Improve Your Movement

Neil Gresham is widely regarded as one of the world's leading voices in performance coaching for climbing. He has been coaching and writing regular training articles for national magazines since 1993 and has pioneered many of the methods that are used widely by coaches today. Neil is the current training columnist for UKClimbing.com and Rock & Ice in the USA.

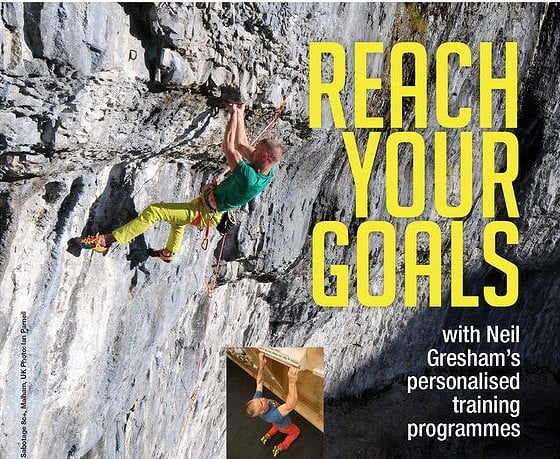

He has climbed E10 trad, WI 7 on ice and in 2016 he climbed his first 8c+ at the age of 45 when he made the first ascent of Sabotage 8c+ at Malham Cove. Neil puts all his successes down to hard work, motivation and refinement of his game. He believes that work and family commitments don't need to limit our climbing goals provided we are focused and make the best possible use of our training time.

Key components of Neil's training programmes

- All programmes are based on response to a detailed questionnaire and are aimed at the ability level, weaknesses, strengths, goals and lifestyle constraints of each individual.

- Programmes can also be based on the results of optional benchmarking tests. See 'benchmarking' on this site.

- Programmes can be for all-round performance or geared towards different climbing styles: bouldering, sport, trad or competitions. They can also be targeted towards goals, weaknesses, trips or projects.

- You can choose between a full training programme (which includes all aspects of training) or a 'fingerboard-only' training programmes. Fingerboard programmes include advice on how to fit the sessions in with other climbing and training.

When we watch good climbers in action, we are often left simply with the impression that they move well. The single biggest difference between the technique of elites and intermediates is that the elite can remain smooth, graceful and controlled when under pressure, whereas the intermediate will invariably start to sketch around when the going gets tough. Of course, climbing isn't judged on style and the only thing that matters is whether we get to the top or not, so what does it matter if we shake like a leaf? The answer is that graceful movement correlates directly to energy conserved, which in turn will allow you to climb harder and further on the same tank of gas. As such, one of the most desirable goals for any beginner or intermediate climber who wishes to improve is to develop good movement. This can seem a daunting prospect because fundamentally, good movement is so difficult to define and quantify.

In general, climbers know how to exchange beta for different types of movement, but when it comes to improving our climbing style, the best approach would seem to be something of a mystery. A popular myth is that this will take care of itself if we simply do more climbing, yet if we have bad habits, all that will happen is that they will become more deeply engrained. To add to the challenge, there is no precise blueprint for perfect climbing movement, and there is much scope for individual interpretation. Over the years, the best climbers have often been the ones who have developed their own unique signature style. Whether it's Johnny Dawes in the 80s or Adam Ondra in the present day, neither were typical of the stereotype for good climbing movement, yet both developed a seemingly magical movement style which played to their physical attributes. This may confuse matters further; however, don't be deterred, there is a simple and practical model, which can be used by all climbers in order to facilitate continuous improvement of movement skills.

