In this article, climbing coach Robin O'Leary teams up with top physiotherapist Nina Leonfellner to help climbers prevent and cure common imbalances and injuries, thus enabling you to reach your potential without destroying yourself. This article looks at juniors in climbing and how to allow you or your youngsters to become the next Ondra without damaging themselves in the long-term.

As our sport develops, we see more and more emphasis on coaching, training and competitions. For youth climbers, competitions play a huge part in their climbing calendar. From the BMC Youth Climbing Series to the junior bouldering championships, lead climbing championships and the youth opens. This means that children are training far more than they once did and as a result, I wonder how much rest they are getting, how their training is managed and if the next generation are in danger of burning themselves out in a shorter period of time – like we have seen in other competitive sports like gymnastics.

Youngsters are now climbing at a seriously impressive grade, which is great, but often others, with less experience, less conditioning and less hands-on time with a performance coach are trying to emulate what they see our top climbers doing. We hear of poor training techniques and coaching, which in turn may ruin a youth climber's career (in climbing). After all, we are not purely coaching for a season of competitions, but a lifetime of enjoyment.

So, how is it possible to get our youth climbers to achieve these grades whilst maintaining safe practice? Alongside Nina Leonfellner, I have asked for help from some of the world's most recognised youth climbers – Alex Megos, Mirko Caballero, Sierra Blair-Coyle and Britain's Molly Thompson-Smith to answer some of the questions you may have about youth performance climbing.

Nina, how susceptible to injury are younger climbers?

In essence, young children are not at high risk of injuring themselves. If they do become injured, or are experiencing pain, then alarm bells should ring. Young kids should never climb with pain. Normally, this means something is wrong. Kids who reach puberty, and/or are experiencing growth spurts are more at risk of injury, and tendon attachment problems.

Why is this?

Muscles, tendons and ligaments are strong and flexible in a growing child. What is fragile, however, ARE their developing nervous system, bones, joint cartilage, and the bony attachment points of their tendons and ligaments.

Bone growth begins as cartilage, and through cellular change cartilage becomes dense bone once skeletally mature. This happens at the ends of long bones (growth plates), which are found in fingers, arms, legs, spine and pelvis, or within small bones (ossification sites), which are found in the little bones of your wrists, feet and knee caps. There are also growth centers or plates at the attachment points for tendons and ligaments (apophyses). The cartilage of a joint surface also goes through a growth process involving complex active cellular changes. All these growth sites are fragile areas in a child and adolescent, and need to be respected. Insult, or high stress loads to these areas of growth will result in a traumatic, or overuse childhood injury.

Luckily, with conservative treatment and rest from sport or high intensity exercise, these injuries heal well. Rest does not mean complete rest, it means restricted activity. Swimming is a safe alternative because of the non gravity effect on bone, or exercise that is non high impact is normally safe. Best to always see a health professional for any childhood injury advice, treatment and safe alternatives to exercise.

When growing up, are there specific age ranges that become more vulnerable than others?

Yes, adolescent stage is most vulnerable. This is normally where growth spurts and intricate hormonal changes happen. Diet has a profound effect on hormones as well, which complicates this stage. We still don't understand the full picture, and this is not my speciality, but would be happy for other professionals to pipe in and add comments. In all, THE adolescent/puberty stage of development is a complex tricky time where children/teenagers are vulnerable to injury. Growth sites are not stable areas of the body, they are "busy sites" with a lot of neuro and biochemical activity, which are heavily influenced by hormones. Strong muscles, tendons and ligaments forcefully pulling and yanking on these sites can be too much for them. These sites are a youngsters weak point.

Children are developing far quicker today and we are seeing quite a few children in the competition scenes with tape on their fingers and inflamed joints. How/why is this becoming more common?

This should NOT be more common, end of. If this is more common than there is a serious miss-communication amongst the climbing coaches, climbers, parents, setters and medical staff, as well as, regulating bodies.

This is where a medical professional has a duty of care and responsibility to communicate to the climber, parent and coach(es) that this is not acceptable. Swollen finger joints in junior climbers is serious, and should NEVER be over looked. Swollen finger joints can mean an avulsion fracture, or a growth plate fracture, or lesion (trauma or "boney hot spot" to the growth plate, not necessarily a fracture). This can mean the end of a climbing career, long term damage, early Osteoarthritis, and negative psychological effects as a result of all of the above. These juniors need to see a medical professional for treatment and to decide whether an Xray, bone scan, MRI or Ultrasound scan is indicated. Pain lasting longer than a week needs to be investigated with juniors.

