Mick Ward writes about staying alive in an activity where risk is often part and parcel of the game...

These days, climbing is often lazily described as a sport and sponsored climbers glibly branded as athletes. While competition climbing certainly is a sport, there's a lot more to climbing than competitions alone. Many climbing disciplines involve significant risk. Getting it wrong may result in serious injury – or even death. So how do you avoid getting it wrong?

'He who survives is in the right...' (Nietzsche)

It's 1967. I'm 14. A shy, geeky kid, stunningly immature, even by the standards of those relatively innocent times. I've fallen in love with mountaineering. However my sole experience is a rushed solo ascent of Slieve Donard in the Mournes, risking expulsion by absconding from a school trip. Now, in the holidays, I conceive of a cunning plan.

At 8 a.m. I say goodbye to my mum outside our little caravan and head up the Bloody Bridge River valley. I've got a cheap rucksack, which is little more than a canvas bag. Some sandwiches, no water. A map, no compass. No hiking boots, just worn sneakers which barely last the day. Oh yes, I'm well equipped.

At least I have the vigour of youth which brings me, once again, to the top of Donard. Bliss! Down to the col and up Commedagh. In less than an hour, my score of peaks has doubled. Double bliss! What more might be possible? I follow the Mourne wall to Hares Gap and head up Slieve Bearnagh. The term 'summit fever' will not be coined for several decades – yet I've already succumbed to it. Bearnagh, Meelmore, Meelbeg. Five two thousanders in a row. How good can it get?

Summit fever... and where it gets you

Yet as I stand on the summit of Meelbeg, for the first time, uneasiness sets in. The day is well advanced. I know nothing about pacing myself and the vigour of youth is somewhat worn. Instinctively I know that I haven't got the energy to go back the way I've come. Rightly I don't try. Instead I plot a bold, direct route through the centre of the Mournes. It's probably the first big decision I've made in my life. Little do I know how momentous it will be.

Slogging up from Silent Valley to the col between Lamagan and Binnian, in my tiredness, I go far too high. The map gives no indication of a crag barring my way: the 500 foot Lamagan slabs. Somehow I cross their upper reaches. At one point, I'm clinging to a clump of heather which starts to give way. I dully think, "This is it." But the clump of heather doesn't quite give way. I survive, drag myself across the Annalong valley in a menacing, silent evening, keep doggedly navigating, finally regain my starting point at 10 p.m. I've been out for 14 hours, haven't seen a soul all day. My mum is frantic. Even as I try to allay her fears, I know, deep inside, that I should have perished on the Lamagan slabs. I also realise I've made fundamental errors. That day marked the beginning of my study of survival. Over half a century later, I'm still studying it, still hopefully learning.

So what did I get wrong? What did I get right?

So what did I get wrong? A long list! Feel free to improve on it. No journey plan left with others. No plan B in case of bad conditions. Biting off more than I could chew. On my own. No compass. No water. Little food. A crap rucksack. No proper footwear. No sunscreen, sun-hat or spare clothing. No plasters or first aid kit. No idea about pacing myself. No notion of how long things would likely take. (Interestingly I pretty much followed Naismith's Rule of an hour for each 1,000 foot of ascent and an hour for each three miles covered.)

Overall: lack of provisions, lack of equipment, lack of skills, lack of judgement. More than anything – lack of judgement. We've all got to start somewhere. But when you start, how do you know what you don't know? Back then, there were very few resources indeed.

What did I get right? Self-reliance, resilience, endurance, boldness when required (the innovative route back), navigational skills. Most of all, I fought for my life, I refused to give in. Ultimately, with survival, fighting for your life trumps all else.

Obviously nowadays few people venture into the hills as ill-equipped as I did then. But, whether walking in the hills, scrambling or visiting mountain crags, people still make fundamental mistakes. And, sadly, not all of them are as lucky as I was. Year in, year out, accident statistics tell their grim tales.

What was my biggest error? Lack of judgement.

What was my biggest error? Lack of judgement. It's said that experience is the name we give to our mistakes. If you survive your mistakes in climbing, you may develop judgement. The smart thing is to learn from other people's mistakes – mine, in this case. Of course other people's mistakes don't quite carry the same import but then neither do they come with the same cost.

When I started climbing, there was no book, no article, no person to tell me that I'd entered a war zone and that my judgement would come with a considerable price. In my first four years climbing, I met four people who died, five if we're being pedantic. The fourth death was particularly painful. After this, I could never be gung-ho again. Nor would I tolerate it in others.

