Mick Ward reflects on the life and climbs of a Yorkshireman and gritstone pioneer...

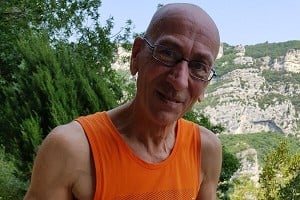

Allan Austin, who recently died at the age of 90, climbed about 700 new routes. He was noted for his boldness and his fierce commitment to climbing ethics.

"I always said you were the best climber to come out of Yorkshire. But then, they're never much good, are they?" (Joe Brown)

Lancashire breeds dark horses. It's probably all those gloomy quarries. Venture tentatively round some vegetated corner near Bolton and, before you know it, you'll have stumbled across yet another genius climber you've never even heard of. Someone called Hank, or Ian, or Gaz, or Ryan.

But Yorkshire's different. Very public crags. Look at Gordale, Kilnsey, Malham – overhanging sneers, all of 'em. "Think you're any good? Well you're soon going to find out. And chances are you'll be scurrying home with your tail firmly between your legs."

Yorkshire always had heroes. Fred Botterill soloing the first ascent of his eponymous slab on Scafell, ice axe in hand, doffing his cap to a lady below. Claude Frankland with his eponymous green crack at Almscliff.

The Yorkshire wart. A geological oddity. Almscliff is visible for miles around. Visibly sneering at you.

Stepped into a cow pat on the way in? Just a taste of the humiliation in store. Get used to it, mate.

"As for Dolphin, we all regarded him as being a gentleman. You can't say more than that; honest, straightforward."

Yorkshire breeds heroes - none more iconic than Arthur Rhodes Dolphin, a slim, blonde haired, ethereal runner cum climber. In Langdale, Dolphin climbed Kipling Groove, pride of the valley, so named because it was 'ruddy 'ard'. (He had a penchant for weak puns.) At Almscliff, he made serious inroads into the intimidating North West Face. Today his routes such as Great Western and Overhanging Groove are a delight. 70 years ago, it was a very different matter.

But then, as so often happens, fate cruelly intervened. Harold Drasdo rhetorically asked: "Where were you when Arthur Dolphin died?" And everyone instantly knew.

Time was frozen. Dank tendrils of mist swirled menacingly around the North West Face of Almscliff. Yorkshire brooded - waiting for a new hero.

"When we started, there were just no runners. The VSs were never 'led' - they were soloed."

Allan Austin, stalwart Bradfordian, came relatively late to climbing, in his early twenties. He'd just done his National Service in Hong Kong. His mother got him fixed up with a YMC (Yorkshire Mountaineering Club) course. Did she have any idea what lay in store? I very much doubt it.

How do hedgehogs make love? Carefully. Very carefully. And before the 1970s introduction of wires, then cams, people went up the grades very carefully indeed. Fall off a Severe and you might die. People did.

"When I first met you in 1956, I thought this guy will either win fame - or end up lame!" (Dennis Gray)

But Austin? Nope. He went at it like the proverbial bull at a gate. Interestingly, in the Billy Bunter books, the Yorkshire stalwart is named Johnny Bull.

Although Austin was roughly the same age as Brown and Whillans, they'd already been climbing for the best part of a decade. 1956, Austin's first proper year of climbing, marked the zenith of the Brown-Whillans partnership: routes like The Thing, Quietus, Rasp, Erosion Groove Direct (all E2) and the chop route Taurus (E4). These routes were a step up from the 'easier' Extremes (about E1). This was some 20 years before E grades were invented, so XS (Extremely Severe) already covered at least four full grades.

Never mind that Austin was a beginner, he was quickly out there struggling in the company of Brown and Whillans. He hadn't yet got technique – but he found that brute strength and ignorance could get you a very long way.

"The best route I ever did was in Ireland in Donegal, a 550-foot HVS."

