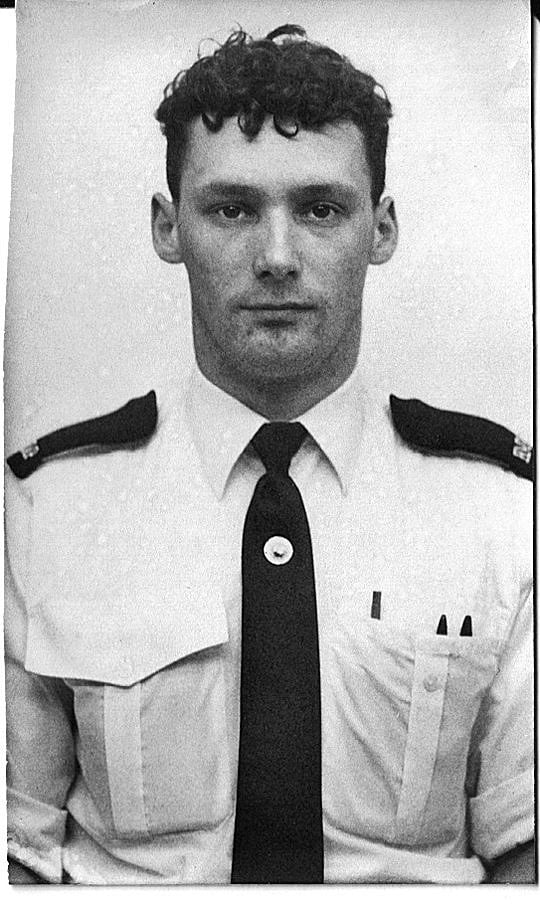

It's a strange world we live in now, as social media warps our perceptions of what people are like in real life. I fall victim to this as an endless stream of photos and videos from top climbers flicker before my eyes. All-round mountaineer and author Nick Bullock, 53, has now been a full-time climber for longer than any other job he had previously. This chosen path has taken him all over the world living, by his own admission, 'a selfish existence'; fuelled in the earlier days by arrogance, determination and a desire to push on regardless.

I wanted to find out for myself: Who is Nick Bullock? What has his chosen path given him, taught him and taken away from him? One thing Nick did seem to understand early on was that the act of choosing to leave something behind is not necessarily a sacrifice and that comfort is not a substitute for peace of mind. Sitting with Nick in his house just outside Llanberis one afternoon, I was privy to the complex thoughts and feelings of a man whom I had once assumed to be dogmatic.

The truth, as I discovered, could not have been further away from my own preconceived notions. Nick is a sincere, caring and affectionate human being who is able to articulate his feelings well and provide comfort to those around him. He's environmentally aware, socially conscious and, at times, subject to his own demons.

Here's what he had to say about his story so far.

You've written extensively about what mountaineering and alpinism have given you. Great adventures, new friends and a freedom that you never had prior to quitting your job as a PE Officer in HM Prison Service. On the flip side, what has the choice to climb taken away from you?

Mountaineering and alpinism has not given me freedom; the decision to leave full time employment gave me freedom. The question you're asking is, what opportunities have I lost in life by giving up working in the Prison Service, or to use your words, what has been taken away? In some way, the question I suppose should be, what are the disadvantages of the life you now lead in comparison to your old life? In reality, nothing was taken away, I chose to leave certain things behind.

Several weeks ago, in China, there came a point when I had been living the life of a full-time climber and writer, longer than the time I had worked in the Prison Service, (the time I spent in the Prison Service was fifteen years) so that was quite a moment! In a way, your question can only be answered retrospectively, because climbing and writing is my life now, and with every day, it becomes the longest single thing I have pursued that could be called a job. I would have answered the decision to leave full time employment took away security in the form of money being paid at the end of each month. A pension. The same place to go home to, with the same things around me and personal space. That's it really, because anything else is speculation, and even then, the correct way to describe it would be, these are the things that I chose to live without, or do without for an unspecified period of time.

