Mick Ward reflects on the rich and varied life of climber and writer Ed Drummond, who passed away last week after a long illness.

Ed Drummond was probably the most visionary figure in British climbing history. He left a legacy of stunning routes and superb writing. And he had a reputation for having the most complicated, mercurial character imaginable.

Where does it begin – for you, for me, for any of us? Show me a hardcore climber of a certain age and, so very often, there's a troubled childhood. All those scary moves, all that striving for success. What's it really all about – a desperate craving for the approval - the love - of (often long-dead) fathers?

***

Drummond, like Icarus, fell. A classic act of hubris – trying to impress a girl, I believe. The year was 1964. The place was Pontesbury Rocks, in Shropshire. The route was The Superdirect. Today it's graded E1 5a. Drummond was 18, a beginner at climbing. In the 1960s, VS was the pinnacle of most climbers' careers. Hardly anybody climbed XS. Beginners certainly didn't. Drummond tried to solo it. He almost succeeded. And then there was a nasty landing.

***

In retrospect, The Superdirect was little more than a false start. A couple of years later, Drummond was studying Philosophy at Bristol university, living at 'Clifton in the rain', as Al Stewart memorably described it. Below him was the Avon Gorge. From 1966 onwards, he criss-crossed its seeming blankness with a network of routes which were often harder and scarier than any which had gone before. The Blik ('A stern test of both mind and strength, on one of Avon's most impressive walls.') Last Slip. ('A superb, bold and memorable climb.') Krapp's Last Tape ('An Avon rite of passage.') The Preter ('An airy voyage, taking in some of the Main Wall's best positions.') Ffoeg's Folly. Hell Gates (with logbook in the little cave). Limbo. The Earl of Perth. The Equator – a monster girdle of the Main Wall, with his chief partner in crime, the redoubtable Oliver Hill.

His guidebook, the aptly named 'Extremely Severe in the Avon Gorge', introduced the climbing world not only to the routes but to a grading system based on factor analysis. Drummond deconstructed routes in terms of factors, such as technical difficulty and protection (or lack of it), gave them weighings and thus ended up with final grades. Back then, there were no E grades. Extremely Severe (XS) covered a multitude of sins! Technical grades weren't widely used. Undoubtedly Drummond was on the right track. Unfortunately however, his system was too cumbersome to be accepted. One thing was clear though: the climbing world was being introduced to a person who wouldn't shy away from self-promotion or controversy. And, amid this grand intellectual enterprise, lurked the most wonderful howler. 'Stand on the peg without using it for aid.'

***

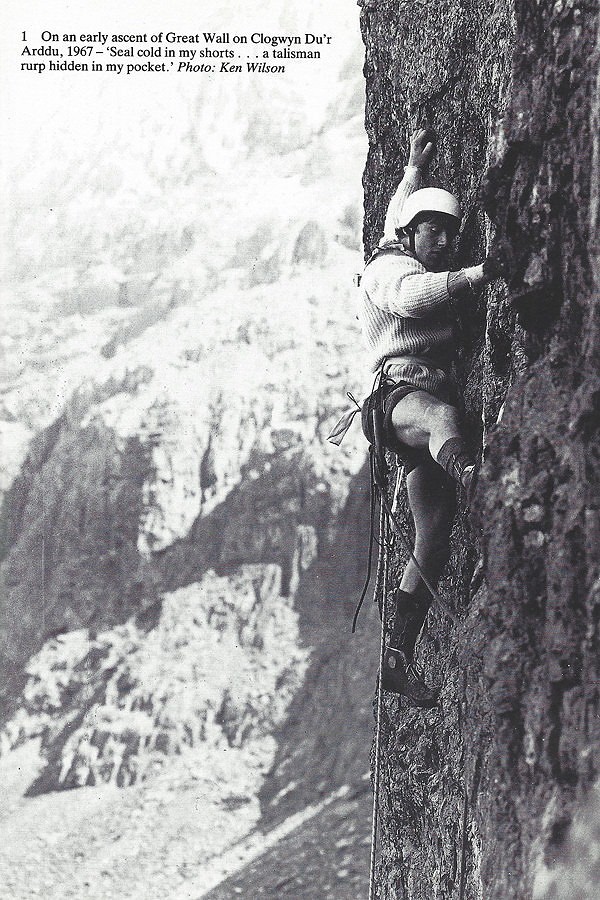

1967. If you wanted to test yourself against the best, there was really only one place – North Wales and one crag – Cloggy. Back then, you climbed hard, you drank hard and you partied hard. That was the deal. You didn't try to promote yourself in print. (You let your mates do that for you.)