In 1956 he went to Ireland, with talented climber, lifelong friend, Brian Evans and Jenny Ruffe, his future wife. They did the third ascent of Ireland's hardest route, Spillikin Ridge. At the time, it was probably about E1. A decade later, the eponymous spillikin (a huge, detached flake) blew away in the wind and the route became harder (E3).

(Please note. You can't reasonably compare ascents of routes then with ascents of them now. Without wires or cams, they'd feel roughly two grades harder. There's a big difference between a runner every eight feet and one every 30 feet – with skeletal (or no) descriptions and possibly loose rock, mud, grass, etc. thrown in.)

1957 saw a return to Ireland with the same team and Brian Fuller (Fred the Ted). They did the first ascent of the magnificent Nightshade (then HVS with aid, now free at about E2) in the Poisoned Glen. The previous day they'd done the first ascent of the nearby Slanting Grooves (VS). These were – and are – serious routes, in a remote setting.

"High Street is a hell of a line, isn't it?"

But it was Yorkshire that would become Austin's fiefdom. It made sense; it was on his doorstep. With Eric Metcalfe (allegedly known as 'Matey' because he wasn't), Austin set about developing venues such as the character-forming Baildon Bank. At Crookrise, he established a new testpiece, 'The Shelf' (E2). At Ilkley, he created the first of his trio of psychological masterpieces. The wonderfully named 'High Street' takes a wall of withering blankness, starting from a ledge system half-way up the crag. Rarely done, even today (it's still serious), the present grading of E3 fully takes into account modern protection. If Austin had come off High Street, he'd have incurred life-changing injuries on the ledges, before tumbling down them, then hitting the quarry floor. That fall just doesn't bear thinking about.

"Yes, we never wasted a day. I once got 100 routes in at Ilkley, after tea."

But… Ilkley was Ilkley. The centrepiece of Yorkshire gritstone would always be Almscliff, where Dolphin had already raised the bar to a high level. To become the undisputed king of Yorkshire climbing, Austin would have to make his mark at the crag that mattered most. Not only that. He would have to make his mark on the part of the crag that mattered most – the North West Face.

"I was laid out unconscious on the floor. Nobody came to look at me. As I opened my eyes, nobody said a bloody word…I was shaken up, but we still carried on climbing that evening."

Going ground-up on the direct start to Great Western took boldness a stage further. All went well… until it didn't. To the horror of onlookers, Austin plunged into the boulders at the base, somehow managing to survive unscathed. How he didn't break every bone in his body must remain an eternal mystery.

What to do? One obvious solution was repeated top roping. Another solution would have been to fiddle a chockstone into one of the cracks. Another solution would have been to combine these approaches.

But did Austin resort to that kind of malarkey? Did he hell! Instead he went back and soloed the damn thing. Today, with wires and cams, Western Front is regarded as a relatively safe – albeit highly technical – E3, a jamming testpiece.

"There's never been that many men who could make a hard move 80 feet out. Never. There probably isn't today. It were hard doing it. And of course it was worth it."

But Austin's ascent, solo – on a line where he'd fallen, decked out and should have died? Going back up again for more? This went beyond High Street. It went beyond Preston on Suicide Wall, or Brown on The Thing, or Whillans on Taurus. This took climbing somewhere else — somewhere nobody wanted to think about.

And, lest anybody fondly speculate that Austin was just some kind of local performer (Ireland notwithstanding), on Cloggy he freed White Slab E4 onsight in 1958; a big line on a big, intimidating cliff, just a couple of years after starting to climb. Not so shabby now, is it?

Brown and Whillans may have garnered the lions' share of the plaudits. But if there had been a prize for boldness, there's no doubt as to where it should have gone.

Yet not even Western Front was enough. Because if Austin was to become be the undisputed king of Yorkshire climbing, there was one monster above all others which simply had to be slain. And he only had to walk a few yards from Western Front to find it. Famously, he did.

"They used to come once to Almscliff and never come back."