Movement Drills

The warm-up is the best time to improve climbing movement because we feel mentally and physically fresh and the climbing is sufficiently easy so as to allow the headspace for experimentation. The idea is to focus on key components of movement during warm-up climbs, first individually and then in combination. The aim is to establish a template for perfect movement on easy ground and then to attempt to maintain this form and make it 'stress-proof' on harder climbs. For so many climbers, the warm-up is a chore and something to be rushed through, so that you can move on to harder stuff. But if you dial into the right headspace, your warm-up may end up doing as much, if not more good for your climbing than the harder climbs or training sets that you do in the remainder of the session. No matter how hard you climb, don't make the mistake of thinking that movement drills are too basic for you. Ask yourself if you ever bang your feet or forget to breathe and if so then it pays to keep an open mind. Movement drills provide a bottomless pit for self-discovery and improvement in climbing, so don't allow your ego to make you miss out!

Key benefits of performing movement drills

Continuous technique monitoring

Movement drills can be used to monitor your technique throughout the year. For example, after time out or worse still, 'training focused' periods, when you've mainly been campusing and fingerboarding, you will notice that you can't perform the drills well and so, can use them to get your movement back up to standard. Initially, you may struggle to know whether you're doing the drills well or not, but after a while you can tell by feeling alone.

Improved body awareness

Movement drills will help you to gain an awareness of all the relevant chains of muscles and how they should feel when you're climbing. In turn, this will help you to relax muscles that you don't need and to maintain minimal tension in the ones that you do need. Climbing on rock isn't just about pulling off hard moves and battling with sustained sequences. The ability to conserve energy on easy ground is a valuable skill, which many climbers underestimate. It doesn't matter how strong or fit you are if you climb the lower, easy section badly you won't have the reserves to pull off the crux.

Mental control on difficult ground

Perhaps the most important skill in climbing is the ability to stay calm and focused when you're either scared, pumped or both. The greatest power of movement drills is that they can be used to help you stave off the urge to panic and start tensing up when you get into a high-stress situation. Or if it's too late and you've already hit that point, then the drills can be used to help you calm down, regain composure and get your technique back on track, to give you the best chance of finishing the climb.

Mental preparation for sessions

One of the most common ways that climbers under-perform is that they make mistakes as a result of not focusing during their warm-up. When we arrive at the climbing wall we are often stressed and distracted by the day's tasks. For those who don't have the time or inclination to sit down and mediate (IE: most people), movement drills provide a far more practical means of helping us to de-stress and to focus on relevant skills so that our technique is sharp and our head is 'in the zone' for harder climbs.

Increased enjoyment of the warm-up

Easy routes or boulder problems can be boring unless you challenge yourself mentally. Movement drills provide welcome stimulation and help stave off the temptation to rush the warm-up.

i) Pulse Raiser (3 – 5 mins) EG: Burpess, skipping, jog-on-the-spot.

ii) Dynamic mobility exercises (3 – 5 mins)

EG: Shoulder circles, hip-circles, leg-swings.

iii) Stretch-band work (3 – 5 mins) EG: rotator-cuff, shoulder raises etc.

iii) Easy climbing with movement drills, EG: traverses, circuits, routes, 'up-down-ups' on easy boulders, and/or random climbing; EG: 2 mins on, 2 mins off x 3 (12 mins total).

iv) Progression of harder climbing sequences (ie: build up steadily through the grades on routes, circuits or boulders, until you reach peak level for the session) eg: 25 - 30 mins. Try to maintain form using the hit-points from the movement drills.

Movement drill list

The selected drills represent generic components, which are common to virtually all climbing situations, as opposed to specific moves such as bridging, flagging, drop-knees and so-on.

1) Precise footwork

2) Straight arms, with a relaxed grip

3) Fluid style

4) Increase pace

5) Deep, regular, breathing

The method:

Having done your pulse raiser and some mobility exercises, move on to easy warm-up climbs and use these for performing the drills. The aim is simply to start with the first drill – 'precise footwork' and to aim to perform this perfectly. It's worth videoing yourself periodically, however, this is by no means essential. Once you are aware of the drills, they are surprisingly black-and-white and you can usually tell whether you're performing them well or not.