Tape can be very useful for minor injuries and for limiting hypermobility (restricting too much movement at a joint). In order for tape to be effective, it needs to be reapplied after 10-20 minutes. I am not convinced that this is happening, nor that the right methods of taping are being used. At the BMC's Climbing Injury Symposium in Sheffield in Nov 2011, the Schoffler's demonstrated appropriate taping techniques, X tape and H tape. I hope that the BMC's new coaching foundation courses are teaching and explaining these techniques. From what I understand they are teaching coaches about junior injuries and giving some guidelines as to what is safe training practice. This is only a very recent thing.

Tape should NOT be used on swollen joints in juniors.

Here is a video demonstrating H-Taping:

Here are a couple of useful links:

These children are only getting injured once they realise they can climb the harder routes/problems. I've heard some people suggesting that we should stop them from progressing so quickly? Are there other methods of avoiding injury?

Juniors who have done gymnastics or dance will always do better than those who did not. They will progress at a faster rate. The same is true for those who have done some other upper body sport to some degree. Some kids are just plain natural climbers and will progress quickly. Kids who start early, before puberty, train well and smartly, have the help of a sensible, encouraging parent and coach, will progress quickly. Throw in some good genetics and the strong collagen gene, and you may have a world class athlete. Why should we stop them? Of course not. Go for it, but get informed, communicate with people who know what they are on about. Communicate with medically sound climbers, educated coaches, local climbing communities, etc.

With juniors everyone must remember that it is the parents, climbing walls and coaches who are ultimately responsible for that young, budding climber's health and well being, and all parties need to be involved at all times, and, communication needs to be free flowing. If a medical professional is involved then they are part of that circle. Each member of that circle needs to know each junior climber inside out. Every individual is different and that is key.

Screening processes help climbers/athletes, coaches, parents and medical staff understand relevant issues about each athlete. Screening is something we do in sport to assess strengths and weaknesses at the start of a season, or when athletes join a squad. Normally the strength and conditioning coach and physiotherapist each conduct a screening which contains tests like: flexibility, hypermobility, balance, stability strength, sport specific strength. Questions will be asked and documented like, what is the junior's sporting background, shoe size, climbing shoe size, and perhaps, ape index. Screening helps coaches, parents and the athletes themselves become more aware of their bodies and introduces them to the concept of how to look after themselves. Screening can also help coaches decide on which of their tests should be avoided with some of their squad, it can flag up issues that are considered injury risk factors. So, screening is aimed at preventing injuries and if an injury occurs then there is a baseline and reference point to work from and towards with each athlete. This is extremely useful for medical professionals, and coaches.

We need to be very careful in devising screening tests, as they are movements that would suggest where a junior might want to better themselves and train for the next screening. This is another reason to conduct screening. To have another test down the line to see improvement in an area that the climber did poorly on, or scored as a "Red flag" on the test. This motivates athletes. If a screening test is borderline safe or something that could potentially hurt or cause repetitive strain, then it should obviously be avoided. We do not want to give the wrong message to our juniors. There is a trend to assess lock offs to failure. There should be a debate as to why this is being screened and what are coaches actually assessing when they assess lock offs, and at what angle are they assessing the lock offs at.

Another way to avoid injury is to learn from ones that have already happened. This is especially relevant in climbing, as there is not a vast amount of research in the area. So every injury should be audited and reflected upon, openly. Every injury should be treated as a case study. This is how we will evolve, learn, and hopefully put things in place to help avoid preventable injuries in the future. Every wall and climbing coach should be documenting injuries and then following them up and reflecting upon them. Asking advice and opinions from anyone who can help assess the whole system around an incident and why/how it came to happen.

Coaches, parents and the climbers themselves can learn the art of "listening" to their bodies. Neil Gresham mentioned very honestly, that listening to his body took time, and came with experience. This is ultimately very true and like anything, experience brings wisdom, and I believe things sometimes happen for a reason, to open our eyes to things. I do think that "listening" to our bodies can be started at a young age, before puberty, which helps this wisdom start early. Communicating like we are now, sharing information with each other, starting injury audits, junior screening and education sessions are all part of that learning and raising awareness process, that can help a young climber learn how to listen to their bodies, and possibly their parents too!