Drummond was already married, with a young son. Understandably he wasn't much interested in drinking or partying. So he wasn't one of the lads. He hadn't got mates to do his promotion for him, so he did it himself – an unforgivable sin, in the eyes of the cognoscenti. 1960s bacchanalia versus nut crunching and date nibbling… A posh accent and a name like Edwin Ward-Drummond – well, you couldn't really make it up.

But how did he perform on the rock? A second ascent of The Boldest, the most feared route in Wales, was made in trademark style – slowly. In all, it took him three days. What on earth did he lower off – Crew's bolt, placed in extremis? The thought of lowering from shit 1960s gear makes me feel sick. And going back up again! Unperturbed, Drummond advertised in a climbing magazine, offering to take punters up The Boldest for £6 a pop. Brown's caustic riposte was priceless. "£6 – not bad for three days' climbing!"

Drummond might have done The Boldest slowly – but he still did it. The fifth ascent of Great Wall, made under the scathing gazes of Crew and Boysen, took him hours. A lesser man would have succumbed to the pressure; Drummond didn't. He was too naïve to realise that the entourage had come up to Cloggy for the sole purpose of watching him fail. But he didn't fail. And he wrote arguably the most iconic climbing essay ever, immortalised in 'Hard Rock' almost a decade later. The ending is famously poignant, timelessly elegiac. 'Five years ago. He was still in love with that wall. Lovely boy, Crew, arrow climber. Wall without end.'

***

Having done the two hardest routes on Cloggy, Drummond headed for the other premier venue, Gogarth. Although Crew burned him off on the first ascent of Mammoth, it was just another false start. His first ascent of The Strand was a tour de force. He graded it XS, 6b (the first attempted use of this grade in Wales?) and confidently stated that it wouldn't see a repeat for 20 years. The fabulously talented but wayward party animal, Al Harris, did the second ascent a few weeks later, while out instructing (hope he charged £6!) Once again Drummond's blatant self-promotion had proved his undoing. It was conveniently easy for his critics to ignore the superb quality of the route.

A year later, with Dave Pearce, Drummond climbed the undying classic of all classics, the route for which he is best remembered, A Dream of White Horses. For once, he didn't need to do any promotion. Leo Dickinson's stunning photograph, with the waves breaking an outrageous way up the crag, said everything. VS climbing in an XS situation guaranteed instant classic status. Interestingly this was a rare example of a Drummond route being upgraded. His original HVS went up to XS, for a time – to keep inexperienced people off the route. Don't forget, back then, there was rubbish protection gear (no wires or cams) and there would have been loose rock. In addition, virtually no climbers carried prusik loops. Nowadays, cleaned up by the passage of innumerable feet, with prusik loops and immeasurably better gear, A Dream of White Horses can be enjoyed as a relatively easy but thrilling world classic.

Drummond continued to produce the goods on Gogarth. At the time, routes such as T Rex and Afreet Street looked ridiculous – but he still did them, albeit with some aid. In those days, routes weren't generally cleaned from abseil and the perils of loose rock often forced first ascentionists into using aid which they otherwise wouldn't have needed. The Moon was described by Drummond as 'strictly space walking!' and appeared in Mountain magazine as, 'another crumbling horror… like an unrelenting, giant-sized Vector'.

***

Back on the social scene, success continued to elude Drummond. Risking the rigours of the Padarn on a Saturday night, he asked Leo Dickinson to introduce him to fabled Scouse hard man, Pete Minks. Fellow hard man Scousers Al Rouse and Brian Molyneux struggled to keep straight faces. "Pete, this is Ed Ward-Drummond." "Hello, Peter, I don't believe I've had the pleasure…" "And I don't believe you're going to get it," came the crushing reply.

If you're going to be damned anyway, well why not just go for it? Some of Drummond's routes in Wales, such as the outrageous Great Arête on Llech Ddu, were done in impressive style (and a little aid). Conversely his first ascent of A Midsummer Night's Dream on Cloggy was thus reported in Mountain:

'There has been an attempt to put up a new route on Great Wall… Four pitons and a bolt were placed and the line was top-roped first. This event has triggered widespread disgust in climbing circles.'

