The sedimentary geology of the Pennines underpins one of Auden's greatest poems, says Ronald Turnbull.

Coming down off Ingleborough one day last summer, I stopped at the low pass above Sulber Gate and looked down on an extremely odd landscape. Because Yorkshire, as any Yorkshireman will tell you, is not like other places. The difference is in the Yorkshire landscape; it is in the Yorkshire temperament. But underneath all that, it's a different sort of rock.

Normal rock breaks down, over millions of years, into soil; soil grows plants, insects, and so-called intelligent life such as ourselves. Limestone starts off alive, and runs the clock in reverse, from biology backwards to geology.

In other places, hills rise out of the boggy lowlands, up to high cragged sides and sharp rocky summits. In Yorkshire the rivers run underground, while the hills rise in flat layers like a pile of pancakes. And the rock faces, instead of going up, go sideways. Take a traditional huge crag, cracked and waterworn; turn it over horizontal; plant ferns and little flowers in all the spaces – and you have the limestone pavement. And you're descending from Sulber into a bowl of wrinkled grey rock, like porridge left too long to go cold. A little path that vanishes as it wanders over the bare rock. And somewhere down over the edge of it all, a distant grey-green valley.

A fortnight later, a weird sense of déja view. The same wrinkly limestone landscape hemmed in by little hills. The same small yellow flowers; the same blue valley far below. But this time I wasn't in the Yorkshire Dales, somewhere on the way down off Ingleborough. This time, I was in Italy.

Rock creates the only human landscape" – Auden, letter to a friend 1948

But here, one of my favourite poets has been before me – both on foot and in the metrical feet of one of his longer poems; the 93 lines and 1100 words 'In Praise of Limestone', Auden's great poem about the North Pennines (plus a bit of Italy).

Critics agree that 'In Praise of Limestone' is one of the fundamental Auden poems, but disagree about almost everything else. Some don't even think it's about the North Pennines at all. Others see it in psychoanalytical terms, or an allegory of the human body. Here I'll take it as being, yes, about Auden's beloved home landscape the Northern Pennines – plus bits of Italy.

Because for Auden, the remote and run-down village of Rookhope, high in the Durham part of the Pennines and the bleak high-point of the Sustrans coast-to-coast bike ride, was a "the most wonderfully desolate of all the dales", a "sacred landscape", evoked in a late poem, 'Amor Loci' :

I could draw its map by heart,

showing its contours,

strata and vegetation,

name every height,

small burn and lonely sheiling

'In Praise of Limestone' is still in copyright, but it's online at the link here. My first chunk of commentary refers to the first 20-line segment, down to the line-break after 'pleasing or teasing'.

In Praise Of Limestone

The poem was written in Italy in 1948, then revised in the 1950s. It starts by evoking homesickness for the limestone landscape of the Yorkshire Dales:

With their surface fragrance of thyme and, beneath,

A secret system of caves and conduits; hear the springs

That spurt out everywhere with a chuckle,

Each filling a private pool for its fish and carving

Its own little ravine whose cliffs entertain

The butterfly and the lizard

But then it gets more puzzling. Is Auden really comparing the limestone landscape to a 'Mother'? A Mother with a son who's a 'flirtatious male': described in the 1948 version of the poem as 'the nude young male who lounges/ Against a rock displaying his dildo…'

And this cheeky boy is embellishing what now seems to be an Italian landscape: still a limestone one, but with temples and fountains and cultivated vineyards.

Cheeky nude boys with prominent dildos are not common in the North Pennines (despite that 'God's Own Country' film of 2017 by Francis Lee).

So we're not sure what Auden's getting at quite. But another quote from a letter suggests we may be on the right lines: "I hadn't realized how like Italy is to my 'Mutterland,' the Pennines".

So read on… The next line break, at line 59, comes after 'the various envies, all of them sad'.

Watch, then, the band of rivals as they climb up and down

Their steep stone gennels in twos and threes, at times

Arm in arm, but never, thank God, in step; … unable

To conceive a god whose temper-tantrums are moral

And not to be pacified by a clever line

Or a good lay

We're back in the North Country, with its 'gennels' (narrow cobbled streets), but now celebrating the effect of the limestone landscape on its people.