Coaching and training is becoming far more popular in the UK. What are the basic guidelines that we should be considering when approaching youth teams and a varied age range?

To keep things simple, the climbing community needs to appreciate a few things about junior athletes. Juniors can be classified as prepubescent, adolescent and teenage. Each phase has different physiological and psychological factors to consider like fragile bones, hormonal influences, immature emotions, and immature mental coping and assimilating strategies. So, getting to know each junior very well is key, from a climbing performance, physical, social, mental and emotional point of view. Working closely with their parents to help have insight in all these avenues is key, and that is sometimes the tricky part. Either the athlete themselves, or the parents, may not be on board with this. That has to be respected, but it should be made aware, that this could possibly limit the potential of that climber.

I think that some sort of screening process should be conducted, preferably with a physio and a strength and conditioning coach with the climbing coaches. This happens in most sport, so it should happen in climbing too. Within the screening process hypermobility (slack joints) should be assessed. This can easily be tested by anyone. The Beighton Score, it is a very easy testing measure that anyone can do. Any junior who is hypermobile will need to do more strength and stability work alongside their climbing, as well as, possibly use some taping techniques to restrict elbow and finger hyper-extension.

Juniors tend to be very flexible, so assessing strength and stability in a way that that also assess flexibility will tell you more than pure passive muscle flexibility tests.

Here are some tests that I use:

(In these photos, the "subjects" are wearing t-shirts. For my tests I usually seek the parents/guardians' permission for boys to be topless and for girls to wear a sports bra to accurately assess shoulder blades, spine and pelvis)

Straight-armed plank

Superman Plank

Standing active leg raise

(Scored red flag due to the raised leg not being 90 degrees, the lower leg not being straight and the hips slouching forward)

Pull-ups

Fingerboard - dead hang – elbow and finger position

Press up

Side plank

Straight arm leg raises (L Hang)

Single leg squat

Single leg bridge

Injury auditing and questionnaires should be used within squads. Growth and height should be monitored as well.

I am all for the competition scene and believe it is one of the healthiest developments for our sport, but when you hear about children using weights and locking-off to failure you have to reconsider the concept. What is your advice to those U16s experimenting with weight vests, campusing, fingerboards and locking-off?

As I mentioned earlier, coaches need to be very careful in what they advise and use as strength tests, to not give the wrong impression on training.

Campusing is risky for U16's because of the shock loading on fragile growing bones. It is safer to say avoid it. If a young climber has been training and climbing since way before puberty, is showing signs of having the "good collagen gene", has been doing feet on campus rung hangs and reaches, then feet off hangs, reaches and pull ups, and they are doing their core stability training, pressing exercises, and they have good coaching on how to campus, and are not crimping on the rungs, then there could be some negotiations. At the end of the day, each individual is different and some are pure athletes with raw talent, so why stop them. We just need to be aware of the effects of what coaches and elite climbers are prescribing as training advice.

Campusing with a weight belt is extremely risky, I would never recommend this as a physiotherapist for a junior climber. The potential load applied onto soft, growing bones will be far greater than body weight. This is asking for trouble in my opinion. I have already treated a junior who injured her elbows after this sort of training. The extra weight on small rungs increases the risk of overload on junior bones and their soft tissue.

Climbing with a weight vest I think is fine, as long as, a base strength has been coached first, as well as, climbing technique, preferably with video analysis. There is no point in training poor technique issues, especially with weight added to the equation!

I have concerns about testing and training lock offs. Deep lock offs are strenuous as they are at end of range elbow flexion, where the joint, tendons and nerves are maximally stretched and compressed. This loads the bony tendon attachments more than mid range. So, deep lock offs are risky there is no question. Assessing them informally, with no weight in a training session is fine, however, including them in a screening or testing environment, I feel is very dangerous. It gives the junior the impression this is something to work on, which if they do, they are at risk of overloading their elbows. Also, I am not sure emphasising lock offs, especially deep lock offs, is conducive to promoting good climbing technique. There are many elite climbers that back me up on this. Occasionally you have to hold a deep lock off, but not enough to repetitively train it. Not in a junior career. It is debatable whether or not to assess mid range lock offs (lock offs at 90 degrees). Mid range is safer than end of range, however, I am interested in what coaches are actually assessing when they do this. Is it purely time? What would be better, is to assess how they hold the position: ex:, with their necks?; are they using their lats well?; what position are their shoulders in?; what happens to their form when they fail? I hope this is being documented and assessed, rather than just time to failure. Again, this is where screening with S&C coaches and physios can help.