Dolphin had named the expanse right of Long Chimney, The Wall of Horrors. Decades later, Paul Willams would memorably dub it: 'The Great Wall of grit'. Amazingly, shortly before his death in 1953, Dolphin had top-roped it. He speculated that one day someone would come along good enough to do the first ascent on sight. Looking back with inevitable historical perspective, this was as romantic as it was unrealistic.

After his harrowing experience on Western Front, wisely Austin resorted to top-rope practice – allegedly a lot. There are two cruxes on Wall of Horrors: a boulder problem start and getting past the break at half-height. Failure on the second crux was unthinkable without a runner – which Austin didn't have.

"On the entire North West Face of Almscliff we knew where there were three runners; on that whole wall. Imagine that."

In the end, he soloed it. A rope would have been no earthly use to him. Allegedly he'd found the top crux very hard. I can't begin to imagine the commitment of going for something so seemingly close to one's limit. Austin's ascent of Wall of Horrors, at the dawn of the 1960s, marked the climax of his climbing career. It was rumoured that Whillans had been up to the break but traversed off into Long Chimney. It was rumoured that Brown had also reached the break but retreated (presumably by the same method) to get back down and give first aid to an injured climber. Brown and/or Whillans may have started Wall of Horrors, but it was Austin who finished it.

"The Wall of Horrors gave me the most pleasure. It had been a long-standing problem and the scene of many previous attempts."

In the years to come, the reputation of Wall of Horrors reached mythical proportions. For most of the 1960s it was probably the hardest route in Britain. In 1964 Tony Nicholls made the second ascent. Nic was cast in the same heroic mould as Austin. But he was a Lancastrian – and you remember what we said right at the beginning about dark horses? Sadly, his ascent went almost unnoticed.

In 1970 John Syrett made the third ascent, believing it to be the second. His friend, John Stainforth, shot a photo sequence. The famous image – of Syrett crouched at the break – bestowed instant and enduring iconic status on an almost unbearably gifted climber.

"What I did was balance the risk of what I was looking at against my judgement and ability. Now I think that's stupidity really. But all young men think that."

With Wall of Horrors, Austin completed his triple crown. However unfairly, High Street would be forgotten. People took heed of Western Front. But it was Wall of Horrors which would forever define him.

Austin became the undisputed king of Yorkshire climbing. With routes such as Gimmer String (E1) and the majestic Astra (E2) he also became the undisputed king of Langdale climbing. Sure, Brown and Whillans were far more famous – but 'ranting Allan Austin' had his own distinctive place in the pantheon of stars.

"It is just nationalism, I suppose. Everyone likes to believe that they come from a special area."

Yet in Yorkshire, perhaps more so than anywhere, no king could possibly go unchallenged. In the early 1960s, two young lads, the Barley brothers, emerged as the first threats to Austin's crown. On grit, The Creation (E2) and The Beatnik (E3) were significant. But on limestone, at Malham, they demonstrated clear supremacy with Wombat (E2), Carnage (E2) and The Macabre (E3). Even in the mid-1970s, these routes retained a huge reputation.

"You know how hard a route is. The hard routes were big routes and what we meant by that were routes that you could get chopped on."

However, a problem remained. I can't remember what the Barleys' grit routes were then graded. But for years their Malham routes got HVS, when they were clearly much harder. These were fairly big lines, with loose rock and not much protection. You could hurt yourself. Yet in the YMC guidebook they stolidly remained HVS.

Worse was to come. In the Foot and Mouth epidemic of 1967, one of the few places you could climb was the terminally loose Langcliffe quarry. As my old mate John Lumb wryly noted, it was conveniently close to the graveyard. Austin and others developed it. The YMC guidebook grades were laughable. Tabula Rosa is the most terrifying route I've ever done. Probably fewer people have led it than have stood on the moon. And the grade? HVS.

"It has been years since I was frightened that I was going to be killed."