Arf's Story

It's 1971. I go up to Lower Cove, in the Mournes, with Arthur Little. I'm nervous; the last time I was up here, Lucky Jim Patterson pulled a block off Dot's Delight and crushed his foot. Back then, pre-wires, pre-hexes, pre-cams, there was no protection. To my horror, the block hit the ground and bounced over the heads of Jim's mate and my girlfriend, Maggie. It could have – should have – killed them both. And, if Jim had come off, the force would have stripped the crap peg to which I was belayed. But Lucky Jim was well-named and he was a hard lad. He hopped up the remainder of the route with a crushed foot. I abbed off the crap peg and ran to give him assistance.

I tell Arf this but I can see he's not interested. He's got his sights set on Praxis, then the hardest route in the valley. We've got a few slings and garage nuts. We know there's supposed to be a peg runner, not in-situ, by the looks of it. I give Arf my peg hammer and my two pitons.

Arf moves confidently across the wall and bangs in a peg. It's his only protection. He continues the traverse, then suddenly, with no warning, he's in the air. Without gloves or a belay device (not invented, back then), I stop his fall and lower him to the ground. If that peg hadn't held, he'd have decked it. And I'd have been dragged over a lower outcrop.

I volunteer to go up Brewer's Gloom to get to the top of the crag and abseil for the peg. It's easy; I've soloed it before. I don't bother placing runners, run the three pitches into one. But on the top pitch, I feel really shaky. Why am I shaky? I don't know.

A little later, peg retrieved, we wander back across the crag, watch a team on another route. The leader falls off the top pitch and hits a broad, grassy belay ledge, from about 20 feet (no runners). Without a pause, he picks himself up, throws himself back at the rock and completes the route. Arf looks at me. "That was really impressive!" I say nothing. Personally I think it was bloody stupid. I'd have sat on the ledge, had a breather and sorted my head out before heading back up again.

That summer, Maggie and I go to the Llanberis Pass. Truth to tell, I'm glad to get away from Arf's intensity. We climb easy routes, meet lovely people, relax. Then we hitch to London to find work. Over the next few weeks, I think about Arf. His intensity worries me. Instinctively I decide that I don't want to climb with him anymore.

At Glendalough, on our way home, we bump into Lionel Carew. Lionel is the kindest man imaginable but the first words out of his mouth are thoughtlessly brutal. "Heard about Arthur Little? He got the chop in Glencoe." My body goes cold; I'm in turmoil. Maggie tries to comfort me but it's no good. Alan. Paul. Bruce. And now Arf. We walk past the layby where I first met Paul and Bruce. I can't make sense of any of it.

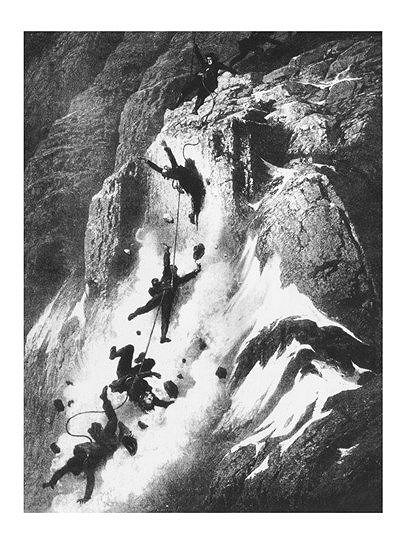

It appears that Arf and the leader of that other route on Cove were doing something on the Buachaille. They were found at the bottom, roped together, seemingly having fallen hundreds of feet. It was surmised that they'd been on easy ground near the top when the accident occurred. But who knows?

Back in Belfast, out of respect, I put on my only suit and turn off the Lisburn Road, into a maze of two-up, two-down terraced houses. This is hard-core Protestant territory. Surely every last one of them can tell I'm a Catholic? Madness to set foot here. But I'm beyond caring.

No surprise that Arf's house is freshly painted, the front step immaculately clean. I knock on the door; his dad lets me in. His younger brother's there too, dazed and silent with grief. His dad's a lovely man, a heartachingly lovely man. In the tiny, dark parlour, we talk for hours. I learn that Arf's mum had terminal cancer. He never told me. She died ten days after him. In less than two weeks, Arf's father and brother lost both of them.

I leave the house, walk back through those deadly streets, older, sadder, wiser...