Robin: I agree entirely and would like anyone who does do this training/coaching to contact us to discuss in more detail. IF you are a coach and train youth climbers, be it a single child or a whole squad, I think it is essential that you start a season with pre-season conditioning and a screening with a specific S&C coach, a recommended physiotherapist (with strong youth experience) and a nutritionist whilst documenting all of your findings. This should be followed with stages of re-assessment.

We have some remarkably strong children coming up through the ranks and it is our duty as a community to ensure that they have a lifetime of climbing – not just one competition season.

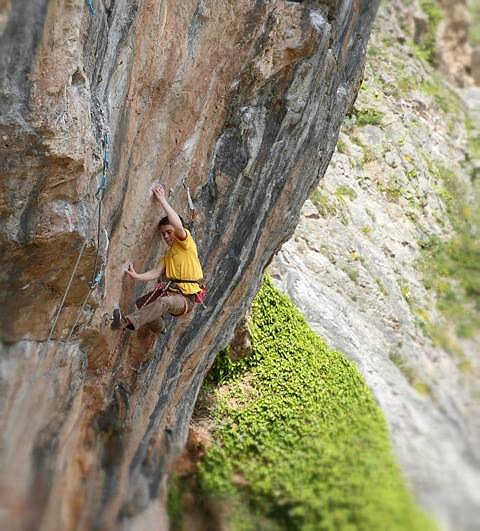

Following on from Nina's advise, I thought it would be interesting to speak to some other climbers about training and youth climbing starting with Neil Gresham who recently completed Welcome to Tijuana, 8c, in Rodellar.

Neil, over the years you have been involved with coaching many of the top names in British climbing; from Leah Crane and Kitty Wallace to Tyler Landman. When operating at such a high level, did you find that you had to limit what you could allow these guys to do? (If so, in what way?)

Each case is different, but yes of course you are constantly monitoring the workload. It can sometimes be hard to convince them to rest or do easy sessions, but then I still find it hard to do these things myself, such is the nature of climbing. Youngsters with a high talent level and superior genetics may be able to cope with a higher workload than protocol dictates, but you have to know your subject inside-out and work with them closely over a long period to be able to determine this. Clearly you will constantly be teasing the line and it's very important to keep the parents in the loop, so they understand the process. To get a youngster on a podium, there will always be risks, but these need to be managed in a multi-disciplinary team environment. I am proud that no young climber I've worked with has ever been injured under my watch. The career-ending injury that Kitty Wallace suffered at the hands of a different coach is a tragic example of what happens if caution is thrown to the wind. I can't stress enough how one wrong move can break a young climber at this level. On a different note, as much as I'd love to take credit for Tyler Landman's prowess, I should point out that I didn't officially 'coach' him and was more his training partner. He was a law unto himself and it used to feel like he was coaching me much of the time!

Today's competition calendar is busier than a London socialite's party diary; we are seeing many children finish one competition and jump straight back into training so that they perform for the next one. What words of advice can you offer to the competition climber of today? Should they try and experience every competition, or pick and choose wisely?

Of course, they have to pick their battles. It's a simple equation: the more comps you try to do, the lower on average your performance will be and the more you risk injury. By consciously allowing your performance to drop back down, you can factor-in vital periods of recovery and then peak for the comps when you really want to do well. Most top climbers you speak to will consciously do this, without even questioning it. They know from experience what happens when you refuse to drop the ball.

I am sure you have seen younger climbers experimenting with weight training. I have heard you regret the amount of weight training you did when you were younger? (Is this true?)

Absolutely. I'd be as good as Steve McClure if I didn't weigh twice as much as him! Ha ha, perhaps not quite. I'd advise all climbers to stay off the weights unless they have a serious structural weaknesses in their physique. I over-did weight training purely because it was the only form of training I had access to as a teenager and there was no information around at the time. In the mid 80s there were hardly any climbing walls and those that existed were vertical, with half-bricks sticking out for holds! There were no training articles or internet so you had to make it up as you went along. This was one of the many reasons why I got into coaching and writing training articles: I wanted to facilitate an exchange of information and prevent climbers from making the obvious mistakes.

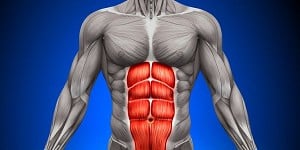

As discussed with Nina, our antagonist/strength and conditioning training is vital in avoiding injury, but we are seeing some very overdeveloped children today. Do you think that this is true? And what can be done to prevent it?