At a gathering of the infamous Phoenix Club, John Lumb wailed to Pete Livesey, "But they're not HVS!" Pete smiled ruefully. "I know, I know…" He calmed John down, as you would soothe some poor kid who's just discovered that Father Christmas is a Tory MP.

The undergrading carried on, became a local joke, encouraged more undergrading. John Syrett soloed Propellor Wall at Ilkley and jestingly gave it VS. It subsequently went up to E5, (though it's now settled down a little).

It always seemed to me that the undergrading was there to psyche people out – to demonstrate clear Yorkshire supremacy – a kind of, "If you can't take it, then sod off back home!"

The 1970s dawned with Austin (rightfully) gracing the front cover of the gritstone guide. It looks as though he's inching up a blank, protection-less wall. But you could hang an elephant off those jams on Dolphin's superb route, Beeline. And if you really wanted to, you could have dropped in runners at will. Was it the same motivation, to somehow keep Yorkshire sacrosanct? "If you can't take it, then sod off back home!"

"I decided years ago that if you were not opinionated in an article, then it was not worth reading, so I deliberately intended to annoy the reader."

John Barker, on an early ascent of Whillans' Forked Lightning Crack. A very different proposition indeed, before cams were invented. John had no big hexes either. He just threw a sling around an ancient bird's nest and hoped there was a chockstone beneath it.

In the early 1970s, Dave Cook wrote a brilliant article entitled 'The Sombre Face of Yorkshire Climbing'. It appeared in Mountain magazine. For the first time ever, there was an overview and a degree of critical analysis about what was happening in Yorkshire. The result? The next edition was filled with more quibbles than just about any other article in Mountain's history. Was Dave Cook some kind of sloppy journo? Nope. Far from it. It seemed to me that the quibbles were there principally to discredit him, a kind of, "We'll show that th' bugger don't know what he's talkin' about." For instance, one of Cook's many alleged sins was to mention a new route called 'The Chopper' when apparently the correct (changed?) name was 'Hatchet Crack'. Pause for hollow laughter…

"Well, if you saw the guy [Pete Livesey] climbing, he was a good climber, but there was always some jiggery pokery going on. He didn't need to. He was good enough."

But the laughter was destined to stop. Cook had made a tantalising reference to 'itchy fingered upstarts' waiting in the wings and a prediction that limestone was going to be transformed. He was spot on. Pete Livesey emerged as the most lethally determined upstart. Pete had been a top runner, coming cruelly close to a four-minute mile in the late 1950s. He'd been a top caver. He'd been a top canoer. Yet in every case, he'd lacked natural talent and thereby not been the absolute best. Pete looked at climbing and saw an athletic curve that hadn't taken off. He didn't need natural talent to be the best.

"Nowadays we make up a lot of rules, put them into a strait jacket, and call them climbs."

The result was predictable. Almost immediately, the YMC tried to discredit him. His routes seemed destined to be ignored. But Pete fought back. A few years previously, the then Ed Ward-Drummond had self-published a self-serving guidebook, 'Extremely Severe in the Avon Gorge'. Pete did likewise, with a slim volume entitled 'Lime Climbs'. It came with a warning that many of the routes were recent and hadn't seen many repeats. People should be careful.

Routes such as the FA of Jenny Wren (E5) at Gordale and the FFA of Central Wall (E4) at Kilnsey, formerly an old Austin aid route, served clear warning on the YMC that Pete wasn't going away. In the Lakes, Austin's other fiefdom, Pete was equally active – as were others. Here the Fell and Rock Climbing Club (FRCC) decided whose routes went into guidebooks – and whose didn't.

"I do not see crags as impressive backcloths where ruthless men can construct their climbs."

Austin and Rod Valentine, the guidebook writers, took particular exception to some routes done by a young Lakeland climber called Rob Matheson, especially White Ghyll's Paladin (E3). The result was a vitriolic exchange of letters in Mountain magazine. Austin came out with one of the best lines ever – crags as impressive backcloths.

