On International Women's Day, Anna Fleming speaks to French climbing icon Catherine Destivelle about her evolving career, subverting stereotypes and her respect for British climbing and its culture...

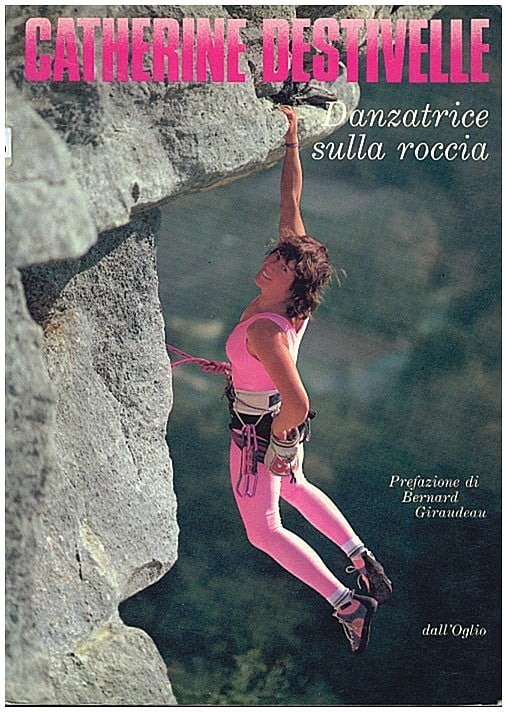

Since she began climbing in the 1970s, Catherine Destivelle has recorded a diverse and highly successful career, from hard sport climbs to world championship titles and alpine feats involving first ascents across the globe. In the '90s, Destivelle's achievements and her reputation for bold solos as a woman in a male-dominated scene attracted mainstream media interest and made her one of the most famous climbers in the world. Now aged 63 and based near Chamonix, Destivelle balances climbing for enjoyment with her mountain book publishing company, Éditions du Mont Blanc.

...they told me that I had killed mountaineering.

Interview edited for length and clarity

You started climbing in your teens in the Fontainebleau forest and have since travelled all over the world to achieve your goals. What is it that you love about climbing?

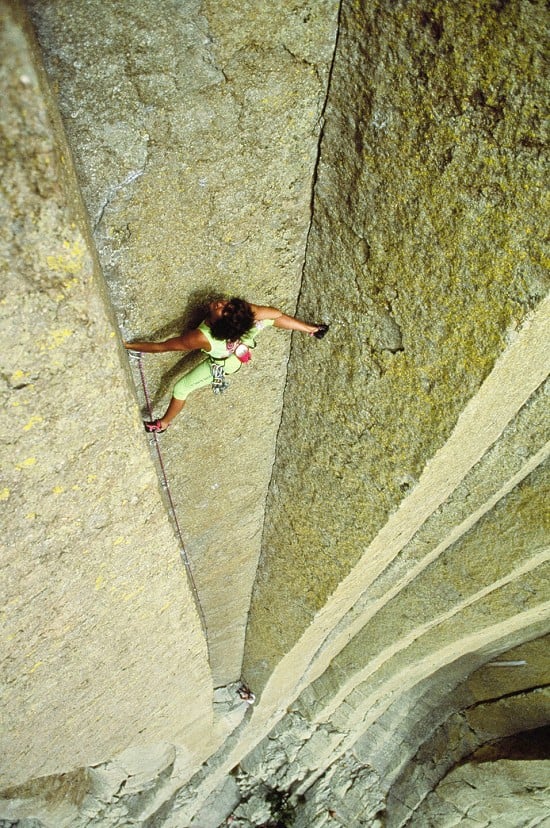

I love to play with rock. For me, climbing is a game. It's an activity where I don't think. I like playing with the structure of rock and ice. It's a way to escape from the real world.

You came of age as a climber in the 1980s when competition and sport climbing was first emerging. In this phase of your career, you climbed the first ever female 8a+ and won four world championships: Sportroccia (1985, 1986, 1988) and Snowbird (1989). What was it like to compete in these early events? Did you enjoy the competitions?

I didn't enjoy the competitions because they brought a lot of pressure. I started to be well known with photos in magazines and then at the competitions everybody was waiting for Destivelle to win or not. So it was a big pressure. Climbing under pressure is not fun for me because I was not used to this kind of thing.