So much more is understood about the affects of climbing on the body these days. Modern elite climbers can cope with a higher workload, partly because training facilities are more user-friendly and also because they understand the importance of balancing the body. By strengthening the opposition muscles, you can prevent muscular imbalances (which often lead to tendonitis or similar injuries) and also in an indirect way you will actually promote strength in the muscles you need for climbing. If a climber can't be bothered to do 3 sets of 20 press-ups and reverse wrist curls, 2 or 3 times a week then they can't really complain if they get injured.

If the sport continues as it is, do you think we will be in danger of seeing climbing becoming more like gymnastics whereby the age for a competition climber becomes lower and lower and the "competitive life" of that climber will become much smaller, or do you think our sport is too diverse for this?

It would seem that competitions have already gone that way. It's not just about physiology, but for some reason, overwhelmingly, the youth seem more motivated to compete than older folk. But the great news about climbing is that it's not all about comps and older exponents can bring a whole variety of skills to the table that can compensate for the ageing process. I know I'm not as strong as I was in my twenties, but I'm certainly fitter and a better climber overall. But the biggest part is that I don't get injured anything like as much as I did when I was young because I've learnt to listen to my body. This is of course, something we are told to do when we're young, but we don't have a clue what it means!

Robin: Neil makes a good point here and I thought it would be best to speak to some of the best youth climbers that exist today, starting with the youngest, Mirko Caballero. For those that do not know, Mirko is 13 and has bouldered V14 (this past weekend) and topped 8c+. He is right in the middle of his adolescent years and the questions have to be asked about his training?

Mirko, firstly, can we get a bit of history – how long have you been climbing for?

My parents and siblings all climbed before I was even born, so I hung out at crags and the gym when I was a few months old, and started climbing very early. I remember getting serious about climbing and competitions when I was 6 years old. Actually, my recent USA Bouldering Nationals in Feb-Mar was my 7th participation in a row at that competition...

Do you follow any training programmes- how long would you say you have trained for climbing?

As I said, I started "training" when I was 6 years old, but my Dad is my coach and he only wanted me to climb and have fun. He always said climb hard, climb a lot, but mostly just have fun. So that's what I did until last year. Two years ago, I joined the Zero Gravity Team, and I started doing a bit more detailed training with them, although only once or twice a week. The rest of the time, I still trained with my Dad. Last year, as I started to grow fast, my Dad said I should start following a more formal training programme that included power, finger strength, but also non-climbing muscles to balance out my training. He took advice from Teamof2Training (Justen Sjong and Kris Peters) for that. Justen helps me with technique, sequencing and mental focus, and Kris is really good at conditioning, and power training.

Has your training ever been limited? Were you told not to campus and fingerboard for example? Do you do this now?

Yes, until spring 2013, my Dad would not let me work on the fingerboard. He let me do some campusing while bouldering, but no too much... When he sees beginner or intermediate climbers working on the finger board, he tells them that they shouldn't do that. He thinks that you get much more value from just climbing, learning moves, body position and technique, with less risk of injury. But now that I've grown a lot, he said that I needed to keep up with my size and weight, and so I now have regular work outs on the finger board. I mostly work on hangs and lock-offs. I also do some dynamic up campus moves. My Dad doesn't like me to do dynamic down moves, like dropping down rungs. He thinks it's an easy way to get hurt, and doesn't really add that much value.

Have you ever had any injuries?

I've had a little problem with my shoulder rotator cuff, but the doctor said that was probably due to the hyper flexibility shoulder work that I did when I was competing in gymnastics. he said it was pretty common. I did some shoulder training with rubber bands, and it got better really quickly.

Last year I chipped a piece of bone on a finger, but it wasn't from pulling. I actually broke a piece of bone attached to the Extensor tendon (the one that straightens your finger), and the doctor thinks it came from crushing the top of my finger against the rock while camming my knuckle against the rock in a small pocket. I stopped climbing for a few weeks, and it's all good now.

Other than that, I sometimes have sore fingers, like when I worked Meadowlark non-stop for a few days constantly repeating the same crimpy moves. But I just stopped for 3-4 days, and it went away completely.

Considering you are going from strength to strength and in the middle of this delicate age, what advice can you give to climbers aspiring to get to your level?

