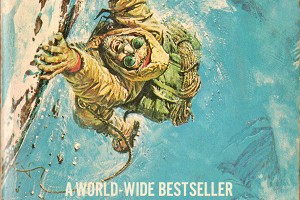

"Those who survived WWI emerged with a more accepting attitude to risk, injury and sudden death". George Mallory might (or might not) have been the first man up Everest. So what drove him to his death? This illuminating biography, an early winner of the Boardman-Tasker award, offers insight on one of the finest climbers of his generation, says Ronald Turnbull.

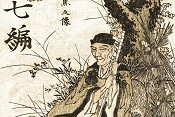

Over one hundred years ago, George Mallory and Sandy Irvine died high on the Everest's north-east ridge. Did they make it to the summit? It's an interesting question, but one which will probably never be answered. However, an even more interesting one: who was this man Mallory anyway? And what was it that drove him, over three separate attempts, to his death?

George Mallory's upbringing was odd already. His mother Annie was a wild child, with a dead father and uninvolved mother; his father, a respectable vicar, was manoeuvred into the marriage by Annie's family. All of us parents must position ourselves on a spectrum between protection and adventure: raised by Annie Mallory, George's lever tilted towards adventure. But then he was shoved off into the English boarding-school system.

So how do we know all this? About George Mallory's parent's marital problems, his maternal granny's preoccupation with Good Works among the mill girls of Derby? It's from the detailed, readable, and illuminating biography by Peter and Leni Gillman. It's a close account of the social milieu of the last generation of climbers drawn mostly from upper-middle-class academics. But it's also a cool and journalistic look at what made Mallory himself so special: the life choices that would eventually lead him to death on Everest.

'The Wildest Dream' was one of the first winners of the Boardman-Tasker Award, and Taylor Swift even lifted its title for one of her most sultry songs, found on her 2012 album 1989. (Note for non-Swifties: that's her album named 1989, ie five years later than George Orwell's book, but released in the year 2014. Got it now?) The video features Taylor snuggled up with an animatronic lion.

It would be rather grim to see others, without me, engaged in conquering the summit...

Back to Mallory. It's widely realised that old-style public school life, with its single-sex environment and oppressive hierarchical structure, is alienating and damaging. George Mallory himself described himself and his schoolmates as "disastrously ill equipped for making the best of life". But at the same time, at prep school and then Winchester, he absolutely loved it… And he was taken off to the Alps by a teacher similarly well tilted towards the 'adventurous' end of the spectrum, climbing through stonefall and storms onto the Grand Combin and Mont Blanc. Even then in the 1910s that teacher, George Irvine, was criticised by the climbing establishment for exposing schoolboys to such a high level of danger: ten years later, two of them would die on L'Eveque above Arolla.

"He's so tall, and handsome as hell" – oh, sorry, that's the Taylor Swift version… "A head like a Grecian God" – that's George Mallory as described by Virginia Woolf. University led to a different sort of adventure, on the edges of the gay intellectual circles of Cambridge and the Bloomsbury Group at a time when gay sex was a crime attracting serious prison. (Oscar Wilde had received 2 years hard labour just 10 years before.)

It seems odd, today, when top climbers are single-mindedly climbers and nothing much else, this intersection between the Cambridge intellectuals, the Bloomsbury Group, and Geoffrey Winthrop Young's climbing circle at Pen-y-Pass on the slopes of Snowdon. George was painted and also photographed in the nude by Duncan Grant, courted by James and Lytton Strachey and John Maynard Keynes, and appears as 'George' in EM Forster's 'Room with a View'. Meanwhile he was also being courted by Geoffrey Winthrop Young, the leading climber before the First World War. "Young pressed himself on Mallory," the Gillmans write, in an image that's appropriate but perhaps more intimate than they intended.

