Part 2: The Power of the Mind

Climbing coach and movement expert Udo Neumann is producing a UKC series on understanding and practising adaptable skills that you can apply to the dynamic and complex movements becoming popular in indoor bouldering, from IFSC World Cup finals to your local wall. Part 2/3 explains how the mind can be trained to improve your climbing movement...

Improvement in climbing starts with the mind. Every movement you perform shapes your brain, and to create long-lasting, positive change in brain structures there are three main training requirements: intensity, novelty and salience. In our practice, this means that low intensity, boring and "unimportant" exercise is NOT a good way to create positive brain changes.

The motivation to solve problems and accomplish a desired movement task facilitates learning.

Coordination

Coordination is the ability to get your muscles and your senses to work together to smoothly and efficiently accomplish a task. The right muscles need to contract at the right time with the right amount of force. Coordination can be improved with practice, but like strength it is very specific, so transferral to your climbing is not a given.

Research shows, however, that you benefit from practising. In this article, I want to give you some ideas of how to do that.

It takes time for your body to learn how to do something. Some muscles contract that should not contract, some don't contract at the right time and some contract with too much or not enough force. After some practice the muscles start to work together more efficiently. The timing gets better and the movements become smoother. Having good coordination is important because without it your strength, speed, balance, endurance and flexibility are wasted. You need coordination to succeed.

Gravitational Cognisance

As climbers, we can actually learn a lot from Wile E. Coyote. As for us, gravity is the coyote's greatest enemy. Unlike us though, gravity won't work on him until he looks down. He will not fall until he realises he should be falling. (Animation follows the laws of physics - unless it is funnier otherwise.)

During these funky modern bouldering moves, we also often do just fine, before we become aware of our vulnerability. It is then, when we start thinking, that we run into problems. If we just confidently followed through with what we were doing, the move would have been easy.

To stay in the cartoon logic, our moves then look like two actors in a horse costume, when the one in the front jumps an obstacle, whereas the one in the rear shys away from it.

Our brains predict the outcomes of our actions, shaping reality into what we expect. That's why we see what we believe, or, in this case, can't do what we are not confident in doing.

Movements possess spatio-temporal characteristics: they happen in space and evolve in time. Even minor errors during the time when muscles are activated and deactivated can cause major deteriorations in performance because the energy transfer is suboptimal.

Modern bouldering moves have all the spatial requirements plus much tighter temporal requirements than classic climbing moves.

Our sensory systems have to depict a rapid and continuous flow of incoming information to generate an accurate picture of what we're doing. And in modern bouldering time is not cheap; while it takes only a fraction of a second for signals to get from the hand to the brain, and fractions more to use this information to guide an ongoing action, these fractions can be the difference between falling and topping. The added demands on our timing alone makes many climbers struggle with modern bouldering.

What Wile E. Coyote and modern competitive boulderers also have in common is that the coyote is often more humiliated than harmed by his failures. Like competitors, the coyote could stop trying something senseless at any point – if he were not a fanatic.

"A fanatic is one who redoubles his effort when he has forgotten his aim."

– George Santayana

When climbing we are dealing with infinite positions and moves with sometimes contradicting demands. This provides huge amounts of complexity and novel movement information for the nervous system.

In fact, climbing demands such complex and integrated movements on the physical and psychological level that it isn't for a single day out climbing that every movement possibility could be trained into perfection. Instead, we can train our innate problem-solving ability.