I would like to say the satisfaction of working in the Prison Service was taken away, but that would not be correct. At times, the work did give satisfaction, but not very often, and it was getting less satisfying because of government cutbacks that affected the quality of service, and the opportunity for rehabilitation. Cutbacks also affected the safety for both incarcerated people and the people working inside the prison, this is something we can see the results of today, with the difficulties frequently being reported in the media .

A thing I didn't value as much as I should have perhaps was the relationships with friends who also worked in the Prison Service, and the relationships with some of the people who were incarcerated. I would like to think that in some small way I made a difference to their lives, but in the end, I walked away for my life. It could be deemed a selfish act?

The thought of people in the world who live on a daily basis with terror, war, without food, poverty and without a home is beginning to affect me. If I had continued to work in the Prison Service, I would have had more money than I needed for myself, and with that extra finance, I could have donated more to food banks and charities etc., but it's all guesswork, maybe I would not have thought this way if I had continued to work in a prison, maybe it's by living the life I now live that makes me more aware of other people's struggle?

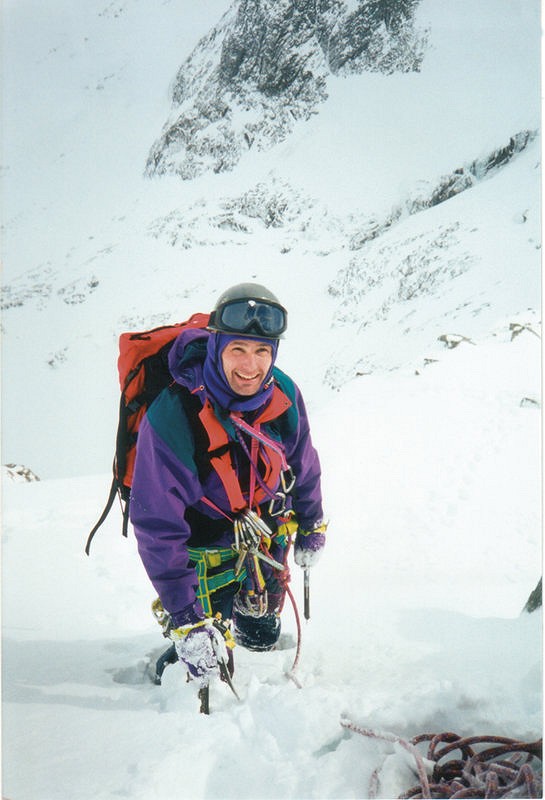

You wrote on your blog about a recent trip to Minya Konka in the Sichuan Province and mentioned Paul Nunn's accidental death and how he was the same age as you are now when he died. Has the thought of "your time to come" weighed on your mind the more expeditions you have under your belt? And if so, why do you think this is?

I don't really understand statistics, but the more you put yourself in a place of danger, the more you have a chance of being hurt or killed. Minya Konka was my 24th expedition to the Greater Ranges, which means that over the years, I have placed myself in a position of danger frequently, so, in my mind, the chances of something happening to me is high. There is also the fact that over the years, I have had several close friends, and people whom I knew well, killed in the mountains. It was on my mind quite a lot in China, especially given the isolated nature of the mountain, the fact that Paul and I chose to climb by ourselves, the dangerous approach to the South Face and the difficulty of the climb.

You once described how the word comfortable meant the death of uncertainty. In fact, it was this notion that contributed to you finding the courage to quit your job full time. Does comfort still mean the same thing to you now as it did 25 years ago, are you still fearful of it?

The thought of being 'comfortable' was not the only reason I chose to leave a full-time job, in fact, it was not a reason at all! The main reason I wanted to leave my work was to climb, and then write about my experiences. It would be easy for me to go through life being comfortable, and why not, comfortable is a pleasant place to be, but once you get settled, it can be difficult to get moving again. Being stationary means you don't leave the ground - not a good option for a climber.

There is definitely something inside me that is haunted by the thought of being stationary, but as I grow old, being relaxed is possibly not a bad place to be, but there is also a part of me that finds relaxed difficult, which is possibly good, because at times the thought of where I will be in ten years is a scary one. All said and done, it's pretty easy for me as a climber living in the UK to say how overrated it is being comfortable, and how comfort is the death of uncertainty, because it's an attitude of privilege. How many people in the world would love the comfort of clean water, a guaranteed meal, a bed, a home, good health, no bombs, no war. No, comfort does not mean the same to me now as it did back then.

