Anna Fleming profiles four women from the archives of climbing history, and gives us a glimpse into the origins of women in mountaineering.

'Once at the summit, I could see nothing clearly, I could not breathe, I could not speak'

Marie Paradis

On 14th July 1808, a woman stood on top of Mont Blanc. Marie Paradis (30) was an ordinary woman who had done an extraordinary climb. A peasant from Chamonix, she worked as a maidservant and also ran a small tea shop. Local guide Jacques Balmat, who had done the first ascent of Mont Blanc in August 1786, took her up the mountain, together with his sons who were friends with Paradis. They encouraged her to join them since she was strong, a good walker, and a 'stout hearted wench'. The fame would help her, they urged, after the record-breaking ascent crowds of visitors would want to meet her and this would be good for business. Their proposition was correct. Paradis became the first woman climber celebrity.

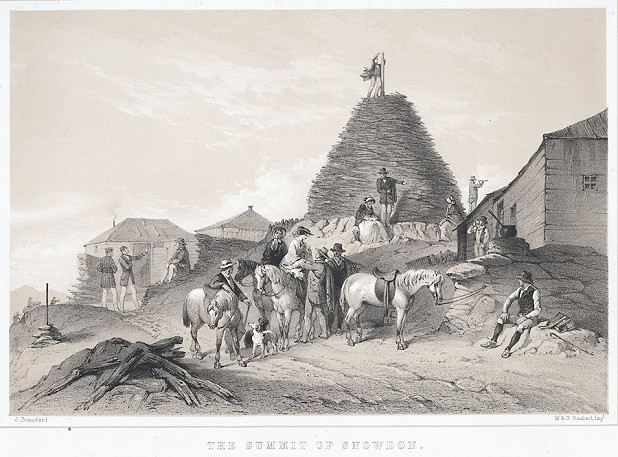

Her climb took place at the dawn of Western mountaineering. People began mountain climbing in earnest from the 1770s. Interest in botany, geology, and natural history spurred the activity along with a growing cultural fascination with the Alps. Travel guidebooks became popular, helping early tourists navigate unfamiliar terrain both in the Alps and at home. Snowdon was first 'officially' climbed in 1639, and Ben Nevis in 1771. The early mountaineers walked, scrambled, and tackled snow slopes in their quests up the mountain; rock climbing, in the form that we know, didn't emerge until later in the nineteenth century.

Looking back on those first mountain days, one assumes that the wild uplands were a male territory. The history books are full of men's ascents, and literature shows the same bias. The Romantic poetry of Shelley, Byron, Keats, Wordsworth and Coleridge did much to popularise mountain climbing, but they seldom mention the presence of the fairer sex. This absence leaves one wondering, were women there at all? When did ladies start going into the mountains? While history has favoured the male story, with a little digging, it turns out that women were up there, high on the mountains, right from the start.

'And now you must mount your old friend Pegasus, and go with me to the top of Snowdon to adore the rising sun'

Elizabeth Smith, 1798

In July 1798, a 22-year old woman went up Snowdon with her mother, aunt, and a local Welsh-speaking guide. The women began walking at 11pm aiming for sunrise on the summit. To a modern reader, this approach seems surprisingly intrepid. But in fact, night ascents of Snowdon were not unusual. A manuscript from 1775 held in the National Library of Wales reveals an anonymous woman voicing her frustration that her group (a party that included three women) would not set out to climb Snowdon at midnight, as she desired, but at 8am the next morning.

When Elizabeth Smith began her climb in the darkness, rain threatened and a violent wind began. As the ground steepened, Smith's aunt became frightened and could go no further. Rather than abandon the climb altogether, Smith's mother accompanied the aunt back down the mountain, allowing Elizabeth to continue with the guide. She happily traversed the precipices and reached the summit at 4.15am, writing of her ecstasy and delight. 'I was enjoying the finest blue sky, and the purest air I ever breathed.' At the close of day, Smith proudly recorded her athletic achievement of having completed 'almost thirty-nine hours of almost constant exercise.'