Now young climbers like competing and they like having pressure; they climb better that way. For me, it was not like this because I didn't start climbing in that way. It was very different to what I knew. When I started climbing in the competitions I was old—I was 25 already.

Before, I had done a lot of climbs alone or just with friends and so to suddenly to appear in the middle of thousands of people, that felt very different. But I had to go to the competitions as I had started to become a professional climber and it was only fair that I took part.

At many of these events you were competing against Lynn Hill, the American world champion (UKC Interview). As the two stand-out female climbers of your time, there was a lot of media attention on the two of you. What was it like to share a podium with Lynn?

I have good memories of it because she was very strong and she liked competing very much. But she was not aggressive. 'Good luck!', we said to each other each time, 'good luck!' And so it was nice, compared to with others [competitors]. There was a lot of attention and expectation. People were waiting for us.

While you were rivals, did you also become friends?

I was busy at this time. Each time we met was at these types of events. We never climbed together on a cliff because I think we climb in different ways. I like to go climbing early in the morning. And most climbers prefer climbing late in the afternoon until… I don't know? But I prefer climbing in the morning and then reading, planning or doing something else in the afternoon. I couldn't stay a full day at a cliff. It's too much for me. I like climbing, but not a whole day.

What time do you start, as a morning person?

It depends on the season. In June, July, August, maybe sometimes at five or six in the morning. But I was in bed early! So I was not in the same rhythm as Lynn. Maybe that's why we never met really.

In becoming a professional climber, you were in the news and starred in many films. How did you find the balance between climbing and media attention? How did you handle the spotlight?

The balance was OK because doing a film doesn't take much. They are a kind of window. They're a way to meet other people and I like to think that maybe they will inspire people. I have good memories of the films. I felt I could share something rather than climbing only for myself. I could show how climbing can change your life. Climbing is a good way to travel. You meet people in different ways to the general public. If you go to Africa for climbing, the exchange with the people is not the same as it will be for most tourists. It is interesting. More interesting.

Lots of your films have become classics with millions of views, from soloing the Old Man of Hoy to climbing in Mali. What was it like to make those films? Do you still have connections with the people in those places?

Yes I still have some connections with people in Mali. I received some letters, but I have not been back since. It's difficult now because of the context. It's dangerous to go to these places. At that time they were very happy because they said that this film had done a lot of good publicity for them. And also, we changed the rules on hospitality there. When a family hosted us in their home, we wanted to pay them and this was new for them. It was the same with food and cooking. There are no restaurants in these villages, so we said we would pay for their cooking. We explained our itinerary, saying we would like to go to these places and we will pay for this. For these people it was completely new. They had never been paid for hosting before. So we introduced a new way to make their living.

Some people were upset about this because before, the villagers were inviting us in for free. But they have nothing. So we thought it was not fair to operate this way. It seemed fair to pay something to stay in their place. It's the same in France, anywhere. You can't go in their house without paying.

After an incredibly successful run at competition climbing you retired in 1990 and transitioned to alpinism. What was behind this decision?

I did the competitions because I thought I had to because I was a professional climber. But then I had enough and wanted to climb in the mountains. Before the competitions I was mainly a mountain climber, rather than a rock climber. When I was young I climbed on ropes in order to climb better in mountains. Fontainebleau was a training ground for the mountains.

During the competitions you can't do both. You can't go climbing in the mountains and do the competitions. They are two different things. I decided to quit so I could focus on mountains. I had these dreams, since I was a teenager, and I couldn't realise them if I had to keep doing the competitions.

This was a way to say that this is a first. Not the first woman. The first solo on-sight.

What were your teenage dreams?

I wanted to climb the Eiger north face and to free climb some routes on the Grand Capucin, the Dru or in Yosemite. I had many dreams but they were not very precise. But I was ambitious when I was young!

Alpinism requires a radically different set of skills. In your memoir, Rock Queen, you write:

'As far as I was concerned, to be a good mountaineer, meant being able to develop in mixed terrain, where a knowledge of ice climbing was also needed. I had always been in awe of ice and snow, which I did not know well and whose climbing techniques I had never mastered, since I had always carefully avoided them. In order to become a real mountaineer and go forward in my profession, I would need to learn to climb on ice.'

