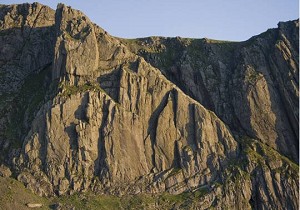

Many of the tales imbedded within climbing folk-law serve to paint a picture that there is a fine line between being a focussed top-level performer and an obsessive lunatic. Extreme dieting and training regimes are common tactics, jobs have been quitted and relationships put on the line. A glint will appear in the eye when 'that' particular climb is mentioned and, for me, that climb is undoubtedly a certain route in North Wales on a crag called Clogwyn d'ur arddu.

I have written before about my ascent of Indian Face, which turned out to be the mother of all epics. For several days afterwards, my sleep was disturbed by flashbacks, and one night I decided to burn the midnight oil in an attempt to lay things to rest. The resulting piece that I wrote seemed to serve its purpose in curing my insomnia and at the time, I felt no need to inscribe anything about the extraordinary chain of events that led up to me trying the route in the first place. Yet looking back, this is perhaps the strangest part. How can a young sport climber with such a limp trad CV suffer such delusions of grandeur? Surely a fit of inexplicable madness was responsible, or a self-destruct button waiting to be pressed? In fact, it was neither of those things, but more worryingly, a slow and gradual detachment from reality as I became seduced by my ultimate climbing fantasy. Fuelled with youthful naivety, I managed to build a castle of self-justification that was just waiting to come crashing down on it's paper-thin foundations! But having lived to tell the tale of Indian Face, I based my preparation for all subsequent ascents on the chilling lessons I learned that day up on Cloggy.

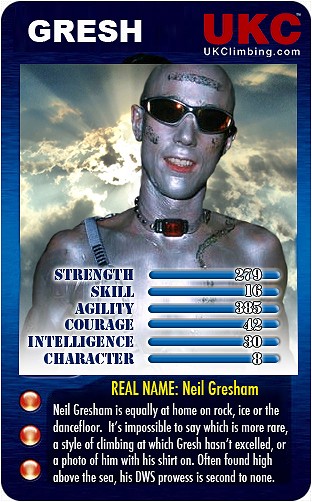

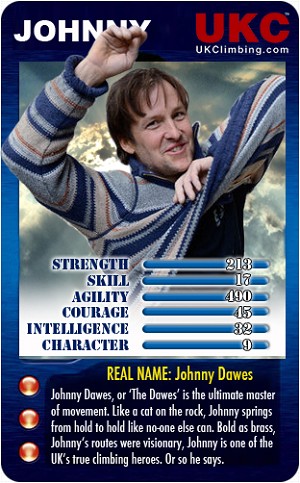

First some background. Indian Face was first climbed by the enigmatic, Johnny Dawes in 1986 when he was at the height of his creative powers. This monolithic climb epitomised everything that British climbers wanted their hardest route to stand for. A perfect line in a remote setting, steeped in history and heart-stoppingly bold (to the point that even Dawes seemed to return from battle a changed man). The slab gets steeper, the gear gets worse, the line becomes inescapable and you are left to confront the hardest moves at the very end of the pitch. To make matters worse, there is a large foothold (known as the 'rest ledge') just before the crux, and Dawes reckoned that this actually made the route harder, simply because it gave you an opportunity to go to pieces! For ten years this climb gave a defiant fingers-up to any prospective challengers. That was until a rainy day in the Spring of '94, when a chance meeting between myself and 'headpoint guru', Nick Dixon, turned my entire world upside down.

Nick burst into the outdoor shop in Betws y Coed where I was working, and started gesticulating about the Indian Face like some crazed religious fanatic. His ranting would probably have prompted most folk to move away, but for some reason, I was captivated. At the time, I was several months into a forced sabbatical from sport climbing that had been brought on by a bout of elbow tendonitis. I was generally feeling a bit down on my luck and so it was good to dial into some fresh inspiration, albeit something this far-fetched. "It's just a climb at the end of the day!" Nick declared, "It's got holds and it can be done!" Surely no one was allowed to talk like that about Indian Face? He seemed to be breaking a major taboo here, but I admired the fact that he was even considering an attempt and ended up pledging some belay support. At that stage the idea of stepping on to the route didn't even enter my head and I was simply keen to pay homage.

A few days later I found myself stood on the ledge at the top of Great Wall making every attempt not to be over-awed by my surroundings. Nick fixed the top-rope and abseiled down first. "Not much gear here,' he muttered with masterful understatement. I followed him down, barely daring to touch anything like a young child in a museum full of priceless artifacts. Nick couldn't tie in fast enough - he put in an impressive performance and flashed it by the skin of his teeth. "Over to you now!" he said. I hadn't even considered having a go until that moment. Surely it isn't tennis to top-rope a route like this if you have neither the intention nor the ability to lead it? I declined at first, but intrigue soon got the better of me and I somehow managed to slap, sketch and barn-door my way to the top. The turning point came as I lowered down and Nick turned to me with a devilish grin: "If you can flash it on a top-rope then it's definitely on for the lead!" Of course, my initial reaction was to laugh, but Nick wouldn't let it go. "If you can climb 8b sport routes then you've got the physical buffer, and if you can do ice routes on the Ben then you know how it feels to have no gear!" It made sense on paper but the reality seemed a million miles away.