I think what my Dad told me works great! I climb a lot, about 3 times a week for 3 hours each in the gym, and I climb outdoors almost every weekend and vacation. I like bouldering, and that's how I get my power, but I also mix it up with sport climbing which requires more planning, sequencing, and mental focus. There are a lot of climbers in my gym that are really strong, sometimes stronger than me, but I can still climb better because I work on technique, problem solving and sequencing, and I can climb on any type of holds. We try to go to lots of different crags with different rock requiring different techniques. So I got better at crimps, pockets and footwork in Smith Rock. Castle Rock forced me to work on slopers. Red River Gorge is all about power endurance. Trad in Yosemite forced me to learn about cracks and off-widths. My point is that climbing in different areas forces me to expand my moves, and forces me to get better at things where I feel weak. My Dad said that what worked for him when he was competing in acrobatics was "Maximise your strengths, and minimise your weaknesses". So I'm trying to do that. When I can't do a move, I first try to find a different beta that works for me, but then I come back and try to also make it the way I couldn't do the move.

Do you do a lot of strength and conditioning training and any other disciplines?

I used to compete in gymnastics, until I had to choose between gymnastics and climbing. It gave me a huge advantage on other climbers my age because I had more core, I was more flexible, and I had stronger shoulders.

I also enjoyed running a lot, and I think it helps me with endurance.

I now do very specific conditioning training including running, finger board, power, core, and working non-climbing muscle groups to complement and balance out... For example my Mom worries about seeing all those climbers that are hunched over, so Kris Peters makes me work on muscle groups that help straighten out my back...

Anything else you would like to add?

I'm really driven and I really like competing, but I think I would burn out if training in the gym and competing was my only climbing activity. I see some of my friends do that, and they're happy when the do well, and sad when they don't and just train from comp to comp. For me climbing outdoors is much more important, and I'm really happy every time I'm outside. I still like climbing hard and pushing my limits, but it's like I compete against myself, trying to get better all the time, but without the stress of competition. I like competing and I think I will keep on doing it, but climbing outdoors is what keeps me psyched no matter what.

Robin: Molly Thompson-Smith is the best youth competitor that is currently representing Britain. Molly is climbing and competing at the top of her game, let's see what her secrets are.

Molly, you have been climbing for quite some time now haven't you?

I had my 7th birthday party at the Westway Sports Centre and decided to try out climbing. It turned out I loved it and a year later I joined their club. So now I've been climbing for 8 years and still enjoy it like I did my first time.

What age did you start training?

I competed in my first competition (BMC YCS nowadays) at the age of 8 (only a term after I started club climbing) and that was when I joined the Westway Climbing Squad. I would climb 2 times a week with a coach and other climbers. Some could say that that was when I started training but I believe I didn't start training properly until I reached the age of 12 when I tried out for the British Team and set my goals higher, aiming for national titles.

Have you ever been injured?

I have been fortunate enough to have no serious injuries that have put me out of the game for a long period of time. I have had the odd tweak now and then in the fingers but nothing has ever been serious (touch wood!). However, I do have a problem with my wrists that myself and Rob are unsure of; lt's sporadic and is always on a different wrist each time. At the moment, this isn't a major problem.

What do you think the key behind safe training is?

I think the key is to understand and listen to your body. If something hurts, stop. There is no point in pushing that bit too far and putting yourself 2 steps back when you were trying to jump 2 steps forwards. Also, know your limits - don't go crazy trying to impress someone and don't be afraid to tell your coach or friend you don't want to do something. Its important to be an athlete and look after yourself; you are responsible for yourself and your well being.

Robin: From a British female in the limelight to an American, Sierra Blair-Coyle. Sierra has been known for being the youngest competitor in the ABS Nationals in the past, we asked her two questions about how to whether youth climbers should be stopped from training/progressing to limit injury?

Do you believe that we (as coaches) should limit the progression of enthusiastic and strong youth climbers in order to prevent injuries?

If a youth climber is motivated to climb and train, they should not be limited. Preventative injury maintenance is important and can accompany any training program.

Having climbed and having been coached throughout your teens, do you have any great tips to young climbers to reduce their chances of sustaining severe injuries?

Preventative injury maintenance is crucial to preventing injuries! Having well-balanced muscles helps to drastically reduce injuries. Always listen to your body and climb all types of problems so you don't overwhelm one certain body part. On a simpler note, always make sure your crash pad is in the right spot so you don't sprain an ankle.