We know all these details because Smith wrote a brilliant account of her climb in a letter to a female friend in Bath. Smith's writing is witty, funny and insightful. Despite never going to school, she was an intellectual, polymath and linguist. She studied German, Arabic, Persian, Latin and Hebrew, translating the Book of Job from Hebrew and the Memoirs of Frederick and Margaret Klopstock from German.

Smith's mountain-climbing temerity was not limited to her Snowdon ascent. A few years later, she climbed Helvellyn with her sisters on a rare 'manless' and 'guideless' expedition, as their friend Thomas Wilkinson explained:

Smith clearly had a passion for mountain adventures, and men like Wilkinson did not seem especially concerned about her exploits. However, on an excursion into the Langdale Pikes, she unsettled her group by disappearing up a cliff:

This astonishing act took place around 1801. It is one of the first accounts of a woman rock climbing. Bear in mind that the first recorded rock climbs happened when William Bingley and Peter Williams climbed Clogwyn Du'r Arddu in 1798, and Coleridge descended Broad Stand in 1802. Elizabeth Smith – a woman – was thus rock climbing at the same time as the first pioneers.

Unfortunately, Smith's intellectual and mountaineering exploits were cut-short when she died in 1806 of consumption, aged twenty-nine. Had she lived longer, who knows what she would have accomplished.

'That is the lady I saw ascending Snowdon, alone!'

Ellen Weeton, Journal of a Governess

Ellen Weeton, a governess in Ambleside, also wrote compelling accounts of her mountain climbing in her journal. Journaling was extremely popular then; unlike modern diaries, journals were written to be read by friends and family. Weeton's writing is so good it was eventually collected and published in 1969 - over a century after she died.

Her journal paints a brilliant picture of the emerging Lake District mountain culture. She describes a group jolly up Fairfield, in which a mixed group of twenty men and women yomp up the fell and enjoy a lavish picnic on the summit. Their repast included veal, ham, chicken, gooseberry pies, bread, cheese, butter, a hung leg of mutton, wine, porter, rum, brandy and bitters. Compare this to the bread and milk that Smith took up Snowdon and you glimpse the range of mountain diets at the time!

While Weeton participated in group trips, she was more remarkable for her solo feats. In 1812 she went on a solo walking tour of the Isle of Man, where she surprised the locals with her 'decent' dress:

Weeton's most significant mountaineering achievement came in 1825 when she summited Snowdon alone. For to climb as a woman, without guide or companions, was unheard of. She dreamed up this 'wild scheme' in 1809: her mountain project had been sixteen years in the making.

On Snowdon, Weeton deliberately dressed in the 'plainest garments' to avoid notice. Halfway up, she met a man and an incredulous guide who could not understand why she was there alone. Had she lost her guide? The men tried to take her into their care. But Weeton was determined. She feigned deaf and 'walked as fast as I could' to escape the unwanted assistance:

In contrast to her independent mountain successes, Weeton's life on the ground was troubled. She entered a disastrous marriage in 1814. Her husband was extremely violent, beating her 'almost to death'. In 1821, he appeared in court for assault on Weeton and they separated, which was extremely rare in those days (the Divorce Act did not come until 1857). Weeton had to give up custody of her daughter who she didn't see for seven years.

Like Smith, Weeton did not court publicity. She was quietly ambitious, seeking personal pleasure and fulfilment in the mountains. Above all, the mountains gave her space to think:

'our ambition now mounted higher'

Dorothy Wordsworth, Guide to the Lakes, 1822

Sister of world-famous poet, William Wordsworth, Dorothy Wordsworth was no stranger to the emerging cult of mountain-worship, but it took some time for this woman to get into the heights herself. Unlike Smith and Weeton, Dorothy's mountain journey followed a gradual trajectory of slowly increasing confidence.

Dorothy had a traumatic childhood that left a lasting legacy of depression and anxiety. Her parents' died and she was separated from her brothers. When she and William were eventually reunited, the siblings became inseparable. She never married. Dorothy was the poet's companion – his 'eyes and ears' – recording everything in her journal for him to write into a poem afterwards. Her observations were razor-sharp and many of Wordsworth's best-loved poems were composed in collaboration with Dorothy. Without her there would be no daffodil poem, for the daffodils danced in Dorothy's journal first.