***

Having moved from Bangor to Sheffield, Drummond announced his presence in the Peak by abseiling into the stance of High Tor's Delicatessen to join Street and Birtles for the first ascent. Unwelcome or what? "I very much had the feeling of being watched and evaluated. But I'm born naïve, so I keep getting into these situations where I'm not quite sure what the code is and really not very interested in it." Drummond's contention that Birtles fell off was flatly contradicted by both Birtles and Street. The latter subsequently commented, "Drummond fell off… after he'd fallen, he said to me, 'Actually I didn't fall then, I slipped off!'" He'd taken about a 15-foot swing and gone crash, bang, wallop into the corner – arms and legs everywhere!"

Yet another false start… Unperturbed, Drummond beavered away at High Tor, substantially reducing the aid on Flaky Wall and Darius, renaming them Bulldog Wall and The Burning Icicle respectively. (When they were eventually completely freed, the original names were retained.) At Dovedale's Ilam Rock, he renamed The White Edge Easter Island, after a free ascent (very) loosely based on it. Ironically Rocksport, the leading magazine for UK climbing, argued in favour of the aid route! It seems that Drummond just couldn't win. In retrospect, it's clear that attacking such blatant challenges - which most people could never imagine being free climbed - was a bold, brave move in the right direction.

***

In the late 1960s, British climbers were slowly becoming aware of the big wall climbs which were being done in Yosemite. Was there a future for big wall climbing in Europe? Doug Scott and friends made an inspired ascent of The Scoop of Sron Ulladale, one of Britain's most impressive crags. In 1970, with his old Bristol friend, Oliver Hill, Drummond made the first ascent of the Long Hope route on Hoy. At the time, this was pretty much disregarded. Since then, it has justly achieved legendary status. For Drummond to embark upon such a big, serious route, leading up to E5, onsight, through tottering rubble, with shit protection was… something else entirely. Terror raised to the level of an art form.

It seems a little odd now but, back then, Norway's Troll Wall was viewed as the best contender for big wall climbing in Europe, our version of El Cap. Well it was certainly big enough - but size doesn't guarantee quality. Drummond's first attempt in 1969 ended when his companion, Dave Pearce, was hit by stonefall not far from the top. Their second attempt, the following year, was again defeated, this time by snowfall. Drummond's eventual 21 day ascent of the Arch Wall, with Hugh Drummond (no relation), in 1972, raised suffering to the level of an art form. His essay about their experience, 'Mirror, Mirror' is the finest example of obsession that I've ever read. Die for the route? Die for the fame? Die for the glory? Yeah… why not?

***

From the very big to the very small… In the first half of the 1970s, Drummond tackled some of the last great problems on grit: Flute of Hope on Higgar Tor, Guillotine, Archangel, Wuthering, Chameleon and Asp on Stanage and Linden on Curbar. Controversy continued to dog him. Archangel was top-roped first – a sensible measure, I'm sure most of us would agree. Flute of Hope had a resting sling (as did the nearby Rasp on its first ascent, by Brown). More troubling was aid on Guillotine. And, worst of all in the eyes of many, were two chipped 'dots' for skyhooks on Linden. In a famous letter to Mountain, Keith Myhill castigated Drummond: 'This event must surely mark the lowest point in gritstone climbing for a very long time.' Drummond's riposte in a later issue of 'Molehill' was delicious:

'…Rome wasn't built in a day, nor Cenotaph ascended by Saint Joseph without a pin here and a pin there. And Quietus top-roped first. I'm still learning how to learn. Silly Myhill. It isn't your hill. The route is there for you too. Go on – open your legs – let's see what you can do. Balancing on those two impeccable skyhooks should keep you quiet. You might even learn to pray; and not prey.'

Ironically Myhill had used nuts for aid on two of his own first ascents on grit. Nevertheless his argument is still valid. By the early 1970s, aid on gritstone was becoming distinctly passé. And chipping is obviously wrong (although Drummond was neither the first nor the last to resort to it). As Peak Rock rightly points out, 'In its free state, Linden is now graded E6 6b; that standard of climb simply did not exist anywhere in Britain in 1973.' In the early 1970s standards were soaring; a few years later, Mick Fowler signalled his emergence with the first free ascent. Shortly afterwards, the supremely gifted Phil Davidson made an astonishing onsight solo – thus proving what we all know. After Pex, everywhere else (yes, even Curbar!) is a piece of piss. To me, the thought of standing in slings on wobbly skyhooks seems far worse than free climbing and, aid or not, fluffing the top wall might well have meant a crater in the ground. Drummond may have been controversial - but he was undeniably bold. And, to his credit, he repented, in an interview a decade later.

