Technique - General approach and long-term development

Technique is the essence of climbing. It is thanks to the magic powers of movement that skilful women frequently out-perform stronger men and why many climbers achieve personal bests in their later years. When it comes to technique, there is no such thing as mastery or perfection. The quest to improve is a life-long journey and the best climbers always remain humble and open-minded. The scope for analysis is endless, with many elite boulderers feeling that they could write an entire book on the intricacies of a single boulder problem.

Few would dispute that technique is the engine of climbing performance, yet frustratingly, it always seems to be the hardest thing to improve. In the current climate of training-focused hysteria, it's easy to be distracted by campus sets, deadhangs and intervals. With training, gains are easily measured and the approach is formulaic, yet with technique the pathway will always involve shades of grey. The result is that most climbers tend to just 'go climbing' and hope that technique will take care of itself. However, with this approach there is every chance that bad habits will remain unchecked and become more deeply engrained. The answer is to take hold of the wheel and to consciously steer your technique in the required direction. I know personally that the periods when I have made a concerted effort to improve my technique have made more difference to my climbing than the times when I have focused more on training. By striving to improve our technique not only will be able to make better use of our strength and endurance (and climb harder), but we will enhance the sense of enjoyment by promoting the true artistry of climbing. This has to be a more attractive goal than simply trying to pull harder.

Technique definitions

To help us see the picture more clearly, let's start by splitting climbing technique into three main areas:

- Movement - our general climbing style and the way we execute the moves. A climber with good movement will look smooth and graceful, whereas a climber with poor movement may look tense, jerky, uncoordinated and inefficient.

- Specific techniques – the actual moves we make in climbing such as lay-backing, rock-overs or drop knees, and so on.

- Supporting tactical skills such as route reading, visualization and so on.

In this new article series for UKC, I'm going to start by looking at the overall, long-term approach to technique improvement and then we'll move on to look at movement, followed by the full spectrum of specific moves. Along the way I'll be consulting some of Britain's leading coaches and climbers for their views, starting off with Rob Russell (who has coached many British junior champions, including Kitty Wallace, Buster Martin and Molly Thompson Smith) Ian Dunn (the current British junior team coach) and David Mason, (V14 boulderer and leading performance coach).

The long-term development model

When it comes to the overall approach to technique improvement, the most important aspect is to know where you are on the development curve. There are so many different areas of climbing performance to focus on - strength, endurance, mental skills and so on, and many go wrong because they lose the path and establish the wrong priorities at certain key stages. To stay on track, it is helpful to look at a long-term development model for climbing technique.

i) Beginners – the Development phase

In the era of modern bouldering walls, countless climbers are coming unstuck because they get strong too quickly. Not only does this increase the risk of injury but it is so much harder to play catch-up with technique if your strength is way out of synch. The temptation will always be to use your arms to bail you out of trouble instead of looking for a more efficient solution. In an ideal world, for the first year or two of climbing, the focus should be on gaining mileage on easy and 'mid-level' terrain and experiencing the broadest possible repertoire of moves, holds, features, angles and so on. Put simply, this means doing lots of different routes and boulder problems, which in turn, means setting a rule that you never try anything more than a few times. This period will also enable you to build 'base' strength and endurance, so that when you move on to harder stuff, your muscles and tendons will be ready to cope with the strain.

Clearly, in the real world, few will have the discipline to stick rigidly to this model and there will always be the temptation to stray onto harder climbs, but the point is to be conscious that this should be minimised as it may do more harm than good. There are countless examples of beginners who engrain poor technique from the onset, simply by spending far too much time on hard climbs and insufficient time on easy ground. A key point to remember is that techniques are always best learnt on easier ground, where there is headspace to experiment and to steer yourself. If the boulder problem or route is too hard, you will always be tense and thrutchy, no matter how hard you tell yourself not to be.

Learning new skills is all about volume and repetition and most of us will have heard the daunting rule, which states that a minimum of a thousand hours of practice is required to show competency in a skill. The reality is that such numbers are meaningless when applied to climbing and the quality of practice clearly has a major bearing, along with the talent level of the individual. A good model for beginners is to practice in an easy bouldering environment, first with minimum variety (ie: just focus on one or two problems which emphasise a new technique, as opposed to a dozen or more), then start to try more and more different examples. The next stage is to attempt to use the same skill or skills in an easy leading environment, and finally to up the ante and increase the level of difficulty.