What was it like transitioning to alpinism? Did you find it difficult, or did it feel natural? I gather you had already climbed the Dru as a teenager.

I was fit so I just went out climbing. Jeff Lowe was a good teacher and we climbed together. Whereas rock climbing is more technical and your body has to move differently, climbing on ice is quite simple. The movements are all almost the same. The problem is the structure. I did not know the structure of ice or snow very well.

Ice climbing mainly requires the knowledge of the structure of the ice and confidence in the structure and in your tools. It's an affair of the mind because these formations can be quite dangerous. Sometimes you have to play delicately with the ice.

In this way it is very different to rock climbing. You have to get used to the ice. It demands experience. For me, ice climbing is more about experience than technique, since I was already a climber.

You were the first woman to climb the Bonatti Pillar in 1990. In 1991 you opened a new route on the Petit Dru (Voie Destivelle). From 1992-1994 you soloed three of the great north faces in the Alps in winter. You also climbed in the Karakorum and established new routes in Antarctica. What do you gain from undertaking such demanding routes in vast, remote mountains?

Confidence in myself. A way to prove to myself that I'm able to do this thing. It's ambitious. Climbers have a big ego, no? I find happiness, but then the question is, what next?

Is there one style of climbing that you prefer above all others?

I like all of them. I am better at some of them than others, so I prefer the styles in which I'm better, but it's still a game each time. Now I live near Chamonix and the south of France, so I mainly climb on cliffs with ropes. I like to go back to Fontainebleau, but the forest has changed a lot since I was young. There's lot of people now, thousands of climbers arriving every day, all week. It's very different from when I started climbing there. Then nobody was there during the week and since you don't need a rope, I used to go climbing with friends or alone. It was easy.

Which achievement has meant the most to you?

Probably the Eiger, because I was not an ice or mixed climber and so it meant I had to master the ice. I was a beginner at that time and was scared of the ice and snow. In the end, as it turned out, the ice was the easiest thing on the Eiger, but I didn't know this would be the case. I was a beginner at that time. Rock climbing was a lot easier for me.

Following your winter solo ascent of the Eiger north face in 1992, you wrote:

'I was very pleased with the recognition, which seemed to mean that maybe in their eyes I was no longer just the girl climber who was always in the news. I had become a true alpinist.'

How did you feel after climbing the Eiger?

After this climb, the newspapers said that this was the first female ascent. But for me it was a first ascent because I was the only one to solo this face on-sight – without knowing the route before. It makes a big difference when you don't know where you are going. The climbers before had known the route because they had climbed it before. That was something I didn't do. Just on-sight. It was the same for the Grandes Jorasses and the Matterhorn. I didn't climb either route before.

This was a way to say that this is a first. Not the first woman. The first solo on-sight.

Your big solo climbing projects on the Matterhorn, Eiger and Grandes Jorasses, took a long time to plan and put into action:

'It took me three years to climb those three mountains. I both like and need to take my time to digest each ascent. One major project from time to time is enough to satisfy me completely.'

How did you arrive at these projects? How did you find them as an idea in your head and what does a year of preparation look like?

I thought one year was enough. I had other things to do – I went on expeditions and did other things, which meant I wasn't focused only on these climbs in the Alps. It's important to mature a project and to think about it. There's not much preparation, it's mainly thinking about it so that by the end you have thought about it so much you have the impression that you have done it already. Then when you go, it seems natural. There's no fear. Then you want to go because you know it's something you really want to do and you're happy to be there, and that's all. Then it feels natural. I have to let things mature in my head to be ready.

Through this I feel comfortable with the fact that I'll be alone with no security. When I have these projects I must be fit and relaxed in my head. Since these routes have been around for a long time, they're never technically very difficult. You just have to climb naturally.

Back to the Eiger – after this you said people no longer saw you as the 'girl climber' who was always in the news. Was the Eiger a turning point for you?