The siblings lived in the Lake District and Dorothy accompanied her brother everywhere – but not up the mountains. When William and close friend Coleridge went high, Dorothy walked so far with them before turning back, much like Smith's aunt on Snowdon. But in time this changed.

In 1818, aged forty-six, Dorothy set out from Borrowdale with her friend Mary Barker and a guide. Together the three climbed to the summit of Scafell Pike, the highest point in England. Bursting with pride, Dorothy wrote of this 'feat' in heroic terms, celebrating their 'uncommon performance' of reaching the 'point of highest honour'.

Dorothy described her ascent of Scafell in a lively letter that was shared with friends and family – and then published in her brother's Guide to the Lakes. A woman's mountain writing thus featured within a highly influential book. But the twist is, her name was never added to the published essay. So everyone assumed it was William describing his own intrepid mountaineering! (There is no record he ever made it up Scafell Pike.)

*

Women thus found freedom, elation, and endorphins in the mountains, right from the start. From thirty-nine hour overnight endurance expeditions to solo treks, peak bagging, scrambling, snow and rock climbing, women explored, testing their limits and pioneering routes. Women also wrote extensively about their ascents in journals and letters. Due to structural inequalities, their mountain accounts were less likely to be published than men's; making their stories more ephemeral – but they were there, playing a huge and under-recognised role in the development of mountaineering culture. For, much like social media and blogs today, the women's writing had a wide readership. Pioneers like Marie Paradis, Elizabeth Smith, Ellen Weeton and Dorothy Wordsworth were up there, alongside many more forgotten women, inspiring countless more to follow in their footsteps.

Further reading:

Kerri Andrews, Wanderers: A History of Women Walking (2020)

Simon Bainbridge, Mountaineering and British Romanticism (2020)

Rebecca Brown, Women on High: Pioneers of Mountaineering (2002)

Kendal Mountain Festival

The social event of the year for outdoor people takes place across the town from 17th-20th November.

Book tickets and passes on the KENDAL MOUNTAIN FESTIVAL SITE

Helen Mort & Anna Fleming - Women Moving Mountains: on Climbing, Nature and Ambition

Sunday November 20th, 11:00am-12:00pm

Helen and Anna discuss why humans are drawn to danger and how we can find freedom in pushing our limits, examining attitudes to women who take risks, particularly once they become mothers, and questioning who their 'body' belongs to. The event will delve into what it's like to be a woman in such a male-dominated world – and the ways in which the climbing community is trying to shift that balance.

Faye Latham - British Mountaineers

Saturday 19th November, 10:15am-11:15am

Anna Fleming in conversation with award-winning writer Faye Latham, who will be talking about her new book 'British Mountaineers'. In a fascinating conversation which discusses the politics of erasure and the power of paint, Faye interrogates our relationship with a history of mountaineering which prioritises certain stories and, in so doing, rewrites and removes others entirely.

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Langdale: 10 Crags for a Lakeland Rock Apprenticeship 4 Jul

- ARTICLE: 20 Tips for More Sustainable Climbing 15 May

- INTERVIEW: Catherine Destivelle - Rock Queen 8 Mar

- ARTICLE: Top 10 Borrowdale Routes at VS and Under 22 Jan

- ARTICLE: Herstory 7: The Rise of Women Mountain Professionals 27 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Herstory 6: Lhakpa Sherpa's Long Dream of Everest 31 May, 2023

- HERSTORY: The Climbing Cholitas: Skirts to the Top for Women's Empowerment 2 May, 2023

- HERSTORY: Alison Hargreaves: Climbing Her Mountain 7 Mar, 2023

- HERSTORY: Wanda Rutkiewicz and the battle for women's climbing 13 Feb, 2023

- HERSTORY: Lady Climbers of the Long Nineteenth Century (1850-1914) 20 Dec, 2022

Comments