'I erred and was willing to err. If you are creating something, to a degree you have a right to define the way in which to create and I was willing to chip holds… I was different, in that I was wilful and was prepared to change the rock to suit me because I was at the cutting edge and had a right to blunt it a little. I was wrong.'

***

Then, like some meteor streaking across the firmament, suddenly he was gone. Emigrated to San Francisco. From 1966 to 1975 he'd blazed a trail across British climbing, left a legacy of brilliant routes, albeit ones sometimes mired in controversy. To my generation, coming of age in the 1970s, he was a mythical figure. A few of us had met him; most hadn't. I hadn't. I'd always been fascinated by him, wondered what he was like.

In the summer of 1982, dropping into a Sheffield pub after an evening's cragging on grit, Ian Jones and I bumped into Simon Horrocks. When Simon casually mentioned that Drummond was back, on a fleeting visit from San Francisco and they were going out on Stanage the next day, I was enthralled. Wouldn't it be brilliant to do an interview with him? Accordingly Ian and I turned out and, sure enough, there he was, with Simon and Martin Veale. Simon was guarding him pretty carefully and I couldn't really barge in. But afterwards I wrote a little piece about him and T.I.M. Lewis, who'd known him in his Avon and Welsh phases, published it in Mountain ('Molehill'). I felt, very strongly indeed, that Drummond had got a shit deal from the climbing establishment. Yes he'd transgressed - but surely he'd been treated much more harshly than others? Wasn't his real crime not knowing the codes, not fitting in? What feedback I received (no internet, back then) suggested that, with the passing of time, attitudes were mellowing and people were more prepared to give him a chance. Certainly, from then on, he seemed to become more accepted. So, if my little piece was a catalyst, then great. Anyway, for what it's worth, here it is.

Drummond on Censor

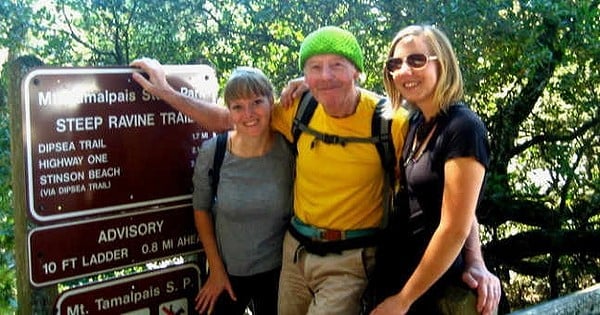

Coming up from the car park, we could discern a trio of people centred on Tippler Direct. Simon at the bottom, Martin on top. And a green figure slowly lumbering through the bulges.

We met them as they came down. A heavy, bear-like man, strangely garbed. Middle-aged, seemingly reticent. (What the hell was I expecting? Some people don't have to appear - or even behave - controversially; they just are.)

His voice. I'd been prepared for that. 'Like an English colonel in the days of the Raj.'

He turned to Censor. Leading, this time. A bad route to choose if you haven't done much climbing of late.

Stepping into the initial scoop. His first runner only ten feet up. Yet still necessary. A few sharp tugs. The ropes confidently clipped. This guy's played before…

Then moving out onto the undercut. Curiously old-fashioned technique. Slowly, with terrible patience, extracting the wrong wire, finding it doesn't fit, fumbling slightly to replace it. Again and again. One brown paw locked on a tiny fingerhold. Not an ounce of uncertainty. Or energy wasted.

"RPs – how interesting. And these gear-loops. Who makes them? Wild Country??"

Back in the scoop. A day sunny but windy. Cold, very cold. Jiggling his hands about in marsupial pockets. A quick, disparaging grin. "It's all right – I'm not having a wank!"

Intermittent chatter with the lads. "An old route? '67? '68?? Impressive for its time…" (Doesn't he realise that it exists courtesy of perhaps his most formidable detractor? Does he care? Does he??)