Yes. Some climbers were jealous of my situation. They said that I was taking a place that they could get and I can understand. For the same level of climbing, I would get more publicity because I'm a woman. So they said that it was easier for me because I was a woman. So I had to take care of that. I wanted to make sure that what I was going to do would be something – not a woman's ascent – but a first. That's why I decided to climb the Eiger on-sight. So nobody would talk badly about that. But in fact, nobody knew that I had done it on-sight. It's very strange. It was exactly the same for the Grandes Jorasses.

Climbing has been a male-dominated world. There were stereotypes that women couldn't do elite alpinism and sport climbing. As public figures, you and Lynn Hill did much to challenge these stereotypes. What did it mean to be a 'girl climber' in the 1980s and 1990s?

For me, it was no problem. My friends were very nice and we didn't talk about women or men, it was not a subject. I never saw issues and never had anything to deal with. I just had a problem with sponsors and the fact that I got more publicity. This was the only thing. But the Eiger closed their mouths. They were nice after that—although they told me that I had killed mountaineering.

You 'killed mountaineering'? How?

I don't know why they thought that. But they said that after what I had done, no man could do anything. So you killed mountaineering. It's stupid but…? I think they meant that no one would speak about them after what I had done.

Have you noticed any changes in attitudes towards women climbers since the 1980s and '90s?

Right now there are more women climbing everywhere. Things are changing a lot, but some women still think that they don't exist in the eyes of the guys. They think that guys are still saying OK, let me go ahead, because you will not be able to do that as well as I can. But for myself I never had that problem. I hear some conversations like this and a lot of women feel the need to climb together, in women's teams and things like that. Since I never had this problem, it's difficult for me to think in their place.

What do you think of the recent rise of all-women climbing groups and events?

Why not?! It's nice. It seems to be a very happy situation, so very good! Some women are shy or they might prefer climbing with other girls. Some women can express themselves better in these groups.

In 1997, you soloed the Old Man Of Hoy while four months pregnant. After having your son, did your climbing motivations change?

Not really—but I was a mother hen. I had a normal life. A woman, a mother-life, I would say. It was my choice. I didn't stop climbing: I climbed in the morning or the afternoons when Victor was at school. I climbed because I liked it, but not much in the way of climbing projects. I did some little expeditions but very short—one or two weeks. Otherwise everyday I was there at the school gates.

I didn't miss climbing when I shifted to mothering because I had climbed a lot before. And I can't climb all my life everyday. So if I can't climb, it's no big deal. I can do something else.

I have done other things since. I've done films, wrote a book and now I'm a book publisher. I like climbing, but it's no longer my main goal.

'Besides, my whole life is not just about climbing mountains – I do not want to climb all the time, or to collect routes – that would make me think I was going nowhere. I need to occupy my mind with more than just climbing moves and have other activities.' - Rock Queen

Within your very successful climbing career, you also took time to do other things. This seems an unusual approach, as climbing, like all sports, can be all-consuming. What else do you like doing? How do you make the balance?

Right now I'm a book publisher so my ideas are focused on this. I can't do things half-way. I have worked hard for this company [Éditions du Mont Blanc] and I find it very interesting, and that's why I do it. In 10 years I have published 120 books. So now it's a real company. We published a range of big books, small books and books for kids. I have five collections, so it has been a big investment of my time.

How do you approach those book projects? Is it similar to a climbing project?

Yes, kind of. I try to publish books that nobody has done before. I publish books on subjects I would like to discover or books on subjects that will be interesting for the general public. When I have ideas I call writers and ask if they could write about this or that. I have translated books from English, Spanish and German to French because I think they will be interesting for the French public.

Before you couldn't find any kids' books about alpinism. I have published children's books that explain alpinism, climbing, caving or trekking—these kind of things—how they started and giving a story. We also publish fiction. I have some mountain thrillers—but no romance!

You've written a memoir yourself—Rock Queen—would you write another book?

I wrote Rock Queen in 1996. A long time ago! I would not write it now in the same way. Maybe I would write another one—not now, but maybe. It would be another memoir, but very different from Rock Queen. That book is mainly action and not thinking much. A new book would be more personal.

I like the sea cliffs because we don't have such climbs in France. And I like the gritstone—the rock is very nice. Cornwall, Gogarth, Scottish sea stacks.

I have heard that you are working on a documentary on the history of UK trad climbing for European Arte TV. Can you tell us more about this film?