Well! What can we say? Looking back 50 years later and knowing what happened in the 1970s, Austin was making a valid point. However he was probably making it to the wrong person. Rob Matheson was certainly pushing the boundaries of what was possible in the Lakes. If you push boundaries, especially ground-up, you're probably going to make the odd error, here and there. But Rob Matheson didn't seem ruthless – whereas other people most definitely were.

"I could number all the best climbers in Britain on two hands. They wouldn't be these gymnasts."

The exchange was painful. Yes, Austin had a valid point. But he nevertheless came across as somewhat priggish. Everybody I knew had immense sympathy for Rob Matheson. And when Rod Valentine did the first ascent of The Cumbrian (E5) on Esk Buttress, with several points of aid, it looked unpleasantly like hypocrisy – one rule for FRCC members and another one for everyone else.

As Austin readily acknowledged, he'd made errors also. But let's take a revisionist look at the two routes of which he was most proud. The aid on Nightshade would probably have kept it out of a FRCC guidebook. With Wall of Horrors, apparently there was an awful lot of top rope practice and (allegedly) combined tactics on the boulder problem start. So should Austin be disqualified from both ascents? I would argue certainly not. But I'm not a guidebook writer.

"Everybody makes mistakes, and I think I have fewer pitons per foot climbed of any climber of my own time."

In 1974 I bumped into Austin in Shipley Glen and spent a pleasant afternoon bouldering with him. He couldn't have been better company. He was bland, affable. Not at all what I was expecting. He came across as a nice guy.

Shortly afterwards, Pete Livesey did the first ascent of Right Wall (E5), the hardest route in Wales, along with the first ascent of Footless Crow (E5), the hardest route in the Lakes. He'd demonstrated clear supremacy over his rivals. He couldn't be conveniently dismissed as some kind of 'anorexic weirdo'. Put bluntly, he'd won. The YMC and the FRCC suddenly looked like the past – not the future.

(But please note. We're going back 50 years. This is a personal point of view, from an outsider. And without the YMC and the FRCC, there wouldn't have been comprehensive guidebooks at all for Yorkshire and most of the Lakes. Also, as enough guidebook writers have assured me, it's very hard – and often thankless – work. So things need to be viewed in context.)

"He [Austin] had very clear views on climbing 'ethics'. I particularly remember him telling me that there was effectively no difference between a peg for protection and a peg for aid." (John Stainforth)

Around this time, two other things happened. Austin, previously 'the absolute amateur', in the words of Dennis Gray, became involved with his brother David's climbing shop in Bradford. Fair enough. The wool trade was in decline; it was probably a sound career move. Coincidentally, despite saying, "I think I will always climb," he gave it up for sailing. Again, fair enough. If he was no longer enjoying climbing – or yearned for another activity – then why not? He left a tremendous legacy of routes. He'd made major contributions to Yorkshire and Lakes climbing and done fine routes in Scotland and Ireland.

"People look at them and your reputation is limited to one or two climbs. How many routes do you think I did on grit? I did 400 new ones, plus 200 on limestone and 100 on what you'd call volcanic rock."

Early in the 2000s, one evening we were messing around at Pex Hill when a cheerful rogue turned up who claimed he'd known Austin since 1959. He regaled us with stories of a Yorkshire where black was black, white was white and there was precious little in-between. It bred stalwarts such as Geoff Boycott and Fred Trueman.

I remember one tale when apparently a bunch of mates had arrived one evening, unannounced. Mrs Austin pointed grimly. "He's in the cellar - working!" Trooping down the steps, they discovered Austin slumped in an armchair. With one hand he was banging away pointlessly at a lump of metal; the other hand held a guidebook which he was avidly reading.

"I can still picture the moves on these routes. It's amazing, isn't it? I haven't climbed for fifty years."

So often our climbing heroes remain, well… heroes. It's hard to imagine them in real life. Standing in line at the supermarket checkout? Struggling with tax returns? Such prosaic images can be difficult to reconcile with our romantic notions of them.