Many beginners and low-intermediates will find the first footwork drill to be more than challenging for the first few sessions of practice, so don't be tempted to rush on to the next drill too soon. You should only move on to a new drill when you feel that you are performing the previous drill pretty well. The key is that when you add a new drill, you still need to maintain form in the previous drill. In other words, it's no good trying to add the straight-arms drill if this means that you start banging your feet. By the time you start attempting to do three or four drills simultaneously, you should feel that you are testing your multitasking skills to the limit.

For best results do stints of 1 - 3 minutes with approximately 2 mins rest in between and do 3 or 4 total. Avoid doing single boulder problems and jumping off, as you don't really get a chance to get into your flow. If you're warming up on boulder problems then a good tactic is to climb up a problem and then down, using all colours or an easier problem, and then to climb up again. A good tactic for the first two drills is to find an easy, vertical part of the bouldering wall, or a traversing wall and simply to 'rainbow' and climb around at random, as this enables you to focus more on the drills and less on reading the sequences, and it also means you can pick the most user-friendly holds. Then for your third and fourth stint, you can follow easy colour-coded sequences, whether routes, problems or circuits. Keep the grade as low as possible for the first 2 climbs and maybe increase it very slightly for the third or fourth. The goal is for zero pump, so don't be tempted to start scaling up through the grades too soon, or you won't be able to perform the drills correctly.

When attempting to combine more than two or three drills, it helps to repeat them in your head on a loop; for example "Precise feet, straight arms, relaxed grip, fluid moves, pace, precise feet, straight arms, repeat, repeat". You can switch commands every move or every second move, thus using the rhythm of your climbing as a guide. Higher-level climbers can group drills together and, for example, do precise feet and straight arms combined on their first climb and then add the second two drills on their second climb, and so on. When you move on to harder warm-up climbs in the session, try to maintain form using the hit-points from the movement drills. In doing this, you accept, of course, that you won't manage this all the time, but the important thing is to try.

1) Precise footwork

As seen in the early articles in this series, precise, accurate footwork provides the foundation of all climbing movement. You can never hope to perform a move with maximum efficiency if you start that move with poor foot placement. The more accurate you are with your feet, the less likely you will be to over-grip and the more energy you'll save in your forearms. As such it makes sense to start your movement drills with a focus on footwork. If you're climbing at random, a good ploy is to select large handholds and smaller footholds, such as screw-ons, as this will test your accuracy more effectively than standing on jugs. However, it's vital to apply the same level of care and attention to all footholds, even larger ones, as this will help you hone the control and accuracy for smaller holds. This is especially important to assist the transition from climbing indoors to climbing outside, where the footholds are always much poorer. Remember this drill is not so much about practising different types of foot placement (edging, smearing and so on) but simply how to place your feet with greater control.

i) Silent

If you can hear your feet then this is a clear sign that your foot placements are rushed, inaccurate and generally lacking in control. To correct this, slow down as you approach the foothold and hover your toe over it for a second before placing it. This may feel contrived, unnatural and frustrating at first, but it represents the best single correction you will ever make to your climbing style.

ii) No scuff

No climber likes to think that they scuff their feet, but if we're being honest, those tell-tale wear points on the tips of our shoes are the proof that we often slide our toes down the wall. Make a rule that you're not even allowed to touch the panel above the foothold.

iii) First time

Most climbers quickly eliminate the habit of blatantly sketching with their feet and re-adjusting, however, if we look carefully we may realise that we rarely make clean, first-time contact with every foothold and are prone to 'double-touching'. The re-adjustment is sometimes barely noticeable and may only be the tiniest shuffle, but the goal is to eliminate it completely and make a crisp, first-time contact.

iv) No test

If you place your foot with total control and accuracy on a small foothold then there is simply no need to keep testing it. This nervous habit only serves to waste time and potentially, dislodge the initial foot-placement. One-little, controlled pre-test is ok, but if your knee is bouncing up and down then you need to stop this.

v) Eye on the ball!

So many climbers will look up towards the next handhold, just at the crucial moment when their foot is making contact with a foothold. Page one is to keep your eye on your foot until it is securely in position.