Robin: Finally it bring us to the man of the moment, Alex Megos!

After being the first person to onsight 9a at just 19 years old Alex has made a name for himself on the rock and in competition climbing.

Alex, you were the first climber to onsight 9a and you did this at the age of 19. Going on this, you must have been climbing from a fairly young age and training hard too? Have you ever suffered from any long-term injury?

I started climbing when I was 5, so you could probably say I started at a fairly young age, yes. Real training I started a bit later though, when I was around the age of 12/13. I am very lucky, I have never had any kind of injury which forced me to rest! Actually I never had any kind of injury!

Is there any sort of training that you avoided or were told to avoid as a youth climber/competitor?

Yes, there was some training which we avoided with my trainers. Especially the campus board at a young age. I never did anything on the campus board until now. Also the finger board was one thing, which we didn't use in younger years. We had more a focus on the steady progress and built up a lot of core strength, which we using various ring exercises and other training tools.

What words of wisdom do you have to any budding youth climber or authoritative coach when approaching competitive climbing at a young age? Are there any dos and don'ts that you stuck by?

Ah yes, I have a some top tips that I can pass on...

First of all, the FUN is the most important thing! Especially when it comes to training with the youth! The trainer/coach should keep an eye on that every time. It's no use to do any exercise which the athlete doesn't enjoy, because sooner or later he will loose his motivation and fun for climbing.

That leads me to the next point, motivation! Motivation is definitely the most important factor when it comes to progress in climbing. But it has to be used with the brain! So no brainless hardcore training just to feel as destroyed as possible. Use the energy you have in a smart way to do exercise which will really help you to progress. That's also part of the work of a trainer/coach. He/she has to show the athlete how to train smart.

And in general, the athlete and the trainer should have a good relationship to each other. So the trainer has not just the role of training the athlete, but should also support him in any part of life (school problems), however, that does not mean the trainer should do maths homework with the athlete! It's more like a support system in a way - the athlete has somebody to talk with (apart from the parents) about his problems and thoughts.

Robin: So Nina, this is very interesting. Here we have a collective of the best youth climbers in the world and it seems they nearly all fingerboard and campus. They were told to refrain in the younger years, but as of 13-15 given the all-clear? Is this due to the ages that they started climbing? Did their bodies adapt to the sport earlier on and therefore the rules are different?

I think the best answer to this is that yes they have started good, safe training BEFORE puberty, by as I mentioned, some good coaches, luckily one was a parent. Supportive, not pushy and somewhat well informed. I think whoever is coaching a pre-adolescent child MUST get well informed by medical staff and climbing coaches. These young climbers are most likely the ones I mentioned in an answer above. They have trained mainly for fun, with some healthy encouragement, healthy pressure on themselves and from their coaches/parents, they actually have coaches and parents that are present, people who know them inside out and help guide their training, nutrition and social, life and sport psychology along the way. They most likely have what we call the "good collagen gene" as well! Their collagen (building block of all tissue) must be adaptive and strong, which helps make an outstanding athlete.

What will be interesting is to see what happens throughout puberty and teenage years..... As I mentioned these are 2 very different stages of development with more complicated processes going on. I have to say to them to be careful with campusing, especially weighted campusing. If they have a base strength to be able to boulder V13 then they can campus! But if they add weight to the equation, like a weight belt/vest, on a day that they are a bit tired and going through a growth spurt, then the risk of injury is higher. So, my job is to help inform parents, climbers and coaches of injury risk factors. Not to stop young athletes from doing the sport they love. I really want young climbers to keep climbing and I want more young people climbing. But we need to climb and train smartly!

If you have any questions about this topic, and more information on Robin O'Leary - please visit his website

Check out Nina's website for more information on her treatments and how you can book a session.

More info on Nina Leonfellner: After qualifying as a Physiotherapist in 1999 from McGill University in Montreal, Canada, Nina has been treating sport and musculoskeletal injuries in the private sector ever since. Nina has been a dedicated rock climber since 2000, and has treated, climbed and worked with some of Britain's elite rock climbers, such as, Hazel Findlay, Ben West, Neil Gresham, Tim Emmett, Charlie Woodburn and Chris Savage. Nina writes articles in CLIMB magazine, as well as, teaches an Injury Prevention Module on Neil Gresham's Masterclass Coaching Course. Nina is also a lead clinician for EIS and High Performance Squad athletes at Bristol University.

Comments