What the coaches say:

'The main focus for people climbing in the low and mid 6s is to get climbing. Training can come once climbing 6c or above. The biggest problem for most is just 'grabbing and pulling'. Many of these guys start to complain when a route is graded 6b+ and involves technical padding up a slabby wall and they'll say that it's 6c+ or 7a! I drill footwork till my clients can either do it or are sick of it! I love circuits on small screw-on footholds, as the footholds indoors are generally so much bigger than on rock.' Ian Dunn

'Don't get lured into the visually satisfying and physically rewarding steep style of climbing. Focus on all angles and all styles and this will prepare you in a way that you don't yet know.' Rob Russell

ii) Intermediates – the Consolidation phase

Most intermediates (those who've been climbing at least a year or two and who are operating in the F6c – 7a+ or V3 – V5 range) will hope to have gained a grasp of the full range of specific moves and be able to climb with reasonably good style on easy ground; however, the key challenge will be maintaining form under pressure. The classic ailment of the intermediate climber is to lose form as soon as the pump kicks in, especially when it is cocktailed with the fear of falling. By contrast, elite climbers often give the impression that they aren't trying hard because they are able to read sequences correctly and remain smooth and relaxed right up to the point where they fall off. As such, 'stress-proofing' of technique should be the key area of focus for most intermediates. Adrenaline wreaks havoc with technique and it's all too easy to go into 'fight or flight' mode when the chips go down. There are no fancy solutions here and the answer is simply to be mindful of resisting the ever-present temptation to pour petrol on the flames. We'll look at some more specific pointers for this later in the series. The main factor is simply spending more time dealing with the pump, so that the sensation becomes more familiar and less stressful. Climbers must be highly self-analytical and technique should remain a constant focus, so don't just switch off your brain and go into 'training mode'. Supporting tactics will include taking more leader falls to reduce anxiety. Remember that the ability to produce good form under pressure is perhaps the ultimate measure of a good climber.

Key question: should you be prepared to give up or let go in training rather than allowing bad form to creep in or should you always fight to the bitter end, even if it means sacrificing good style?

Coaches will have differing opinions on this key dilemma and it depends very much on the profile of the individual climber. For those who lack tenacity, it may not be the best ploy to provide an excuse for giving up. However, for those who are good fighters, it may be a worthwhile tactic if used strategically. In other words, on some climbs, set a rule that you're not allowed to climb badly when you get pumped and on others, allow yourself to push further, even if it means sacrificing form. Of course, the ideal is to push the red-line and to do so in good style, but the point is that you must find a way of teaching yourself. A great tactic is to use circuits rather than routes for training, as this way you will remove the falling and clipping element and be able to focus purely on maintaining form when pumped. You can then put your skills to the test on routes once you feel you've made good progress.

The effect of counter-intuition

Humans are natural climbers; however there are some aspects of climbing technique that we instinctively perform correctly and others that we naturally get wrong. For example, our default position on a steep wall is more likely to be bent arms and straight legs rather than straight arms and bent legs (unlike monkeys who seem to be better adapted in this respect). Similarly, we are naturally prone to over-reaching for handholds instead of moving our feet up first. This phenomenon is even more notable when we're under pressure – a classic example here would be rushing our footwork rather than taking those extra few seconds to place our feet well.

In short, our presumption that we can climb the best way 'by instinct' is the single biggest factor that unravels our technique. Thus, a key principle of self-coaching is to identify the main areas of technique that are counter-intuitive and to give them central focus. After all, these are not factors that can be corrected over night. There are many climbers who believe that no matter how much you practice, the most deep-set counter-intuitive responses can still manifest under pressure unless you make a conscious effort to over-ride them. I can certainly vouch for this and as evidence, I can provide some great video footage of myself holding unnecessary lock-offs and over-stretching for holds at the top of hard onsights.

iii) Elites - the Refinement phase

Many elite climbers make the mistake of losing receptiveness to technique improvements and instead place all the emphasis on training. However, for those climbing in the upper F8s or V9 and beyond, there is always scope for making micro-adjustments. The answer is to check-in with yourself for regular technique 'shake-ups', to prevent stagnation. Review the whole programme, from your movement to your route-reading and so on, in hope that you'll spot a gap or realise that one aspect of your game has slipped. Try to be free and abstract with your thinking. By definition, what you are looking for here is something that you haven't spotted before. Explore the differences between a creative, artistic approach and a scientific approach. The former may draw on analogies from other disciplines such as dance or martial arts, whereas the latter may look more into the biomechanics of specific movements. Above all else, be prepared to go back to basics in order to re-define fundamental principles.

Ballet dancers and martial artists will constantly return to the first few simple movements they were taught, to see if they can refine them. An example of this would be to perform a drill such as placing your feet quietly and accurately, to see if there is anything new to add in terms of the speed of placement, orientation of your foot and so on. The only obstacle in this process will be your ego – if you think of this as a beginner's exercise then you are missing the point. A great time to do this is during periods of injury or recuperation. Most elites consider that the only way to improve their climbing when injured is to do some cross-training and flexibility work, however there is great scope for opening up technique channels in a way that is often over-looked during periods of hard training.