We have done a film to explain that mountaineering was invented by the British. The film explores where mountaineering came from. It was very interesting to research. We filmed all over the UK, in Dorset, the Lake District, Snowdonia and on Ben Nevis and met some people who spoke about the spirit of British alpinism, and the culture over the last 200 years.

Mountaineering was founded by very wealthy people who made rules which we still follow. 'By fair means' is very important in mountaineering. So it's full of stuff like that.

The British were the first to use the word mountaineering. It was a Romantic writer who introduced this word: Wordsworth in the Lake District. It's very interesting. The Alpine Club was the first alpine club in the world and they climbed most of the 4,000 metre peaks in the Alps. So they were the first! And they were the first to climb Mont Blanc without any guides in the 1830s.

Did you find out why we were the first mountaineers?

Because you are an island! You need some adventure...

It's funny, the British, you have the Munros, the Marilyns and stuff like that. It's unique! It's fun. It's a way to have some adventure. We don't have anything like that in Europe, in France or Germany. We don't need to have these ideas. It's funny! I would like that too. It's good motivation.

Tell us more about your climbing experience in the UK. A lot of Europeans would not come here as a climbing destination because they say the weather is too bad and our mountains are too small. But you've been climbing in Orkney, on the sea cliffs and winter routes on Ben Nevis. What do you like about climbing in the UK?

It's adventure. I like the spirit. I like the way you do it. I like that I don't find much equipment on the faces. So it's an adventure each time. I like being in the UK so I said to my partner, we could spend some holidays in the UK? He loves it now. Before he did not, because he did not know [how good it is]. It's unique.

I like the sea cliffs because we don't have such climbs in France. And I like the gritstone—the rock is very nice. Cornwall, Gogarth, Scottish sea stacks. It's nice and a good adventure.

What advice would you give to climbers starting out now and getting into climbing?

Work on your feet. Technique on your feet is very important to save strength. It's very important to feel the sole of your shoes on the rock and make sure you have confidence in that. Then go out with some good friends who can share their experience in a safe way. It's not good to be scared. Safety has to be a big point in the UK especially. In the climbing walls it's not a big deal, but outside in the UK you have to be careful. There is no protection like the French bolting, in the UK you have to place your own protection so you have to make sure that they are solid.

In 2020 you became the first-ever female recipient of the Piolet d'Or Lifetime Achievement Award. What does this award mean to you?

I was proud that they gave it to me. Compared to other alpinists, maybe it's not fair that I have it. But anyway I feel honoured and proud. I hope this prize will inspire other women.

Are you still climbing? If so what are your motivations?

Yes. My motivation is just the same. I like playing with the rock and feeling good. I forget the books when I climb, it's good for my head. It's a holiday. When I go climbing, it's just relaxing.

Any more projects lined up? Climbing, book or film projects?

I have a lot! Too much. I can't stop but I don't know which one I will do. I can't sit without doing anything. This is my problem. I have a lot of ideas but what will appear? I don't know.

- ARTICLE: Top 10 Borrowdale Routes at VS and Under 22 Jan

- ARTICLE: Herstory 7: The Rise of Women Mountain Professionals 27 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Herstory 6: Lhakpa Sherpa's Long Dream of Everest 31 May, 2023

- HERSTORY: The Climbing Cholitas: Skirts to the Top for Women's Empowerment 2 May, 2023

- HERSTORY: Alison Hargreaves: Climbing Her Mountain 7 Mar, 2023

- HERSTORY: Wanda Rutkiewicz and the battle for women's climbing 13 Feb, 2023

- HERSTORY: Lady Climbers of the Long Nineteenth Century (1850-1914) 20 Dec, 2022

- HERSTORY: ORIGINS: The surprising origins of women's mountaineering - 1770-1830 9 Nov, 2022

- ARTICLE: The Cobbler: A Return to Mountain Cragging 7 Sep, 2021

- ARTICLE: A Climber in Lockdown 14 May, 2020

Comments

Legend...my fav climber of all time.

That’s great. What a star ⭐️

It's easy to forget how damn good she is at climbing

Great article, Anne, thanks so much for taking the time to speak with her and documenting it. A remarkable human being and climber.

Really nice read, great to see such a legend still getting media attention.