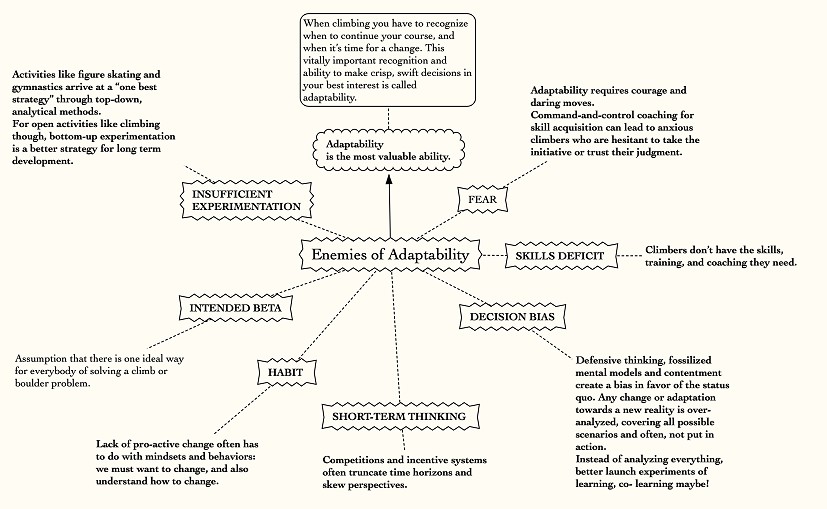

In the previous article I emphasised the importance of adaptability, your vitally important recognition and ability to make crisp, swift decisions in your best interest.

For learning something new, like modern bouldering, it is worthwhile to consider what might stand in our way of becoming truly adaptable climbers.

While many enemies of adaptability are beyond the scope of these articles, our mindsets decide our progress in any field.

Most people overestimate their adaptability

Research shows people view themselves as more flexible and versatile than they actually are. This is because we judge ourselves on how we intend to act as well as on how we do act. But unfortunately, our actions don't always match our intentions.

The four stages of competence

Also known as the four stages of learning, this is a model based on the premise that before a learning experience begins, we are unaware of what or how much we know, and as we learn, we move through four psychological states until we reach a stage of unconscious competence. Everybody is on different levels, even in skills that might seem to be related.

In unconscious incompetence, the learner isn't aware that a skill or knowledge gap exists. That would be Wile E. Coyote stepping over the edge, being in mid-air.

Wile E. Coyote, after looking down and realising he should be falling, would be considered a case of conscious incompetence. He becomes aware of a skill or knowledge gap. While he most likely doesn't understand the importance of acquiring the new skill, for us, in a similar situation, it's in this stage that learning can begin.

In conscious competence, we know how to use the skill or perform the task, but doing so requires practice, conscious thought and hard work.

For coaches, this stage is the most dangerous. As a coach I always have to remind myself: Yes, I know something, but I am far having a complete picture yet. This makes me vulnerable to the Dunning–Kruger effect. This is a cognitive bias in which people with low ability at a task overestimate their ability. It is related to the cognitive bias of illusory superiority and comes from the inability to recognise their lack of ability. Without the self-awareness of metacognition, we cannot objectively evaluate our competence or incompetence. Here is an overview of cognitive biases that we might harbor.

In unconscious competence, finally we have enough experience with the skill that we can perform it so easily that we do it unconsciously.

"I know this defies the law of gravity, but, you see, I never studied law."

— Bugs Bunny, High-Diving Hare

The model helps you to understand your emotional state when learning. If you don't know there's a problem, you are less likely to engage in the solution. On the other hand, if you are already in conscious competence, you might just need additional practice rather than training in this skill.

In the following sections, I'll show you 3 basic strategies of using practice and training to learn and move towards unconscious competence.

Beginner's Mind

"In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert's there are few."

Shoshin (初心) is a word from Zen Buddhism meaning "beginner's mind." It refers to having an attitude of openness, eagerness, and lack of preconceptions when dealing with an unfamiliar situation, even when being at an advanced level, just as a beginner would.