Sponsored Post: La Sportiva's Pietro Dal Pra - How To Choose Your Climbing Shoes Part 1

Choosing a climbing shoe can be difficult, in the first of a series of 4 videos La Sportiva's shoe design guru Pietro Dal Pra takes a look at some of the factors you should consider.

General pointers

The following list identifies the key areas for making general improvements in your climbing technique, regardless of your level in climbing.

1. Maximum variety

Your technique will always suffer if you don't expose yourself to a range of climbing styles, so whether you're an elite who is prone to spending all their time on a woody-board or a beginner who avoids overhangs or slabs, make sure you do regular sessions where the aim is to experience as many different styles of climbing as possible; and needless to say, get out on rock whenever you can.

2. Easy, medium, hard

There are different technique lessons to be learnt from easy, mid-level and hard climbing. Easy climbing will help you learn or experiment with new techniques, mid-grade helps you consolidate and refine, and hard helps you stress-proof. All are important, although beginners should emphasise easier terrain.

3. Coach yourself as you climb

It's all about what goes on in your head while you climb and elites will be thinking about entirely different things to beginners. Try not to be distracted by the pump in your arms or the space between the clips and if you can't do this then drop the grade or train endurance on a circuit board. Spend key periods when you consciously try to climb in a certain way (for example, faster or slower, more twisted in and so on) and others when you climb more on instinct. Both approaches are important, although there's no doubt that real climbing magic can only be obtained when you're guided mainly by autopilot. However, if you are prone to making mistakes then you need to do corrective drills, using your conscious mind as a guide to re-programme your subconscious.

4. Plan your sequences

The ability to read sequences from the floor is largely a separate skill to reading them as you climb. However, the two skills bare a critical relationship to each other and the better you get at planning from the floor, the less likely you will be to make a mistake when you climb. Many climbers think they are lousy at route-reading from the floor, so they use this as an excuse not to bother. However in most cases, this is because they are going about it the wrong way. We will revisit this crucial procedure later in the series, but in brief, the main strategy for routes is simply to identify all the holds and then to visualise the hand sequence by miming it with your hands. Don't attempt to read the foot-sequence, as you're likely to confuse yourself, but it is worth identifying the holds, which are definitely for feet only (ie: small 'screw-ons' which are too poor to use with your hands). For boulder problems it may be worth guessing a few key foot sequences, but don't lock in on these too rigidly in case you guess wrong and have to change things as you climb. To be continued…

5. Analyse your mistakes and re-climb routes and problems

Most climbers simply move on from climb to climb without stopping to reflect, but it is always worth considering how you performed and better still in the case of warm-up boulder problems, re-climbing them to see if you can correct mistakes. Of course, it can be hard to know what you did wrong without the aid of video analysis or a coach; although in many cases, if you stop for a second, you'll be able to identify a general feeling that something wasn't quite right and if you climb the problem again then the light may switch on.

Going back over previously climbed territory and experimenting with something like pace can cause you to adapt in a multitude of ways. Changing pace or rhythm allows the climber to open up and move differently but still intuitively." Rob Russell

Don't just climb problems the easiest way possible for you and instead, enforce using techniques you struggle with, focus on how you are moving and try to refine these movements until they're perfect. You can also return to these climbs and experiment with different techniques, eliminating holds, using heels instead of toes or toes instead of heels and so on.' David Mason

6. Watch others and share beta

Everyone knows that one of the best ways to learn is to mimic a positive role-model, so eye-balling good climbers and watching DVDs of the pros is the way to go. However, beware that guy at the wall who thinks he's good because he can tick hard problems by campusing his way up them. It's equally easy to pick up bad mistakes from bad climbers, especially when they come disguised as good ones.

7. Use video

The camera never lies and these days there's no shame attached to filming yourself with a tripod. Even if you don't manage to catch the big send of that V10, you'll be surprised at what you might see if you've never watched yourself climb before. Look out for things like hesitation with the feet or rushed, inaccurate foot placements, excessive tension in your upper-body, jerky, excessively static or dynamic movement and so on.

8. See a coach

Historically, climbers have always been self-taught, which is why so many will develop bad habits. Of course, it's always best to have a few coaching sessions at the start of your climbing career, to help you onto the right track but that said, it's never too late to make amends. A coach may spot something in an instant that you haven't noticed in a decade and they will provide you with the tools and drills to make the necessary corrections. Most good coaches will offer bespoke, technique-focused analysis sessions and you have the option of seeing them again to look at training or other areas of performance.