'After such knowledge, what forgiveness? Think now.' (T.S. Eliot)

I've given you two stories; I could give you any amount more. It's almost fifty years since Arf died. Time for some tentative conclusions.

Is climbing a sport – or is it an adventure activity? Clearly competition climbing is a sport (sports are defined by their rules). But what about other disciplines, such as trad sea-cliff climbing? Surely that's more about adventure? But what's adventure? There are lots of definitions. Mine would be, 'Uncertainty of outcome where outcome matters', which also covers intellectual adventure (e.g. trying to find cures for COVID, Aids, cancer). If we look specifically at adventure in relation to climbing, it's rumoured that the late, sadly missed Phil Davidson, defined it thus: 'Adventure is when you could die.'

'Adventure is when you could die.' Ouch! We live in a consumer society where people are focused on winning, not losing. But, with climbing, you risk losing – maybe losing your life. People blithely argue that climbing isn't dangerous but I've known dozens of people who've been killed climbing. These days, even with pads and spotters, people get injured bouldering. Maybe being more aware of the possible dangers may make people more nimble at avoiding them.

'All the heroes are dead.' (Russian proverb)

Why did Arf and the other guy from Cove die? I don't know the specifics; nobody ever did. But, right from that day on Cove when they first met, I realised that both of them were too pushy. I'm told that the graveyard in Chamonix is filled with the bodies of young men from 18 to 26 – the classic age and gender of a combat soldier.

Are women as much at risk? Hard to tell. A couple of years ago, I came across a lady in her twenties, at Wallsend, in Portland. It was her first time climbing outside. She'd got most of the way up a 7a+ but unfortunately had succumbed to blind panic. So had her (male) belayer. Was she too pushy, trying a 7a+ for her first time on rock? Probably.

When you're in your teens, you tend to know few people who have died. Often it's hard to imagine that it might be you. When you're starting to climb, there's a lot that you don't know. And there's a lot more that you don't know you don't know. You don't imagine that you might pay the ultimate penalty for your ignorance. In a way, I was lucky. That day on the Lamagan slabs, when I was 14, taught me a priceless lesson.

Climbers' attitudes to risk have changed. I can remember going into Ilkley quarry in the early 1970s and seeing a guy soloing the first pitch of Curving Crack. There was a group of about a dozen people at the other side of the quarry, throwing stones at him, to see how close they could get without actually hitting him. Amazingly he was unscathed. They – and he – seemed to think it was hilarious. I was shocked. Imagine the outcry if this happened today! But maybe people were more accepting of risk back then, more attuned to it. Maybe not being attuned to risk paradoxically makes you more at risk?

Nowadays many climbers are accustomed to doing risk assessments in their professional lives. Do they do risk assessments when they go climbing? Unlikely. I've never done a risk assessment at all. But I'm constantly assessing risk – and not just in climbing. My ears are highly attuned to the sound of the grim reaper sharpening his scythe, coming for me.

'Beware of old men in a profession where men die young.' (Anon)

Assessing risk. On a serious trad route, it may come down to seconds, whether to commit or whether to back off. On a Himalayan peak, raked by avalanches, an even more fundamental question may be asked: should you be there at all? Whillans spent days on end at Base Camp on Annapurna, staring at the huge face above him for hour after hour, studying where the avalanches came down and where they didn't. He was determined to gain every advantage possible before he left the ground. Pre-route intelligence. It doesn't need to be as complex as Annapurna. For instance, is it wise to go on a west-facing sea-cliff in the morning when it's likely to be horribly soapy? Not really. But countless people have done so (including me).

Sunk cost. "I've driven all the way up from London and the Ben's in shit condition. What am I going to do?" Well you could drive all the way back home again. Or you could risk getting avalanched.

It's not rocket science; it really isn't. I can remember coming down from something in the Aiguilles and getting accosted by three British guys. "What are conditions like?" (It was a heatwave!) "Well I wouldn't be going on any ice routes..." "Oh? We want to do the Whymper couloir. We've only got a week's holiday". "Wouldn't touch that with a barge pole, mate." They remained unconvinced. With a morbid fear of dehydration, I headed off to the Bar Nash. Hadn't got my second pint down before someone came in. "Have you heard – a French guy's just been killed on the Whymper couloir?"

The sunk cost is sunk; it ain't coming back

I don't care if you've driven all the way to Scotland or you've only got a week's holiday in Cham or it's cost you a fortune and a huge amount of time and effort to get to your coveted Himalayan peak. The sunk cost is sunk; it ain't coming back. Maybe it was a bad bet. Well, shit happens. Better to write it off as a bad bet, rather than make it worse by risking your life on it.