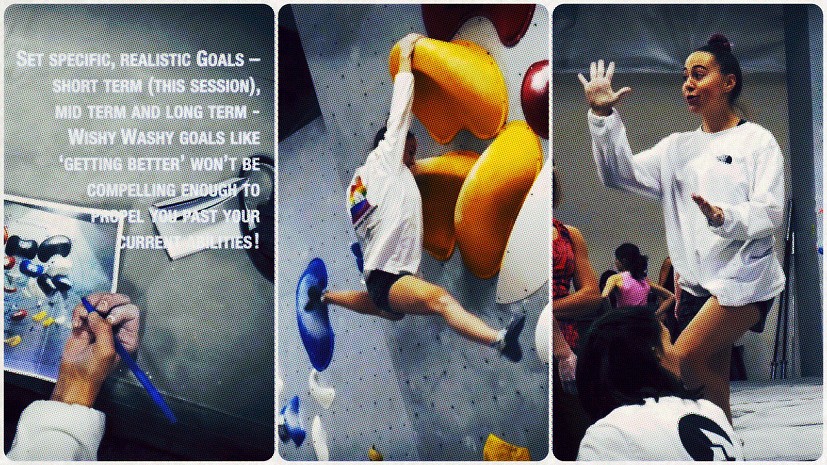

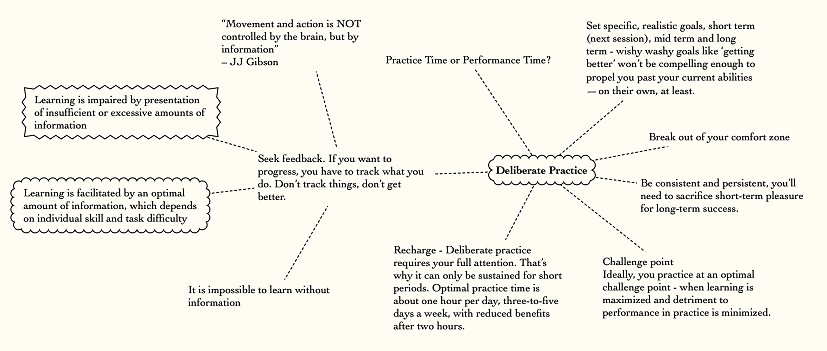

Deliberate Practice

This starts with an environment or task that has a clear intention.

Intention is an aim or plan, so when we set intent we give a clearly formulated plan to act.

Increasing intention directs attention; so clearly indicating the goals of the activity will direct attention to specific information, thus also specifying the feedback. Create an environment that maximises feedback to allow for implicit learning.

While regular practice might include mindless repetitions, deliberate practice requires focused attention and is conducted with the specific goal of improving performance.

As a beginner, just climbing is often enough for improving. But after a while we begin to carelessly overlook small errors and miss daily opportunities for improvement.

This is because the natural tendency of the human brain is to transform repeated behaviors into automatic habits.

Mindless activity, though, is the enemy of deliberate practice. The danger of practising the same thing again and again is that progress becomes assumed. Too often, we assume we are getting better simply because we are gaining experience. In reality, we are merely reinforcing our current habits — not improving them.

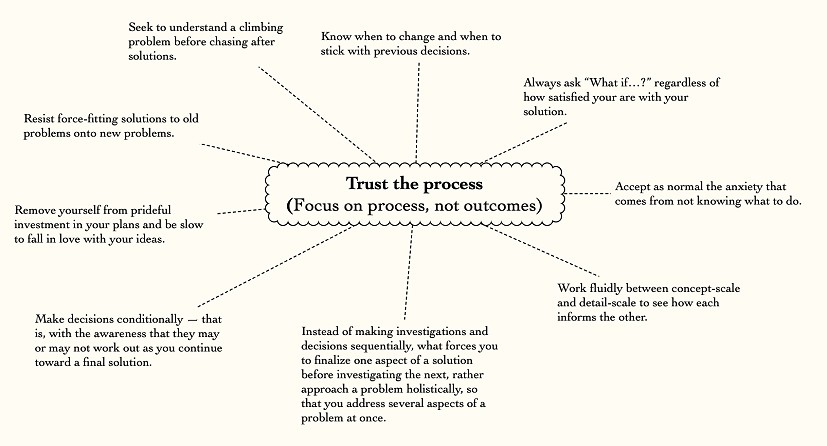

Focus on process, not outcomes

Skilled climbers are operating at the edge of their ability. They make mistakes, and explore options; trying, failing, trying again, failing again.

You can do the same while you are practising and be like children playing: intently focused, moving and perceiving, making decisions and problem-solving.

This way you are building on what is necessary for skill development in the context in which you are operating.

Your internal dialogue is "I wonder what will happen if…?" rather than "I must try and do it like this."

Spatial awareness

Good spatial awareness allows us to understand the environment and our relationship to it. Spatial perception also consists of understanding the relationship between two objects when there is a change in their position in space. It helps us think in two and three dimensions, which allows us to visualise objects from different angles and recognise them no matter the perspective that we see them from.