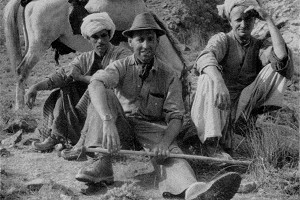

As a climber Mallory was the most talented of the GWY circle, leading up to VS standard with minimal protection. Even back in 1911, Dr Karl Blodig, the first man to knock off all the 4000-ers of the Alps, recognised that "that young man will not be alive for long." Mallory's friends didn't agree. He was "prudent according to his own standards" even if those were "not the standards of ordinary rock-climbers".

His Cambridge degree meant that, without further training, he could become a teacher at Charterhouse public school, covering maths, history, French and Latin. His teaching style was relaxed and liberal: one pupil, the future poet Robert Graves, got taken up Snowdon and considered Mallory the best teacher he ever had. (Is Graves falling into obscurity? He's the author of one of the best WW1 memoirs Goodbye to All That and the novel I Claudius, made into a successful TV series in the 1970s starring Everest-attempter Brian Blessed.)

Then comes World War One. As a maths teacher Mallory was assigned to the artillery, meaning that his war was marginally less dangerous and uncomfortable than it would have been in the trenches a mile or two further forward. Of 60 Pen-y-Pass climbers in Winthrop Young's circle, 23 died and 11 were wounded, including GWY's own lost left leg. Those like Mallory who survived emerged with a more accepting attitude to risk, injury and sudden death.

All of which made him a natural choice for the inter-war Everest expeditions.

1921 saw him discovering the East Rongbuck Glacier (it wasn't obvious) and climbing to the North Col at 7500m. In 1922, with Edward Norton and Howard Somervell, he climbed without oxygen to 8100m on the north ridge. 1924 saw him caught between the "competing passions" mentioned on the cover of Wildest Dream's hardback edition. On the one hand, a congenial and well paid job as adult education lecturer; his loving, and loved, wife Ruth and young family; a handsome new house near Cambridge to do up; and a loyal group of climbing companions for Wales and the Alps. Against that: "It would be rather grim to see others, without me, engaged in conquering the summit." Everest won out.

The weather this time was much worse. A month of deep snow and storms saw them no higher than the North Col. But at the start of June, a weather window opened up.

With just a few days left before the monsoon, Mallory and Alexander Irvine, climbing with oxygen, head up from the North Col. On 8th June they set out from Camp VI at 8100m. Just after midday, expedition member Noel Odell spots them, in a clearing of the cloud, somewhere high on the crest of the North-East Ridge, at around 8500m level. This would put them still several hours short of the summit and probably still below the difficult rock pitch of the Second Step. Seventy-five years later, Mallory's body was found at 8150m, below the North-East Ridge. Sandy Irvine's one is still missing, along with the camera that might have recorded a summit photo, supposing there were one.

"Someday when you leave me, I bet these memories follow you around." Taylor Swift again, but could equally be poor Ruth Turner, already deprived of her man by the War and by Everest for well over half their married life.

Since then and up to January 2024, according to statistics compiled by Alan Arvette 325 more people have died on Everest: that's about one in 100 of those who attempt the mountain, or a death for every 37 summiteers. Making Everest one of the less lethal of the 8000-ers.

Meanwhile, George Mallory leaves behind the shortest mountain quote of all time: the famous "because it's there". Peter and Leni's biography also fleshes that one out a bit.

So did George Mallory or Sandy Irvine or both get to the top of Everest 29 years before Hillary and Tenzing? To save you reading the Gillmans' book (though you should anyway) Ronald has summed up all the available evidence on his Substack weekly essay.

- Mountain Literature Classics: Harry Griffin, the alternative Wainwright 12 Jun

- Mountain Literature Classics: WH Auden's In Praise of Limestone 2 Dec, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog 15 Feb, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: South Col by Wilfrid Noyce 9 Jan, 2024

- Mountain Literature Classics: Free Solo with Alex Honnold 29 Nov, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: That Untravelled World by Eric Shipton 3 Aug, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight 4 May, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Menlove 9 Mar, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North 12 Jan, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Conquistadors of the Useless by Lionel Terray 17 Nov, 2022

Comments