Then going for it. One brown paw after another. The merest hesitation an indulgence. Up and out, onto the beak, nimbly hopping astride it, up and over, back into the vertical. Where he stops, precariously balances. His runners miles away.

Tentative probes. And he changes position. The moves coming with fluent ease. Yet still alert, cautious. No more runners. Emphasising the second's redundancy.

He pulls over the top. A high, barked laugh. "Come on, Simon, it's your turn now!" At once cajoling and teasing.

We left, to give the man some privacy, chose a route much farther along the escarpment, at times, later in the afternoon, saw his green figure moving slowly among the rocks. And then no more…

Heroes die easily (usually on first acquaintance), the heroic arises sporadically in a man and as suddenly vanishes. There was never much doubt in my mind that Drummond was of truly heroic stature – nor is there now. Just why this should be, I don't honestly know.

It's also my contention that Drummond got a poor deal, a shabby deal from the mandarins of his time, whose petty egos he so loved to irritate. With the benefit of hindsight, is there really that much difference between his ethics and those of, say, Livesey… or even Crew?

Drummond is unique in that he was impeached both for using aid and for cutting it. Certainly, that day on Censor, he used no aid. Just hands and feet and heart. And a unique presence, a charisma which lesser mortals might only emulate. Someone who would stand out in any crowd. For whatever reason.

You can't judge the man by his performance on one route. It's ridiculous. And yet how else can you judge him?

***

Back in 1968, fresh from his successes at Avon and in Wales, Drummond had arrived in Yosemite. He badly wanted to do the North America Wall, then perhaps the most challenging route on El Cap. But he couldn't find anyone with whom to do it. Royal Robbins and Don Lauria had planned a two man approach and they weren't going to change their setup for anyone. In 1971, he tried for the first solo ascent but had to bail. In retrospect, his comments seemed prophetic. "I just think it's too hard for me… It would be too long and too slow and there would therefore be too many uncertainties involved. I just don't feel good about it at all."

A decade later, he returned to the NA wall, once again for the first solo ascent. After 14 days, only three pitches from the summit, he was trapped in a storm. Couldn't go up. Couldn't go down. Knew, from radio contact, that there were other climbers also trapped. Knew it was likely that YOSAR (Yosemite Search and Rescue) would go for them, not him – easier access, more lives to save.

In the event, Werner Braun, for me one of the most impressive people on the planet, was lowered hundreds of feet down El Cap, in dire weather conditions, to reach him. Drummond was saved. Afterwards he wrote an open letter to the Parks Department, remarkable in its honesty. It was as though finally the bubble of bombast had been pierced. Drummond knew he should have died. He knew that his saving had nothing to do with him. When this happens to a person (it's also happened to me), it's impossible not to be deeply aware of it for evermore.

***

Drummond was always about far more than conventional climbing. In 1978, with Colin Rowe, he staged an ascent of Nelson's Column to protest against Barclay Bank's involvement with the apartheid regime in South Africa. Their subsequent trial was at the Old Bailey. Drummond and Rowe were ably defended by John Mortimer and the establishment looked thoroughly ridiculous. It was a re-run of the famous Release trial of a decade previously, where Caroline Coon had faced down a high court judge. When the pair were acquitted of criminal damage to the lightning conductor (yes, it was that silly), Drummond suggested to Rowe that they sing, "For he's a jolly good fellow!" to the judge. This they did. Their performance was much admired by both judge and jury. And the pair were duly fined for contempt of court.

***

Over the next few years, Drummond made further protest climbs on buildings in San Francisco and on the Statue of Liberty in New York. Having thus used climbing as a vehicle for protest (a precursor of the Newbury protestors of the 1990s), Drummond moved on to using it as performance art. (Maybe he always viewed it as performance art?) He clambered around, barefoot, declaiming poetry, on a 22 foot high tripod. No pads back then! Climbing audiences were bemused but nevertheless applauded his chutzpah. With his jaunty beret, Drummond played the part of the (award-winning) bohemian poet, par excellence. With climbing as performance art, he was also perhaps a precursor to Antoine le Menéstrel.

