead of this traditional start, I chose to start down and left, climbing the same initial arete as the route Dynamics of Change (E9 7a), but on its right hand side, before swinging right onto good holds in the face, placing a couple of friends, and doing the first hard move to join the aforementioned Parthian crimps.

Whilst this start is slightly harder than the original, it doesn't really affect the difficulty of the overall route. I climbed it like this simply to avoid the possibility of placing the side runner in Brooks' crack, and to create an logical and authentic way to find yourself on the head wall with only the poor wires in the flake, without having to follow ambiguous rules

It's worth mentioning that there has been another alternate start to Parthian Shot climbed in the past, which, in theory climbs directly up the slab to join where I placed my first protection. I say in theory, because I've never seen any video or photos of people actually climbing this, only some very vague descriptions. and after checking out the slab on a couple of occasions, I still really don't understand what you are meant to do.

Whilst it is possible to climb only using holds in the slab, the holds constantly lead you towards the left arête, and it feels very 'forced' not to use it. The line up the slab alone would definitely be harder than what I climbed, but it seems a bit daft to me to force a harder, more dangerous route by eliminating obvious holds.

The day of the lead went well. I climbed the route on my first try of the day, the protection went in quickly and efficiently, and I had plenty to spare on the crux and the upper slab, which really allowed me to enjoy the whole process. These days, when I climb a potentially dangerous route, I need to be fairly certain I won't fall, or I just won't set off in the first place.

Regarding the danger of Parthian Shot, it's actually a really hard one to judge. The wires themselves are not too bad, and a couple of them are quite deep, but the flake is undeniably hollow, and since the wires are all pretty small it's hard to say exactly what will happen when you take a big fall and it expands.

When I asses gear placements on trad routes I try to give each piece a mark out of 10. 1 is total rubbish that can barely take the weight of the protection itself, and 10 would be a number two friend in a deep, solid granite crack. The four pieces I placed in Parthian are individually between 4 and 6 out of 10, assuming they are placed perfectly, nothing bombproof by any means, but they all happily take bodyweight, and some of them would probably hold a small fall.

As is common with small wires and sliders, the placements are very sensitive to climber error, and if placed even slightly out of the optimal position they can go from being OK to useless. For example, the best of the two sliders works well because of a small crystal blocking the sliding ball. Misplace the ball and the slider won't stick, and the same would obviously be true if the crystal were to crumble… sadly, the rock on that face is not the most solid of gritstone after all.

However, I clipped the four pieces in two separate pairs, roughly equalised with different length quickdraws, on separate (very thin and stretchy) ropes, and I have a feeling like that the cluster has a good chance of holding a fall from the rock-over on to the slab.

Don't get me wrong, I had no desire to test my theory and wouldn't suggest anyone go for it balls to the wind, but I wasn't climbing as if I was soloing. We'll only really know if it will hold or not when someone takes the lob, and if it does turn out to be ok, what really scares me is that eventually, given enough abuse it will one day fail again. How many falls this might take is anyone's guess. All I can hope is that people take a little more care with themselves and the route than they did in the early 2000's. Perhaps at the end of the day the side runner is actually a good idea?

Finally, on to the difficulty… The most recent hold breakage (2023) has done quite a lot to change the difficulty of the route. Instead of making a static move up to a decent undercut, you now have to dyno from the two crimps just to get into the base of the flake.

The previous good hold at the base of the flake is now a one handed (still fairly good) sloper, so it's hard to swap hands and a lot more pumpy to place the first few pieces. I actually placed the majority of the gear from the upper part of the flake, which - whilst far from a restful position - allows you to better see where you are placing your gear.

For me it was essential to place each piece perfectly to stay calm for the climbing yet to come, and this takes more time than just stuffing them in. I've never climbed the route with the high side runner so this is pure speculation, but I assume I'd be a little less stressed knowing I had a backup to catch me should the gear in the flake fail. All this means that when you set up for the big slap from the flake to the slopers above (now a very hard move since the breakage in 2011), you are already pretty tired. Success in the route came down to relaxing and recovering enough on these slopers to have enough juice for the crux, and obviously not panicking on the rock-over and final slab.

Comments

Great write up and description of the process by James Pearson.

Just shows how cold it’s been in August. Unreal.

Not sure what he's on 😁 - that bottom wall doesn't look like a slab to me.

But really interesting to see his views about the protection and his ethics in trying to always do in the best style so far or even "better".

That top slab rockover move still looks f***ing scary though.

Isn't that more a yo-yo than ground up?

Love the retro Hard Grit music on the video, takes you right back to the late 90s!