A secondary benefit of performing footwork drills is that they will improve your balance. Sloppy footwork is often caused by attempting to move our feet when we're off-balance. However, if you set a rule that you're not allowed to bang your foot on to the next hold then this will force you to be mindful of hip positioning and to manoeuvre your body into balance positions.

2) Straight arms, relaxed grip

As we noted in the previous article on posture, when climbing on steep walls, our natural instinct is to straighten our legs and bend our arms, especially when we're pumped and scared. This is partly because humans instinctively 'stand up' (which forces us into a bent-arm position) and also, pulling ourselves into the wall may provide the perception of security. This causes us to squander energy in abundance, mainly by restricting the circulation in our forearms, which causes the pump to set in. When locking-off and stretching high for clips on the lower part of a route, you won't feel it tiring you at the time but fatigue will catch up with you later! Of course, this is mainly relevant to routes; nonetheless, when bouldering it still doesn't make sense to over-use your strength.

The correct position is to keep the arms as straight as possible, with shoulders 'engaged', hips centred directly below and legs bent. Of course, you will still need to bend your arms at times, but the idea is to train yourself to do this as minimally as possible.

Alternatively, if you only have one foothold then use the outside edge and smear your other foot flat against the wall and twist in. A further option is to keep your hips parallel and turn both knees out into a 'frog' position.

As such this drill will also have a powerful knock-on effect to improving your balance, as you won't be able to attain stability simply by pulling yourself into the wall and will become more aware of the subtleties of foothold selection and hip positioning.

Relax your grip!:

Linked closely with the need to keep our arms straighter, is the constant challenge of avoiding over-gripping. Most climbers simply build in too high a safety margin with gripping, especially when they're scared! Instead, try to relax your grip by dragging your fingers over the holds and relying on friction in order to grip more passively. You simply can not drill this enough, and it is one of the first things that evades us in high-stress climbing situations. For best results, perform this drill on gently overhanging or vertical walls, as it is less relevant to slabs.

3) Fluid movement

In most cases, climbing essentially involves moving from point-to-point between fixed positions. We are invariably most efficient when we flow through these fixed positions, rather than stopping and holding them. This is simply because when we pause we are losing momentum and our muscles become more tense with prolonged static contractions. One of the reasons we can climb harder when redpointing is because we are familiar with moves and can flow through them, whereas when onsighting, we adopt a more punctuated style; hence, the best onsighters always look as if they're redpointing!

Needless to say, the ability to flow through moves is linked directly to the ability to read sequences quickly, and this is something that only comes with practice. However, the ability to move fluidly can, to a large degree, be isolated and trained separately, either by 'rainbowing' (climbing at random using any colour) or climbing easy routes, circuits or problems that you either know well or which are very easy to read. Higher-level climbers can practice on lead, whereas most intermediates will probably get more benefit from using a traversing wall, circuit board or auto-belay, as the clips can distract you and break your flow.

The aim is simply to climb as fluidly and continuously as possible. You can use imagery to program your movement; for example, imagine yourself climbing like a martial artist performing a kata. You may find that you need to glance ahead to plan the next move whilst executing the current one (though never take your eyes off your feet when placing them). You will have to climb very slowly at first. It's easy to fall into the trap of thinking that fluid means fast but if you rush you will find yourself making sequencing mistakes and your footwork will regress. As such, this is a relatively advanced drill, which shouldn't be attempted by beginners. For those climbing in the F6s, it is far more important to focus on making solid, stable, balanced body shapes between each move and to gain an awareness of how those fixed positions should feel, rather than being distracted by the pressure of having to flow through.