***

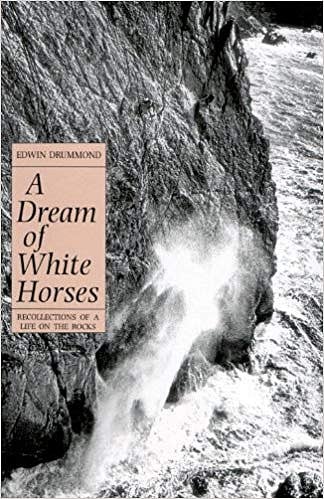

Drummond's old photographer and critic, Ken Wilson, published a collection of his climbing poems and essays, 'A Dream of White Horses: Recollections of a Life on the Rocks'. Reviews were fulsome: 'The most challenging, disturbing and provocative piece of climbing literature I've ever read – the consistent brilliance of the writing is astounding.' (Stuart Pregnall, Climbing magazine). 'An intoxicating mixture: Drummond takes risks as big as he did on his climbs and has the courage to use climbing as a metaphor for wider truths.' (Dave Cook, Mountain magazine.) 'The best climbing book I've ever read.' (Lito Tejada-Flores, High magazine). Controversially it failed to win the Boardman-Tasker award. Shockingly it didn't even make the short-list.

***

In 1985 our very own Chris Craggs bumped into Drummond at Stanage and suggested that climbing the other side of the Archangel arête might be fun. A few days later, Don appeared. It seems to have been Drummond's last important new route in the UK. And it was an affectionate tribute to the then recently deceased Don Whillans, who'd allegedly top-roped Archangel au cheval, with a rubber inner tube between his legs, back in the 1950s! (How, one wondered, had Drummond and Whillans got on? The younger Whillans would surely have gone for a Minks style put-down – if not worse. The older, much more mellow Whillans… who knows?)

Hardcore climber turned psychiatrist (what some of us need?) Grant Farquhar wrote this about Drummond and Don.

His climbs are arguably best viewed as conceptual performance art. For example, Don laybacks the arête of Archangel, facing left, rather than right. This could be described as a post-modern climb, in that it forces one to contemplate what is the definition of a route. After all, it uses the same [hand] holds, just in a different way. If art should provoke, then by that criterion he definitely succeeded.

***

In the 1990s, Drummond attempted a 'Climb for the World' initiative, seemingly based upon the success of 'Live Aid'. Typically he gave it his all. Nevertheless it failed to find the requisite funding. Probably climbing was insufficiently mainstream to attract enough publicity. Very often, highly charismatic figures such as Drummond are slapdash with strategy and hopeless with logistics, although whether this was the case, I simply don't know. Certainly an attempt on Makalu had run into problems. But, then again, many expeditions run into problems.

Perhaps unwisely, Drummond allowed climber and film-maker Simon Beaufoy to make a television documentary about the 'Climb for the World' struggle. It's claimed that no great man is a hero to his valet. Beaufoy's film, the appropriately entitled 'Shattered Dream' proved excruciating watching, contrasting Drummond's undoubted idealism with his troubled family life. Years before, he had made the crucial insight that the ability to focus intensely and selectively during hard climbs (i.e. live in the bubble, exclude thoughts of injury or death) might be exactly what wasn't needed in emotional relationships. Now it was as though his words were coming back to mock him. The implicit soundbite was 'obsessive idealism versus family responsibility'. 'Shattered Dream' was perhaps a precursor of reality television.

I remember talking with companions on the crag at that time, about 'Shattered Dream'. We all viewed it as car-crash television. We readily agreed that Drummond could be maddeningly irritating. But, far more importantly, all of us felt immense sympathy for him, in such difficult circumstances.

***

Drummond first went to live in San Francisco in 1975 and became involved in the poetry world. It's always seemed to me that, in this country, we've always been suspicious of poetry. Certainly, over the last forty years, it's become almost invisible as an art form. But poetry, for me 'the music of words', is a supremely demanding discipline. It's the literary equivalent of bouldering. To excel at poetry demands a much higher technical ability than any other form of writing. Each word must be exquisitely crafted to meld with every other word. Sometimes the finished product may seem deceptively simple, almost artless. The harsh reality is that creating good poetry is immensely difficult. Even the most talented are unlikely to achieve more than a few great poems and a smattering of really good ones in their lifetimes.

As climbers, we've tended to regard Drummond's poetry as simply another whimsical quirk of his psychological makeup – or perhaps an element of a quasi-hipster image. But I can see why Drummond would have devoted some four decades to poetry. As Chaucer cogently noted, 'The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne.'