The following systems provide input regarding the body's equilibrium and about the characteristics of our surroundings:

Our Somatosensory / Proprioceptive System

This system is located around your body and provides information regarding the position of the many parts of your body, the movement of the limbs and the physical surface found in what is observed, like speed and stiffness.

This allows us to perceive our surroundings with shapes, sizes, distances, etc. Thanks to spatial perception, we can mentally reproduce objects in both 2D and 3D, and anticipate the changes in space.

The Vestibular System

This system detects the motion of the head in space and in turn, generates reflexes such as stabilising our vision and maintaining head and body posture.

The vestibular system provides us with our sense of movement and orientation in space.

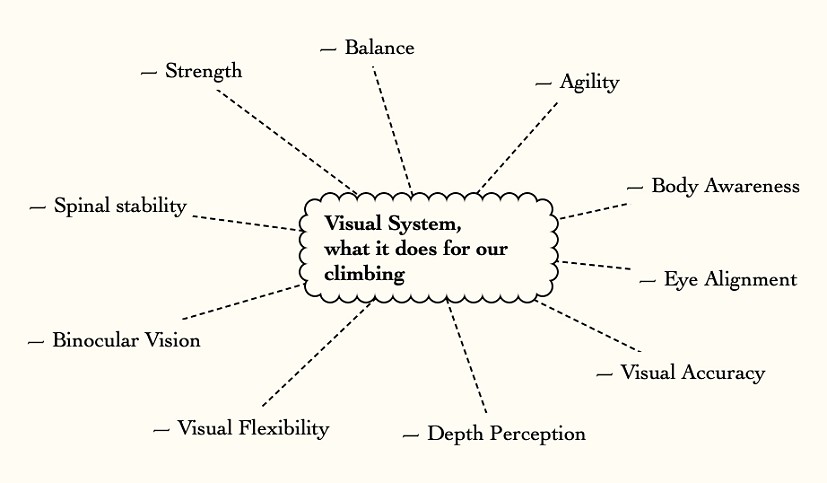

Visual System

The eye's visual receptors are located in the retina, in the back part of the eye. These receptors are responsible for sending the visual information that the eyes receive to the brain.

The Central Nervous System

The CNS receives feedback about the body's orientation from these three main sensory systems and integrates this sensory feedback and subsequently generates a corrective, stabilising torque by selectively activating muscles.

Gaze Behavior and Spatial Awareness

Our eyes are often called the 'windows to our soul'.

Vision is the most dominant of our five senses. It uses over a third of our brain, and is therefore an essential part of our interaction with the world.

Neuroscientists' research has discovered that the use of the gaze is very task-specific and that humans typically exhibit proactive control to guide their movement.

Usually, the eyes fixate on a target before the hands are used to engage in a movement, indicating that the eyes provide spatial information for the hands.

What we look at, when we look, how we look and how long we look for all have implications for how we process, interpret and interact with the environment around us.

The direction of your gaze even activates certain muscle groups or dampens others. In general 'eyes down' activates the flexors while 'eyes up' activates the extensors.

While this mostly works nicely for us, certain climbing situations require aiming and that head and eyes move as independently as possible from the rest of the body.

The link between attention and where we look is highlighted by how difficult it is to pay attention to one location whilst moving our eyes to a different location.

While climbing, you constantly aim for contact points with some body part or with your eyes.

In my workshops I have seen climbers closing their eyes while going for a hold. In most cases, that doesn't seem to be good strategy, since your body reflexively follows your eyes and stretches more than it would have otherwise.

"A man's reach should exceed his grasp, or what's a heaven for?"

– Robert Browning

Focus of Attention

An external focus (e.g. on a specific hold or point) enhances motor performance and learning relative to an internal focus (i.e. on body movements).

Benefits are seen in movement effectiveness such as accuracy, consistency and balance, as well as efficiency, including muscular activity and force production. Also, with an external focus, you are less likely to choke under pressure!

This is interesting for coaches intending to improve their athletes' performances. Instead of cueing a movement with an internal focus, e.g "contract this muscle", or "extend your hip", external cueing, e.g. "aim for the red hold" is more effective.

The upcoming book The Language of Coaching should be an interesting read in this regard.