From this point onwards, Indian Face was the only thing I could think about. It was the last thing to fade from my mind as I tried to sleep and the first to torment me when I awoke in the morning. I was trapped on a never-ending rollercoaster of either doing the route or not doing it. The troughs of 'not doing it' made my heart sink with depression, but the peaks of courting the idea made me sick to the stomach. In the end I realised that the only way to break the cycle was to do it and from that point onwards my destiny was mapped out. But at least I wasn't alone. In a twisted game of role-play, Nick Dixon had become my new mentor and he was more than happy to pass on every tip and trick in the book to help me keep my appointment! His first advice: "Don't over-practice it, or you'll get too locked into a sequence and won't be able to freestyle, if it goes pear on lead". The thought of 'free-styling' up there was incomprehensible to me, so I listened carefully. 'Three or four times will be enough for me, but it's your call!" said Nick. I settled for four and then top-roped it a fifth time for good luck!

As the day drew closer, I found myself agonising more and more about how it would feel to lead the route. Had I merely lulled myself into the ultimate sense of security with all this top-roping malarkey? I wasn't sure if I should ask Nick what he intended to do if it did go completely 'pear' up there, as perhaps that was something that even he would prefer to sweep under the carpet. But sure enough, I asked anyway! "Use the 'Catastrophe Cusp' method", was my guru's response! Nick coined many of his methods from Zen practice as well as cutting-edge research into sports psychology. The name of this one sounded somewhat fitting and I was keen to hear more. "The idea is that once you reach the point when you can't get any more scared, then the only way from that point is up! The secret is not to fight it. Acknowledge peak fear, breath deeply, re-set and then slowly start to recover." This sounded all well and good for Olympic finalists, but I must admit that I was concerned it might fall a little short of the mark for someone who was about to hit a scree slope from fourty metres!

But again, Nick had the answer; "Indian Face is nothing compared to the 'T ceremony'!" he said with wild eyes. "The Samurai warriors had to prepare themselves to engage in a duel with real swords as part of their inauguration, knowing full well that one of them would definitely die!" If he was saying this to make me feel better then it wasn't having the desired affect, but I was keen to hear more nonetheless. "Beginners mind!" said Nick. "Live in the present. Throw away all your pre-conceptions and step into the arena, thinking only about what you can give to your performance and not what you expect in return". I had been struggling to follow Nick up to this point, but then suddenly the penny dropped. In the past I had accrued a great deal of selfish and destructive energy whilst sport climbing. I'd become so pre-occupied with my ego and the results I wanted, that I'd lost sight of my original motives for taking up climbing. But this time I would have no choice but to change my tune. I realised you can't want to 'have done' a climb like Indian Face; you have to want 'to do it'. Not dread it. Live it. Be there and feel it. Live to learn from it or don't as the case may be. Or as Nick's Zen mentor, Shunryu Suzuki said, 'Give yourself readily to the flames without holding back the tiniest trace'.

On this advice, Nick and I went forward to make the second and third ascents of Indian Face respectively within a few days of each other, like partners signed in blood. Needless to say, it did all go massively 'pear' for me on the lead, and the 'Beginners mind' didn't quite work the way Nick had intended. I started to wobble and shake like a beginner, and I must have dodged the blade of that Samurai sword by a hair's breadth. It was far and away my closest ever shave, and I still look back on it with a mixture of pride tempered with disgust. I should clarify that I learned in hindsight that all Nick's advice was absolutely airtight; I just didn't have the experience or the maturity to carry it out. In addition, there were a few other notable 'home-made' tricks and tactics that I conducted for that route; such as the training program which involved a daily 6 mile run on my tip-toes followed by 500 calf-raises. Then there were the crazy 'Kendo' shoes, that I crammed my feet into, three sizes too small, in hope that the pain would distract me from the fear. I also decided to wear nothing other than a pair of lycra shorts on the climb, because in my deluded state, I had become convinced that any other type of clothing might snag and upset my balance! Better still, I had become ruthlessly superstitious about an incongruous whispery, mustache that I had half-cultivated. I made a pact that I wouldn't shave it off until I'd done the route in order to strengthen the incentive! But the final words of wisdom in this saga must come from Mr Dawes, the master himself. Prior to my ascent I had been incredulous that Johnny had managed to summon the psyche to step off that infamous rest ledge so I asked him to reveal how he did it. "Oh, that part was easy in the end", he said, "I knew I would only be back, so I thought I may as well get it over with!" Perhaps when you are that committed to doing something, it really is as simple as that.

Footnote. As a mark or respect for the climb, Neil and Nick Dixon opted not to set-up any staged photos on the Indian Face

Comments