***

Another aspect of the American period is that it's a big part of his life about which most of us (certainly me) barely know anything. Drummond's immense contribution to British climbing essentially occurred during the years from 1966 to 1975. He seems to have had the enviable ability to climb hard, poorly protected stuff for decades afterwards, whether he was in shape or not. For instance I think he'd done relatively little climbing in the couple of years immediately before that faraway day on Censor.

So this retrospective is tentative, partial. And it's Anglocentric. My guess is that Drummond did a considerable amount of hard climbing in America which we don't know about. And I'd love to know how he was received in the poetry milieu. From my experience, it can be every bit as fractious as the climbing world.

***

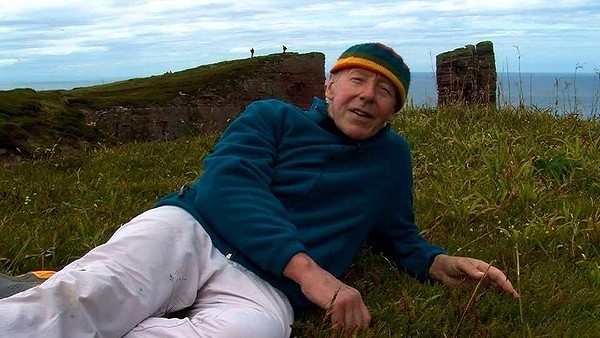

In the 2000s, Drummond was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, bowel cancer and dementia. You think of the ridiculous boldness of leading E5, ground-up, through tottering rubble, with shit protection, on the Long Hope route in 1970. You think of the man who survived 21 days on the Troll Wall. The man who survived 14 days on the North America Wall. How could any of this happen to such a seemingly invincible figure? Yet all of it did. The cruel reality is that, even for the strongest of us, life is often a far more tenuous affair than we care to acknowledge.

Years of suffering followed. I shudder to think what it must have been like for him and his carers. He seems to have borne it with an equanimity we could all strive to emulate.

When he returned to Hoy, the scene of perhaps his greatest triumph, for the filming of the Long Hope route, it was poignant, elegiac, heartbreaking.

***

So how can we do it? How can we possibly sum up such a life of Shakespearean triumph and tragedy? We can't.

Back in 1982 I wrote, 'There was never much doubt in my mind that Drummond was of truly heroic stature – nor is there now. Just why this should be, I don't honestly know.'

Drummond did what all truly great people do: he gave more of himself that the rest of us - far more. He gave more of himself that was sensible, more than was wise. He gave it everything. He didn't know when or where to stop. As he said himself, 'I'm born naïve, so I keep getting into these situations where I'm not quite sure what the code is and really not very interested in it.'

Not knowing the code made him different, probably from very early on in life. It led to social awkwardness, estrangement. It also led to staggering levels of achievement. On so many of his groundbreaking routes, Drummond literally went where nobody had ever dared to go before.

Why did he do it? Climbing is many things to many people. Sure, there are fun-filled days on the rock. But there also those drawn to face the darkness in their souls. For them there can be no compromise. They must seek out their deepest fears and either triumph or perish.

Ed Drummond gave it his all. He couldn't have done any more. Finally he is at peace.

***

Watch the trailer of The Long Hope film documenting Dave MacLeod's direct version of Ed's most famous route.

The Long Hope Trailer with Dave MacLeod from Hot Aches Productions on Vimeo.

- FEATURE: The Corridor: A Review 14 Apr

- ARTICLE: Allan Austin Obituary – A Prophet of Purism 9 Jan

- IN FOCUS: Will Perrin - A Child of Light 14 May, 2024

- IN FOCUS: Custodians of the Stone 5 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: Clean Climbing: The Strength to Dream 31 Oct, 2022

- ARTICLE: Thou Shalt Not Wreck the Place: Climbing, Ecology and Renewal 27 Sep, 2022

- ARTICLE: John Appleby - A Tribute 28 Mar, 2022

- ARTICLE: We Can't Leave Them - Climbing and Humanity 9 Feb, 2022

- ARTICLE: Staying Alive! Climbing and Risk 9 Jun, 2021

- FEATURE: The Stone Children - Cutting Edge Climbing in the 1970s 14 Jan, 2021

Comments

Pitch perfect.

A majestic piece of writing Mick - nicely done!

Chris

A remarkable piece of writing on a remarkable character.

Fabulous piece.

Beautifully written, thankyou Mick.