Of course it's rarely just your life that you're risking. Most people have loved ones, families, friends. What about them? Look at what happened to poor Arf's family. Would you want that? Is the route worth it? Is any route worth it?

What about your climbing partner? In 'The White Cliff', Grant Farquhar made a masterly analysis of Paul Pritchard's near-death experience in Wen Zawn. Often, besides the victim, there's collateral damage – in this case, Paul's belayer. PTSD and survivor's guilt ('why them, not me?') can devastate lives.

Yet still ambition beckons. These days people want results and they want them fast. Ken Wilson used to say, "Serve your apprenticeship." He was absolutely right. The lady in Wallsend doing 7a+ on her first day out? Clearly she wanted results fast. But, if panic sets in, people get selective attention. They can't see viable alternatives – a key hold/runner/resting place – or, in her case, the simple expedient of just lowering off.

"The route will be there next year; the trick's to make sure you are."

"The route will be there next year; the trick's to make sure you are." Wise words from Don Whillans. Of course some routes do collapse: North Crag Eliminate, Deer Bield Buttress, Yankee Doodle, the Bonatti Pillar. But there are an awful lot more people who didn't survive because they let summit fever get the better of them, just as I did when I was 14. Mick Burke reckoned that 50:50 were OK odds – topping out or dying. I can't imagine Whillans – a man of legendary boldness – willingly choosing odds like these. And, with no disrespect to Mick Burke, don't you choose them either.

What if you're on a roll? If it's sport climbing, then go for it. If it's anything else, particularly mountaineering, be very careful indeed. Success breeds confidence – but you can be over-confident. Failure - if scrupulously analysed - can beget wisdom. Reinhold Messner noted that failure in the Himalaya forced him to analyse himself. In the mountains, particularly, over-confidence can get you killed. Arrogance can get you killed anywhere.

What about peer pressure? Potentially deadly. You can easily end up with a situation where everybody hides their misgivings and is afraid to speak up. If one person wants to bail, then, at the very least, that person should bail, unless bailing is more dangerous than carrying on. Bailing shouldn't be a democracy.

If you get a bad feeling in your gut – bail!

If you get a bad feeling in your gut – literally in the pit of your stomach – then you should bail if you reasonably can. It's your subconscious telling you to get out fast. Ignore it at your peril.

What if you can't bail? See it through. You'll probably be fighting for your life so you might as well give it everything you've got. Often you'll be amazed how much more you've got than you ever dreamed possible.

Judgement. It's all about judgement – when to be bold, when to bail, when to fight for your life. As Jim Bridwell said, "There's a fine line between badass and dumb." As with Whillans, so much wisdom in so few words. Heed them.

What happens when you're well and truly in the shit? In the celebrated words of René Desmaison, "A leader will emerge." Ironically it's rarely the gung-ho types; sometimes it's the least expected.

"Come back, come back friends, top out." (Roger Baxter-Jones)

Sometimes the fight is upwards, not for the ascent but simply because it's safer to carry on up: Hermann Buhl on the Eiger, giving it everything to save his life and eight others. Dave Yates on the Walker, a similar number of lives in the balance. Sometimes the fight is downwards: Tony Nicholls and his mates on the Troll Wall, Bonatti on the Central Pillar of Frêney where, one by one, his fellow climbers died in ascending order of age, until finally Pierre Mazeaud was the only other survivor. The legendary American failure on Latok I stands as one of the most astounding climbing feats ever. The team members were so highly attuned that the decision to turn back, agonisingly close to success, was implicit, unvoiced. Roger Baxter-Jones had three maxims of success in the great ranges: come back, come back friends, top out. The Latok team got the two most important maxims right, even under conditions of appalling hardship.

It really doesn't matter whether you're a boulderer, a sport climber, a trad climber, a big-waller, an ice-climber, an Alpinist, a Himalayan climber. What does matter is that you realise that you're on a continuum of risk. Ironically the more complacent you are, the greater the risk. The more pushy you are, the greater the risk. The less you listen to the 'still, small voice inside', the greater the risk.

