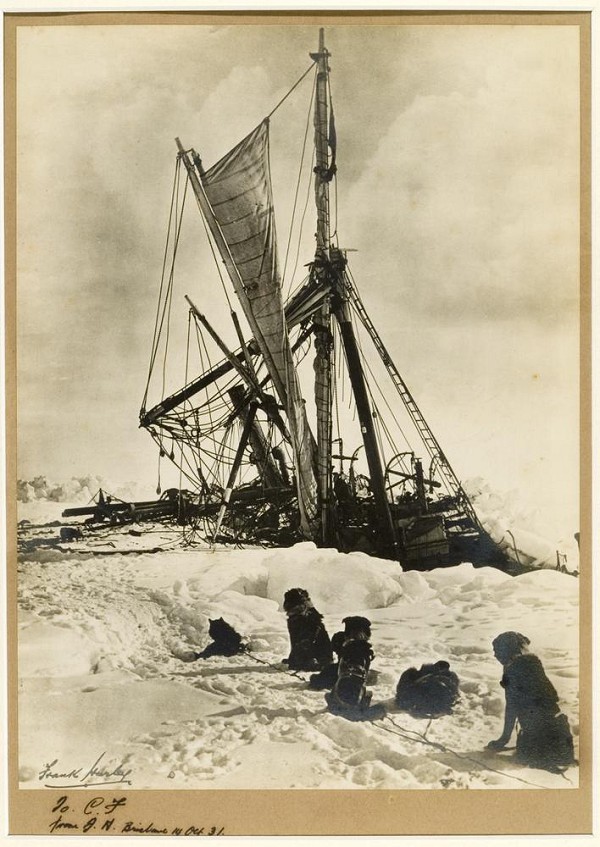

This year is the centenary of Ernest Shackleton's death, aged 47, at the start of what would have been his third Antarctic jaunt. As an expedition reports finding the wreck of Shackleton's lost ship Endurance, complete with remarkable photos, Ronald Turnbull looks back at this almost pathologically understated account of one of the worst journeys in history, a tale of squalor, fortitude, and upper lips as stiff as the frozen sea.

There's a couple of ways that 'South' by Ernest Shackleton doesn't quite fit the category of mountain literature. For a start, few mountains. Then there's the way that the first year and a half of the adventure journey involve a total walking distance of – ummm – 7 1/2 miles. But there's one aspect of outdoor adventure that Shackleton's expedition excels in: that of making any mere mountain climb seem rather pathetic and tame.

Any worthwhile adventure has to be a bit uncomfortable. Some more than others. The ice-cave on Denali where you fester for a week or two waiting for the gap in the blizzard, killing time in the cave with walls made of frozen human excrement, I'll admit to being too wimpy for that one. But the most adventurous adventure of all time, in terms of discomfort, danger, mental strain and pure squalor, extended over two full years? It has to be the Antarctic expedition of 1914-16 led by Sir Ernest Shackleton.

It wasn't just the upper lips that were stiff – absolutely everything being frozen for hundreds of miles in all directions

Coming four years after Scott's trip to the South Pole, the plan was the first full coast-to-coast crossing of the Antarctic continent. And it failed. Failed spectacularly, even within the British tradition of heroic failure. At no point did they even set foot on the Antarctic mainland. Through the early months of 1915 they sailed south through a maze of ice, ice that piled and crumpled and occasionally moved apart to let the ship grab a few more southward miles. Still many miles from the shore the ship froze in, and they sat in it through the long darkness of the Antarctic winter.

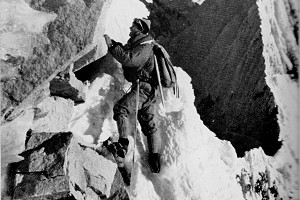

In spring, the shifting of the ice crushed their ship and sank it. They moved onto the ice. Where they lay wondering whether an intelligent killer whale was going to suddenly come up through the ice under their sleeping bag. After three months of this, the ice broke up under their camp. They rowed in the open boats for 108 hours to reach the uninhabited Elephant Island. They had faced boredom and saltwater boils; famine and frostbite; sleeplessness and seasickness and sheer, simple squalor, for over a year and a half. They now embarked on a sixteen day boat journey of outstanding difficulty and danger across the Southern Ocean, before the 36 hour walk over the 1200m-high, glaciated, snowbound and unexplored mountains of South Georgia.

Any worthwhile adventure has to be a bit uncomfortable. Some more than others

So why do I find myself reading 'South' as a treatise in sociology?