Binocular Vision

This allows us to perceive depth and relationships between objects. Each eye sees slightly different spatial information and transmits these differences to the brain. The brain then uses the discrepancies between the two eyes to judge distance and depth. The result is the ability to see a 3-D image and distinguish the relationships between objects.

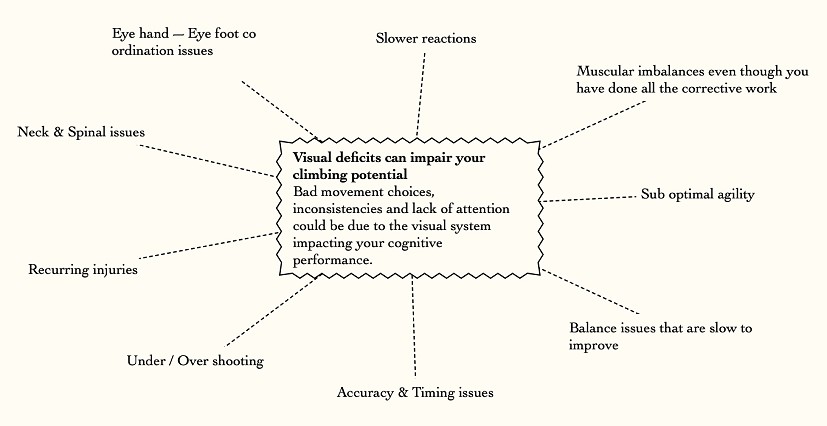

Eye-Hand and Foot Coordination

This is a complex cognitive ability, as it calls for us to unite our visual and motor skills, allowing for the hand to be guided by the visual stimulation our eyes receive and carry out a movement.

Climbing requires manual dexterity and visual perception to be able to judge the distance from one hold to the next and to coordinate the physical movements to reach the next hold.

Often when we miss a hold, our eyes failed to integrate the visual information into a coherent image.

Hand and eye always move cooperatively in our daily lives because both motor systems are tightly coupled with each other.

We use our eyes to direct attention to a stimulus and help the brain understand where the body is located in space (self-perception).

As you might have guessed, our reaction time for hands is faster than for feet.

Assuming a similar nerve conduction velocity, just the simple fact that our feet are further away from our brain than our hands are is the main reason.

Most people also show a greater preference for hand actuation and are more precise with their hands. A lack of hand-eye coordination, like our other cognitive skills, can be trained and improved.

All the more reason to try to improve our eye-foot coordination too!

The Quiet-Eye

The quiet eye is defined as the last fixed gaze on a target. The duration of this last gaze depends on skill and on the probability of hitting. Without controlling one's gaze, failed attempts become more common.

A long fixated gaze before initiating movement - the so-called quiet-eye - influences performance.

Performers tend to react to increased pressure by shortening their quiet eye period and moving their gaze around the target vicinity, rather than keeping it stable.

Research among athletes in which precise aiming is crucial, like basketball or darts players, showed that quiet eye training provides significant improvements in implicit learning.

The head and the eyes contribute at a constant ratio to get the gaze onto target.

This is why you should practise reaching with your eyes. Aim and reach with your gaze as you would with your hand or foot.

Making yourself want to reach a hold by aiming for it with your gaze and your brain, through the so-called ideomotor effect or materialisation of intention, will help you make your goal come true.

Visual Search Behavior

You might have noticed improved economy of visual search with fewer, shorter fixations and a decreased search rate on a climb that you have practised.

Even without a lot of practice, you can often improve your gaze and visual search behavior on short notice, simply by being aware of your gaze behavior.

When confronted with a move you cannot do, ask yourself: 'What do I look at, when do I look, how do I look and how long do I look for?"

Practising Eye-Hand/Foot coordination and aiming skills.

You will notice significant changes.