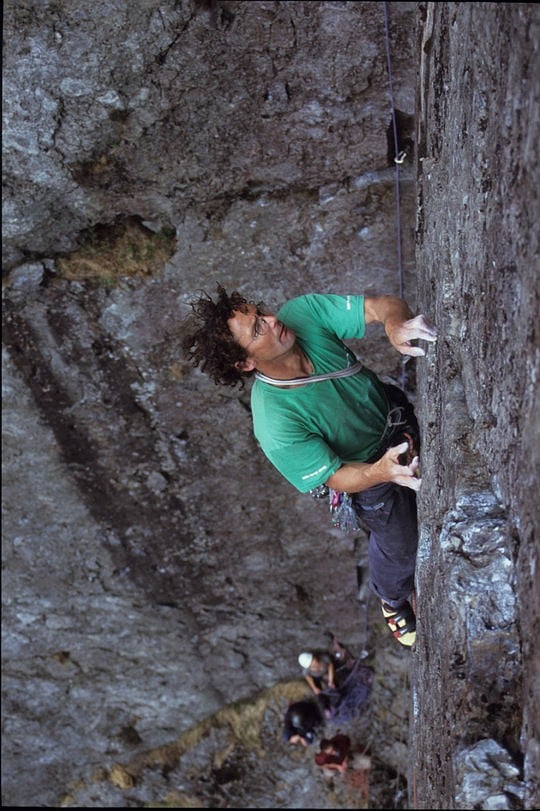

The face of climbing has changed significantly during your 25 years of participation; big brands entering the game, overwhelming numbers of people being attracted to the outdoors and climbing is now a recognised event in the Olympics. What impact do you think this surge in popularity has had on the activity?

When I began to climb, the activity gave me a feeling of finding my own way, exploring, taking risks, breaking free of the 'normal', of course I could never truly break free from the normal, but this is the feeling I had when I started to climb. Climbing felt different from sport that has referees and rules and regulations; climbing gave me, and many others, a chance to explore, not only the hills and crags but also ourselves, we could make choices without too much outside influence and without too much backlash. Without doubt, climbing has changed, and its rise in popularity is one of the biggest changes. Change can be good; the benefits for improved physical and mental health for a large number of people. The involvement of young people, especially with the competition and indoor aspect. The increase in job opportunities. The large number of modern climbing facilities. The increase in popularity of films, podcasts and climbing culture, and with the rise in numbers, there comes a voice, and with this voice, comes influence, support and access.

Sport climbing, especially abroad, is massive now, and it's great; I love travelling around Europe in my van, climbing and clipping bolts, what a fantastic and privileged existence. Time moves forward, this we cannot stop, and with it, change is inevitable. I understand and accept this completely, but the involvement of big business is, for me, one of the real downsides to popularity. Climbing is now influenced by big business, and these businesses have no concern or attachment to climbing, apart from making a profit. Big business uses advertising, and through this advertising, at times obvious, sometimes subtle, we become conditioned to think along similar lines, want the same things, want things we cannot afford, or experiences we cannot have, and with this, climbing is losing uniqueness and independence and the individual loses control and perspective.

With the involvement of big business comes the ability to make big money, which also does not sit with the climbing I became involved with. Not wanting to get too political, but there appears to be something of a neoliberalist attitude taking over aspects of climbing. We are led to believe that any climber can become rich from their activity, which is OK I suppose if that's what you want, but I feel this attitude brings about a loss of the grassroots, and with money, comes selfishness, hubris, greed, a lack of integrity, dishonesty. I see young climbers who are brilliant and very excited by the prospect of the Olympics, who can fault this, not me, but I also see kids crying with frustration and pushy parents. I see consumerism and advertising hitting children's events and offering false hopes, I see role models who purposely, or maybe ignorantly, push big business philosophy.

I wonder if, in part, this Olympic element is brought about by the rise in a marketable aspect of climbing and the ability to make money from it? There is definitely a gulf between the traditional aspect of climbing with its values, and the competition element, and the gap is growing to a point where climbing on rock and competition climbing have become entirely different, but to what end I'm not sure.