There's the intriguing question of why should men (the expedition was, of course, all men) voluntarily accept such a high level of misery and danger, extending through two so-called summers and the long, dark winter between, totally alone and with no communication with the outside world? How did they adapt, how did they cope? There's an intriguing hint in Chapter V, the men now camped on the ice, on short rations, with the prospect of dragging their three lifeboats across the mangled icefield for weeks or months. At this moment Shackleton issues a single full meal including luxuries like flour and peas rather than yet another penguin. 'It is just like school days over again, and very jolly it is too!' These are all public schoolboys, regressing to a simpler stage of life, and a damp tent on an icefloe isn't really all that different from Dormy 6B at Dotheboys Hall.

Then, there's the very period British attitude of mock-modesty and understatement. It wasn't just the upper lips that were stiff – absolutely everything being frozen for hundreds of miles in all directions. The only emotion on show is a certain understated patriotism, and not even much of that as everybody already knows that Britain is Top Nation.

I'm a twentieth-century bloke myself, and I don't really go for the expedition accounts of today where they wave their emotions overhead like a flag ripped apart by the wind. I like my adventurers to show, but not to tell.

But Shackleton takes this self-restraint to the extreme. The two months camped in a blizzard alongside their damaged ship, on an icefloe gradually cracking apart, living on seal and penguin and reading the same two pages of the Encyclopaedia Britannica: 'Our time at Ocean Camp had not been one of unalloyed bliss.' When their ship, crushed by the ice, finally sinks: 'I doubt if there was one among us who did not feel some personal emotion….' But perhaps that's okay, as it's a boat rather than a fellow human being. 'It will be sad if such a brave little craft should be finally crushed in the remorseless, slowly strangling grip of the Weddell pack [ice], after ten months of the bravest and most gallant fight ever put up by a ship."

So what does it feel like, when you've killed your dog team and eaten it? And reached solid ground, only to find it not all that solid after all as you're sleeping on a slurry of half melted snow and penguin poo? And after all that, you set out in an open boat – a 20-foot lifeboat powered by oars and a small sail – through the world's harshest sea conditions for a voyage of 800 miles.

Not nasty enough for you? Well then, imagine not setting off in the open boat. Imagine being left behind on a beach mostly covered in ice, wondering how many months or years before the rescuers would come, or maybe they never would. (And if they did, would it be appropriate to give three cheers? Or would a simple handshake be the thing?)

At this point, we do discover a little about their states of mind. The cook loses the use of his fingers, and to recruit a new one Shackleton chooses 'one of the men who had expressed a desire to lie down and die'.

So one member of the expedition, anyway, was reacting like a normal human being.

- August 1914: leave UK

- Dec 1914 dep S Georgia

- Ocean camp: 3 months

- 21 Nov 1915 ship sinks

- 12 Dec 1915 drifted back to same latitude as 3 Jan 1915

- Dec 23-28 1915 dragging boats over broken ice: 7 1/2 miles

- Jan – Mar 1916: Patience Camp on sea ice

- 2 April 1916: eat last of the dogs

- 7 April 1916: ice floe breaks under camp, take to boats: 108 hours rowing no sleep

- 15 April 1916: land Elephant Island

- 25 April 1916 – 10 May boat trip to S Georgia

- 30 Aug 1916 – remaining crew rescued from Elephant Island

- Mountain Literature Classics: The Wildest Dream by Peter and Leni Gillman 14 Aug

- Mountain Literature Classics: Harry Griffin, the alternative Wainwright 12 Jun

- Mountain Literature Classics: WH Auden's In Praise of Limestone 2 Dec, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog 15 Feb, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: South Col by Wilfrid Noyce 9 Jan, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: Free Solo with Alex Honnold 29 Nov, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: That Untravelled World by Eric Shipton 3 Aug, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight 4 May, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Menlove 9 Mar, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North 12 Jan, 2023

Comments

"I don't really go for the expedition accounts of today where they wave their emotions overhead like a flag ripped apart by the wind. I like my adventurers to show, but not to tell."

Hear! Hear! And wonderfully put.

It was, indeed, a remarkable journey by a remarkable group of men. And, for me, one of the saddest aspects is that, on their return to Great Britain many of the survivors joined up to fight in the war and subsequently were injured or killed in action, as if they hadn't endured enough already.

https://eshackleton.com/2016/09/06/the-fate-of-the-crew-2/