Don't be a gambler

How do you manage risk? When I was very young, I read a comment by a cutting-edge Alpinist, Hilti von Allmen. He said that he'd never jump over a barbed wire fence for fear of ripping his jeans. I was astounded. How come this guy, who was pushing the limits, wouldn't take a chance on a barbed wire fence? It was many years before I realised. Von Allmen knew that he'd signed up to a highly risky endeavour. But he decided to be a risk-taker, not a gambler. So he wasn't going to take a chance he didn't need to take. And that included barbed wire fences. The best way to survive risky endeavours is to strip out every piece of unnecessary risk that you can. On a simple basis, that might include no soloing, always wearing a helmet, stick-clipping the first bolt (and the second?), padding out dodgy landings. Whether you do these things or not is up to you. Even if you get everything right, you can still be unlucky. Sadly Hilti von Allmen was unlucky; he died young. But he had the right attitude for survival.

And that's the rub. You can do everything right yet still be unlucky. You can have any amount of experience yet still be unlucky. But at least you're loading the odds in your favour. It's no coincidence that some of the world's greatest mountaineers have died in their beds, not on icy north walls.

Never get complacent!

The more aware you are of risk, the better able you will be to manage it. It's not rocket science, it really isn't. But never get complacent. A year ago, I went climbing at Toix. The routes could be done as single pitches, to lower-offs, or you could carry on up, as multi-pitches. I was climbing with someone with whom I'd never climbed before, so no way was I heading off on a multi-pitch with him. It was clearly established that I'd go to the anchors and lower-off. As I went to lower off the first route, I looked down - my last check. To my horror, I saw my companion had removed his belay device and was reaching for his climbing shoes. If I hadn't looked down – my last check – I'd have been killed. Single pitch, multi-pitch. What's in a couple of words? In this case, a life - mine. My companion had simply been complacent. I hadn't been complacent. And don't you be complacent either.

I'll leave you with perhaps the wisest words ever written about climbing. They were first published in 1871. 150 years later, they remain as relevant as the day they were written. Please read them, heed them and take them to heart. Their wisdom was earned dearly.

'Still, the last sad memory hovers round and sometimes drifts across like floating mist, cutting off sunshine and chilling the remembrance of happier times. There have been joys too great to be described in words and there have been griefs upon which I have not dared to dwell; and with these in mind I say: Climb if you will, but remember that courage and strength are nought without prudence and that a momentary negligence may destroy the happiness of a lifetime. Do nothing in haste; look well to each step; and, from the beginning, think what may be the end.' (Edward Whymper, 'Scrambles Amid the Alps')

With many thanks to John Amatt, Frank Corner, Tony Howard, Ken Lindsay, Paul Lindsay and Owain Llewelyn for their kindness in allowing me to use their photographs.

- FEATURE: The Corridor: A Review 14 Apr

- ARTICLE: Allan Austin Obituary – A Prophet of Purism 9 Jan

- IN FOCUS: Will Perrin - A Child of Light 14 May, 2024

- IN FOCUS: Custodians of the Stone 5 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: Clean Climbing: The Strength to Dream 31 Oct, 2022

- ARTICLE: Thou Shalt Not Wreck the Place: Climbing, Ecology and Renewal 27 Sep, 2022

- ARTICLE: John Appleby - A Tribute 28 Mar, 2022

- ARTICLE: We Can't Leave Them - Climbing and Humanity 9 Feb, 2022

- FEATURE: The Stone Children - Cutting Edge Climbing in the 1970s 14 Jan, 2021

- ARTICLE: The Vector Generation 21 May, 2020

Comments

Excellent article Mick, written from a perspective of long experience and thoughtful reflection. I can connect with so many parts of it, but can't help feeling that sometimes its just been the throw of the dice that has let me off the hook, even though I don't see myself as particularly bold or rash. It has a strong message for the newish climber venturing on to real rock - you need more than physical aptitude and self-confidence to acquire the judgement that will prolong your life. Thinking a lot about your adventures is mostly a good idea. As the old saying goes - the definition of experience is when you realise you are making the same mistake again.

Dave

Interesting article. But the example of complacency is surely just complete stupidity. If it's been established that someone is going to do a sport route and then lower off, why on earth would you take them off belay?

Another great article Mick.

When risk these days gets compartmentalized into risk assessments, you sometimes forget about the deeper and personal meanings it has, and what has shaped most people's climbing experience.

I remember you telling me about your first excursion as a young teenager, but didn't realise it was so formative, or daring!

Excellent article cheers

Thanks Mick, Best thing I've read on here in a long time, maybe ever. Topped off with a legendary Whymper quote.