There is also another aspect of the rise in popularity of climbing that concerns me, and that is the pressure on the climbing areas, on the flora and fauna, the crags and the rock. There are now areas, summer and winter, swarming with climbers. If we want to continue to use these areas, we have to respect and look after them. We also have to respect the other people using these areas, because you will not be on your own; far from it, the days of solitude have long gone.

Another massive change from 25 years ago is the reporting of climbing. At one time, news was only reported once a month in a magazine, now it's everywhere. Again, it's just time and advances, but I'm not sure this immediate, unedited, unconfirmed reporting, Instagramming, Facebooking, tweeting etc. is an advance. And with this 'advancement' in reporting and technology, like webcams and temperature reports of the turf, people appear less willing to walk-in and try a climb, or make a decision on its condition, without an up-to-date report from someone else. In my opinion this is a big loss. The excitement of not knowing what you may find is almost a thing of the past, and this was a big part of Scottish winter climbing and Alpine climbing for me; taking a punt and it coming off gave almost as much joy as the act of climbing.

Finally, the click bate reports and false or at least incorrect reporting from many websites, almost makes a mockery of our activity, it dumbs down, misinforms and annoys. I really don't think climbing needs 'the five best this', 'the ten best that'; climbing is, or at least was, better than this, in my mind. Climbing reporting at many levels has now become about money and profit and numbers of visits. We have to have clicks and visits to be viable, it's a bit of a sorry state.

With 24 expeditions under your belt to the greater ranges of the Himalayas, what moment stands out above the rest and affirms that your decision 15 years ago, was the correct one?

It's a good question because it makes me think about the routes and experiences I wouldn't have had if I was still working in the Prison Service, and there are many. The one, stand-out route, would be The Slovak Direct on the South Face of Denali, which I climbed with Andy Houseman in 2012. I would select the Slovak, because later in the year, I was going to Nepal with Andy to attempt a new route, and because this climb was in Nepal, and a new route, it would have taken precedence over an established climb in Alaska - even one like the Slovak. Also, because I enjoy all forms of climbing, I wanted to stay in North Wales for the summer to rock climb, but Andy convinced me to join him on Denali for nearly 2 months. Yes, my rock climbing suffered, especially because seven weeks later, Andy and I went to Nepal, but living the life I now live meant that after returning from Nepal I could go to Spain and clip bolts, although I think I went to Canada to climb ice!

How did your journey into writing begin? Did you have any instigators or mentors along the way?

The main instigator and mentor was, and still is, a poet from Leicestershire called Mark Goodwin. Mark worked at the Tower Climbing Wall and we became friends. On my return from trips; the Alps, the Greater Ranges, Wales, Scotland, wherever, I would tell Mark about my experience, and he would beg me to write about it, but I never did. Then one evening, in 2000, my friend Jon Read picked me up outside HMP Welford Road, the prison that looks like a castle in the centre of Leicester, and we joined the Tuesday Night Crew at High Tor. A member of the crew was Ken Wilson. Ken found out where I had climbed, and some of the climbs I had attempted, and he told me I should write about them; in fact he was insistent, but he also said he would help.

Soon after meeting Ken, I travelled to the Alps with Paul Schweizer, where on the second go we climbed the Dru Couloir, on the Northwest Face of the Petit Dru, after bailing from the first attempt in a storm. I decided to write about it in the campsite. I had no writing paper, but I had driven in my van, so I salvaged big brown envelopes to write on. On my return from France, I sat with Mark in the climbing wall, where we wrote a piece about the experience. Ever since then I have written. In the early years, I sent my writing to Mark, and after Mark and I edited it, to Ken. Ken saved all of my writing, because he intended to publish my first book, but he became ill before this happened and died in 2016, which was a great loss to climbing.

Where do you see the next 25 years of climbing taking you? More trips to the greater ranges perhaps or more writing?