Auden is praising the limestone for its moral qualities. For being human in scale, "where everything can be touched or reached by walking". Its people are not mountaineers, not explorers, but hillwalkers.

accustomed to a stone that responds,

They have never had to veil their faces in awe

Of a crater whose blazing fury could not be fixed;

Life on the limestone is a "mad camp" – here we're in Italy again, rather than the North Pennines I think. But the ascetic saints have decamped to the granite. The fascists are drilling their armies on the alluvial plains. And the grim nihilists are away on the formless ocean.

The opening lines referred to 'we, the inconstant ones' – the ones so temperamentally matched to the limestone rocks: rock, which, crucially, dissolves in water and so is constantly changing and remaking itself.

But who is this 'we'? Himself and… who? The poets? The intellectuals of the 1940s? Or, I think, himself and us, the poem's readers.

But the final 30 lines shift the attention to one addressed as 'my dear'. The cheeky boy with the dildo? Some unspecified lover? Or – my own guess – the North Pennine landscape itself.

They were right, my dear, all those voices were right

And still are; this land is not the sweet home that it looks,

Nor its peace the historical calm of a site

Where something was settled once and for all: A back ward

And dilapidated province, connected

To the big busy world by a tunnel, with a certain

Seedy appeal, is that all it is now? Not quite:

The mad camp is not so trivial or cosy as it may appear. It's not really a 'sweet home'; it may seem 'backward and dilapidated'. But It has a function, a worldly duty:

[it] calls into question

All the Great Powers assume; it disturbs our rights. The poet,

Admired for his earnest habit of calling

The sun the sun, his mind Puzzle, is made uneasy

By these marble statues which so obviously doubt

His antimythological myth; and these gamins,

Pursuing the scientist down the tiled colonnade

With such lively offers, rebuke his concern for Nature's

Remotest aspects: I, too, am reproached, for what

And how much you know.

[Gamin: the male version of a 'gamine', a lively boy-girl such as the Audrey Hepburn character in 'Roman Holiday'. And yes, Auden was gay.]

To question the assumptions of the world leaders and their political facts and factions. To unsettle the modernist poet, so admired for his earnest habits, who has turned away from ancient myth. To chase the solemn scientist in its guise of cheeky urchin. To question Auden himself, uprooted, outside the sexual mainstream of his time, neither English nor American, in the process of converting to Anglican Christianity.

But always, the frivolities of Italy, the cheeky boy with his marble fountains, they have something important to tell us. That "the blessed will not care… having nothing to hide". And as for the North Pennines, in the lovely final lines:

when I try to imagine a faultless love

Or the life to come, what I hear is the murmur

Of underground streams, what I see is a limestone landscape.

Here's Auden reading 'In Praise of Limestone'. Or, if you prefer to have the words on screen as you listen, here he is reading the later version (without the dildo). Both are around 6 mins.

Ronald's love of hills and mountains, poetry, geology, the Lake District, 18th century literature and the Moor of Rannoch all emerges into the air like some digital version of the Great Douk in Yorkshire, via his weekly short effusions on the Substack platform aboutmountains.

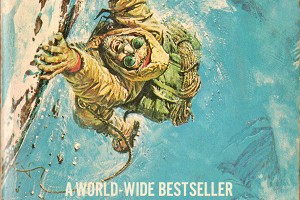

- Mountain Literature Classics: The Wildest Dream by Peter and Leni Gillman 14 Aug

- Mountain Literature Classics: Harry Griffin, the alternative Wainwright 12 Jun

- Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog 15 Feb, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: South Col by Wilfrid Noyce 9 Jan, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: Free Solo with Alex Honnold 29 Nov, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: That Untravelled World by Eric Shipton 3 Aug, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight 4 May, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Menlove 9 Mar, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North 12 Jan, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Conquistadors of the Useless by Lionel Terray 17 Nov, 2022

Comments

Thank you. I remember reading the poem years ago whilst living in Ireland. Back then we were discovering the primal landscape of The Burren which the poem seemed to entirely encapsulate.