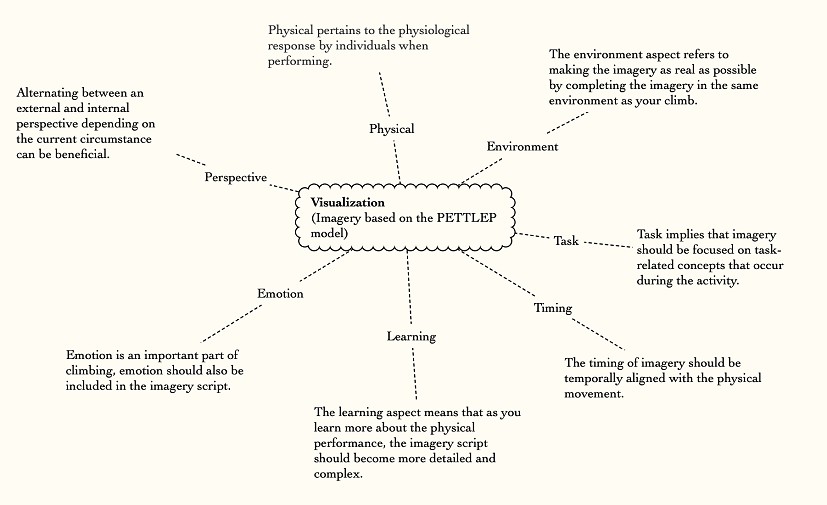

Mental rehearsal and visualisation

These are practical psychological tools to improve performance. Imagery or visualisation is the process that involves systematically rehearsing some behaviour by imagining a specific motor skill.

When you see an image in your mind, whether it is real or imagined, you have a greater chance of reciprocating that image.

Many climbers will run through different situations in their imagination as a kind of mental rehearsal. This way, when they are confronted with the situation in real life, their mind is already primed to respond to the situation in an effective way.

Visualisation is most effective when you focus on process rather than on outcomes.

The goal isn't to imagine yourself already standing on the podium holding your medal or clipping the anchors of Silence, but instead to imagine yourself doing the actions necessary to really get there.

Imagery is the use of the senses to create or recreate a physical experience in the mind. The connection between imagery use and performance success has been well documented in all activities.

Better climbers seem to make better use of the ideomotor effect or materialisation of intention.

Visualisation is a Skill

As a skill it can be practised and improved.

At first, your visuals might be a flickering, dim movie that flashes by rapidly. After practising, your mental imagery will get bigger, more clear and will include specific details, like colours, angles and sizes.

One thing you can try when practising visualisation is to turn up the lights in your visualisation. Make it brighter. In many cases, this alone leads to better performance on the next attempt!

Mapping Across the Senses

Using all the body's senses during imagery helps you in achieving vivid or "lifelike" images. Lifelike imagery helps the body to respond physiologically the same way it would if you were actually physically performing.

Inside and Outside Your Body

Mental imagery is most often associated with imagining oneself from either an internal or external perspective.

Internal imagery occurs when you use an image from the first person point of view (i.e. seeing the image "from behind their own eyes").

You might see some of your own body and the surrounding environment consistent with the normal visual field. Thus, the internal perspective can simulate a move before it is actually performed and helps you to feel confident about your ability to do the move.

An external perspective is a third-person view, where your entire body in the surrounding environment can be seen in action.

When using the external perspective, you see yourself similar to how you would look if you were watching yourself on television.

A benefit of the external perspective is that, with imagery practice, you can control the image to see yourself from multiple angles. This may be beneficial for making adjustments to your technique.

With increasing skill in the use of imagery, the image can be shifted fluidly from an internal perspective to an external perspective.

Then you are able to control and manipulate your images. This skill provides an opportunity to see positive processes and outcomes, regardless of the actual physical results.

If you fail at a boulder problem, you could then use imagery to see yourself correctly performing and completing the next attempt.

Control should also be used to temporally align the image with the actual physical performance, because imagery is more effective when this occurs. If it takes 20 seconds to physically perform your boulder problem, your imagery should also be 20 seconds in length. This prevents details from being omitted and adds to the authenticity of the image.

Consistency between the physical climb and the mental image of the climb helps in achieving peak performance.

After all these theoretical explanations, you'll be happy to hear that in the next article, we'll focus on actually doing it!

Until then, stay safe!

Udo Neumann is the author of Performance Rock Climbing, Der XI. Grad and Lizenz zum Klettern. Recent video publications include 'Climbing Technique of the 21st Century' and the 'Ideas to improve your Climbing' series. From 2009 -2017 he was the German Bouldering Team coach with World- and European Champions to his credit. Today, he advises federations and teams and coaches athletes and coaches. Check out his YouTube channel.