Not wanting to get too morbid, but in 22 years' time, I will be 75, the same age as my Mum was when she died. It's quite sobering, because 22 years is not that far away! It hit me hard when Mum died, because my own mortality somehow became more apparent, and it has affected a part of the way I act and think. Greater Ranges trips are exceptionally rewarding, especially when you reach a summit. It's a cliché, but there is nothing to match the intensity of emotion when coming down and reaching safety after climbing a new route on a big hill. Unfortunately, big trips take a massive amount of time, energy and money.

They also affect the time before, and the time after the trip. The last thing I want to do is get injured falling from a rock climb, and this really plays on my mind; it affects the climbing I choose on the run-up to going away. I also have to train for most of the summer before an expedition to make sure I'm at my best aerobically; running, cycling, circuit training, and this also eats into a large proportion of my time, time I would prefer to be rock climbing. Since I'm older, expeditions are a big commitment and the pressure of making my remaining time count grows. That said, never say never, although I have said never again a few times now, but the right line on a 6500m mountain with the right partner would still tempt me, and I'm still very keen to climb a few more big Canadian alpine routes, or climb in Patagonia, or attempt some big single push semi-alpine climbs, which, all said and done, is more climbing than is usually achieved on a climb in the Greater Ranges.

Writing is an important thing for me, I have enjoyed writing from day one, and yes, I do want to continue. Maybe it will take over from climbing as my body grows even older. I have two ideas for new books that I'll start to work on soon.

Did you ever envisage this level of success in your climbing and writing career after you completed your PE Officer training and ultimately discovering climbing for the first time? What were your expectations back then?

It's a difficult question to answer, but to clear up a couple of things, I don't really look upon my climbing as a career; climbing always has been something I do because it gives me satisfaction, not remuneration. I'm not saying other people don't get joy from their chosen career paths but climbing for me was something different to a career. Similarly, for my writing, although less so, because I do write for payment, and at times it does feel like work. I didn't write when I trained to be a PE Instructor, or at least, I didn't write in the way you mean, so it's impossible to answer what my expectations were, but to take the question in a general sense - no, I never expected to reach the level of climbing or writing that I have, although I'm still not sure what level this is, but it was not what I set out to do. I don't think anyone set out to make a career from climbing in 1992, because the opportunity to do it wasn't there, or at least, not for someone like me, a pretty average climber.

In 1992, all I wanted was to go climbing and experience the places and the people and live through similar experiences to some of the people I read about at the time, Chris Bonington, Joe Brown, Hamish MacInnes, Al Rouse, Alex MacIntyre, Joe Tasker, Pete Boardman, Paul Pritchard, Adam Wainwright, Johnny Dawes, Andy Parkin, Nick Dixon.

You say, "Did you ever envisage this level of success?" It's an odd one that because what is success? I have climbed routes I never imagined capable, on both rock and in the mountains. I suppose this is success, and it gives me great satisfaction, but I've also lost friends and lost touch with friends and lived selfishly. I would not deem this successful. On the writing front, I think I always wanted to have at least one book published, but I think this is a thing many people dream of, but having a second book published is a success, at least a second book that is better than the first, which I think I achieved with Tides.

What does comfort mean to you now?

Comfort could be getting through the day without upsetting anyone, or without feeling guilty or by helping someone in some way. Comfort may also mean attempting to live a better life by reducing my impact on the planet by being more responsible by the choices I make in the food I buy and who I buy from in general. I would also like to say comfort is living a life where travel is less important, but I'm still guilty of travelling lots and playing my part in damaging the environment, so in the future, I need to address the balance.

- INTERVIEW: James McHaffie - The Cumbrian 28 Sep, 2020

- INTERVIEW: Mina Leslie-Wujastyk - The Journey so Far 3 Oct, 2018

Comments

Good interview but I suspect Nick would be the first person to cringe at the praise in the third paragraph of the intro ;-)

Enjoyed reading this! Thanks

Thanks Nick, and Mark for allowing a little insight.

We all need to keep following our desired path and on the way try a little harder to help others while being free to chose life and respect all.

Keep em coming Nick.

PS great opening image of Nick, Mark well captured.

Keith s

Hey Keith. Thanks very much. I am glad you enjoyed this piece. I completely agree with your sentiment.

Haven't had the pleasure of meeting Nick but am an admirer of his writing and climbing achievements. This article reinforces my opinion.

AP.