4) Increase Pace

A further reason we are able to climb harder on redpoint, in comparison with onsighting is simply that we move faster. When it comes to steep, sustained sport climbing and bouldering, speed is efficiency, provided you don't rush and make sequencing mistakes or sacrifice good form. Climbers are prone to dawdling for a host of reasons, ranging from fear of falling to lack of faith in route-reading to being too fit for their own good! A key role of this drill is to help you explore the tipping point of climbing pace. The aim is simply to speed up, slightly, say by 5 - 10% initially, without compromising on the first three drills. Whilst doing this, note the difference in feel and mentality between a slow, 'defensive' climbing style and a fast 'attacking' style. The key is to develop the skill of adjusting your pace to the terrain; IE: attack and climb fast when it's hard and defend (relax your muscles, move slowly and use rests) when it's easy. This is a relatively advanced drill, so don't attempt it unless you're onsighting in the high F6s and can perform the first 3 drills to a good standard. Even if you're climbing high 7s and 8s, don't do try to climb fast until your third or fourth warm-up climb, as you will struggle to switch-on the required level of coordination and may risk injury.

5) Deep, regular breathing

For those who've kept up so far, this final drill proves to be the tipping point for all but the very best climbers. Correct breathing technique for climbing is something that you can only hope to improve and never master. Most climbers feel that there is enough to worry about when climbing without adding breathing to the list, and this is precisely why we tend to breathe erratically and inefficiently. The usual pattern is to hold our breath during the hard sections and then to gasp on the rests. If we were to breathe the same way when running or cycling then we wouldn't get far! Not only will correct breathing technique help us to minimize fatigue by delivering oxygen to the muscles, but it will also help us to control anxiety (fast, erratic breathing will raise adrenaline levels, whereas deep, regular breathing will lower them). Entire books have been written on breathing technique, but if we complicate this topic we will make the situation worse! The key is simply to remember to breathe deeply and regularly!

The key is to avoid taking thin, shallow breaths by sucking air through your mouth and instead to take breathe from the diaphragm. One way to do this is to focus on completely emptying your lungs when you exhale, as this will trigger a diaphragm breath as a reflex response. Another method is to breathe in through the nose and to exhale through the mouth, but this is probably too much detail already!

Maintaining good breathing whilst climbing is the ultimate case of patting your head and rubbing your stomach. We are so deeply programmed to breathe subconsciously, that our conscious mind finds it the easiest thing to ignore. And even when we do remember, it's virtually impossible to think consciously about breathing and work out moves at the same time, so the best we can hope for is to work out a move, then remember to breathe, then work out the next move, then breathe, and so on, as opposed to thinking about both things simultaneously! Clearly, if you over-cook the focus on breathing then your route-reading and general coordination will implode and you'll make crucial errors. This ultimate test is all about knowing how to divide up your attention and switch emphasis between the different drills.

My early experiences with movement drills

When I first started coaching full time in London in the mid-1990s, the main thing I noticed was that so many beginner and intermediate climbers didn't seem to move well on the wall. At that point in time, my approach to coaching technique was merely to 'talk beta' and demonstrate specific moves, such as flags, drop-knees and so on, but I had no idea how to teach climbers to move better. This prompted me to see how things were done in other disciplines that were similar to climbing, so I attended a few dance and martial arts classes. The common theme was that the high-level performers always started their warm-ups by drilling very basic moves such as leg-lifts, before moving on to more complex routines. I figured that the same methodology could be applied to climbing, so I came up with a list of drills and started testing them on my clients and in my own warm-ups. Sure enough, after a bit of tweaking and refinement, I noticed dramatic results, both in my own climbing and also in my clients. Around this time I made a film (Masterclass Part 1) that documented the methodology, and over the years I have received countless feedback from climbers who have found that movement drills have transformed their technique. This was an exciting period for coaching and no doubt other coaches were refining similar methodology around this time.

Summary

The more frequently you practice movement drills the more powerful an effect they will have on your climbing and there's no reason why you shouldn't do them every time you climb. Don't worry about your pals thinking that you're taking things too seriously as they need never know what you're doing! A final word of advice is not to rush the process of working your way through the list of drills. Play the long game and take the time to get each one really dialled-in before moving on. Remember that you can use movement drills for monitoring and improving technique for the rest of your entire climbing career.