9. Set goals

Having decided the main areas of focus, whether it's your movement, route reading or certain specific techniques, make a rough action plan for fixing them. For example, make a pledge to spend at least half an hour in each session, preferably when you're still feeling fresh and motivated. If you don't do this you may find that you're having the same frustrating conversations with yourself in a year's time!

Climbing has to be fun. You have to want to do it, and you need to train and climb with really good form, not doing the maximum you can in poor style. The latter just gets you injured and then you are even further away from your goals.

10. Have fun and be creative

There is no blueprint or magic formula for improving technique, so be prepared to experiment with new methods and think laterally.

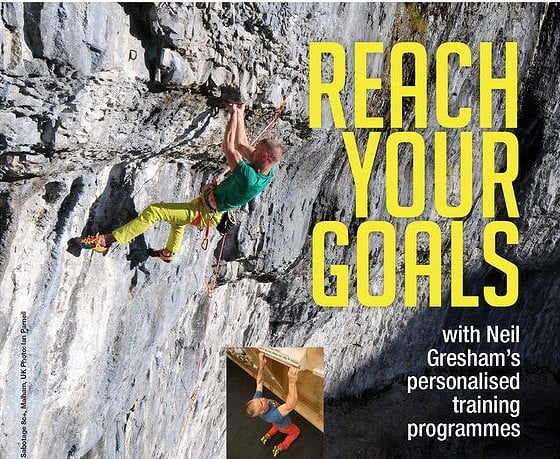

Neil Gresham is one of the early pioneers of coaching for climbing. He has climbed E10, 8c+ and WI 7 and is sponsored by La Sportiva, Petzl, Osprey and Julbo. He offers a personalised training programme service at www.neilgresham.com.

David Mason has climbed V14, flashed E8 and is sponsored by Moon and Five Ten. He is based in Sheffield and contactable on Instagram @davidmason85.

Ian Dunn is based in the North of England. He has climbed 8b and coaches the British junior team. www.coachingclimbing.com.

Rob Russell is based at the Westway in London and has been at the forefront of junior coaching in the UK for the last decade.

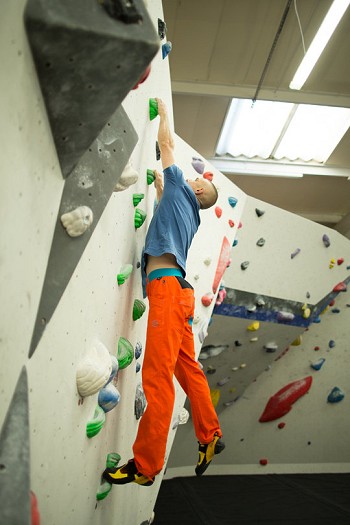

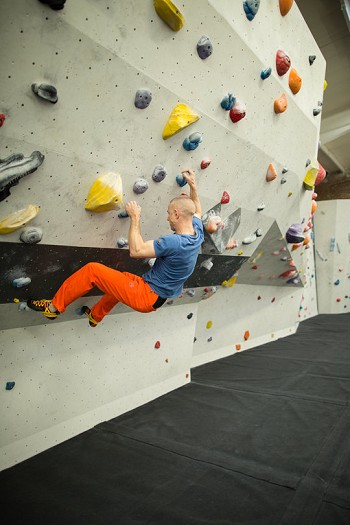

All indoor photos were taken at The Depot Manchester.

Neil Gresham is widely regarded as one of the world's leading voices in performance coaching for climbing. He has been coaching and writing regular training articles for national magazines since 1993 and has pioneered many of the methods that are used widely by coaches today. Neil is the current training columnist for UKClimbing.com and Rock & Ice in the USA.

He has climbed E10 trad, WI 7 on ice and in 2016 he climbed his first 8c+ at the age of 45 when he made the first ascent of Sabotage 8c+ at Malham Cove. Neil puts all his successes down to hard work, motivation and refinement of his game. He believes that work and family commitments don't need to limit our climbing goals provided we are focused and make the best possible use of our training time.

Key components of Neil's training programmes

- All programmes are based on response to a detailed questionnaire and are aimed at the ability level, weaknesses, strengths, goals and lifestyle constraints of each individual.

- Programmes can also be based on the results of optional benchmarking tests. See 'benchmarking' on this site.

- Programmes can be for all-round performance or geared towards different climbing styles: bouldering, sport, trad or competitions. They can also be targeted towards goals, weaknesses, trips or projects.

- You can choose between a full training programme (which includes all aspects of training) or a 'fingerboard-only' training programmes. Fingerboard programmes include advice on how to fit the sessions in with other climbing and training.