Regarding the climbing shop in Bradford, his daughter Sue charmingly notes that Austin was a somewhat reluctant retailer. (Similarly, did anybody ever see Joe Brown in his shop? I think not). Brown and Austin almost certainly had fierce work ethics, could face horrendous run-outs on rock but probably quailed at the thought of facing a customer. (Ironically, the wily Whillans, also no stranger to horrendous run-outs, but with a negligible work ethic, could probably have flogged yellow flavoured snow to the Inuit – if he'd been even half bothered). Sue recalls a concerned Saturday staff member alerting David Austin to the unwonted presence of a scruffy character lurking in the back of the shop. On closer inspection, it proved to be none other than… well, you can guess.

***

So what on earth are we to make of Austin? For almost 20 years he climbed ferociously. Then, while only in his early forties, he packed it in for almost another 50 years. He developed an 'Austinian fervour' which now seems quirky, quaint, occasionally uneven. And yet one senses that his heart was always in the right place.

Was he a good egg? Yes, I'm certain he was. A trifle hard-boiled perhaps. But, when all's said and done, a damned good egg. And forever a Yorkshireman.

***

Notes

All quotations are from Allan Austin, unless otherwise stipulated.

My grateful thanks to the following, who have helped with photographs and/or reading various versions of the text: Sue Austin, Brian Evans, Michèle Ireland, Phil Kelly, Bob Parker, Iain Peters, David Price, Angela Soper, Jack Soper and John Stainforth. My apologies to anyone whom I've inadvertently omitted.

I take sole responsibility for all opinions expressed – and any errors there may be.

With the passage of so much time, it's been impossible to find out much about some of the original photographers and solicit their permission to use their work. The sequence on Wall of Horrors (and some of the other shots?) were from a talented photographer called Roger Pearson who lived in the Leeds-Bradford area.

The Austin quotes have been shamelessly 'borrowed' from two excellent interviews which are well worth reading.

One is with Robin Nicholson in Yorkshire Gritstone, Volume 1. It's reproduced here: https://climbing-history.org/climber/1213/allan-austin

The other, with Dennis Gray, is in the Leeds University Union Climbing Club Journal, 1973. It's reproduced here: https://footlesscrow.blogspot.com/2020/11/allan-austin-interview.html

I seem to remember that there was also a short article, by Frank Wilkinson, I think, about Allan Austin in a late 1970s edition of Crags magazine.

Denis Rankin, my climbing partner in Ireland in the late 1960s, once mentioned an article, written by Brian Evans, about the Poisoned Glen routes. I believe it was in Climber and Hillwalker, but I don't think I ever managed to find it.

However, for someone who did so much, there has been surprisingly little written about Allan Austin – probably the way he'd have wanted it.

More Articles

Comments

Thanks, Mick, that was a good read. When I started caving 'properly' in the seventies we used to meet up at Brian Evans's house near Preston. I recall once while we were having a brew, he brought out some photo albums to show us. All black and white shots of Allan Austin (plus a few other aspiring hopefuls like one Joe Brown!). I'd done a bit of bimbling around the local quarries to know my history and that those pictures were pure climbing gold. A few years later when I got more into my climbing I think of all the figures I could most relate to it was Allan Austin. It was for his limestone routes more than grit as this was what was easier to reach and we saw those crags often when we were out caving.

Good article, nicely written and a pleasure to read.

Re: "ground up". If my memory serves me right Austin's point was that they were not, and that routes should be doable ground up. Pretty sure Cruel Sister and another, Pecadillo, were first done by abseiling down and preplacing slings for aid.

I think that was the argument, oh and that the easiest line should take precedence on a new piece of rock, not the 'eliminate'. Paladin, a blindingly obvious line that others had left for someone who was good enough. Why Matheson put a peg in it i have no idea, perhaps it was loose. It's a zillion grades easier than say Holocaust on Dow so should have been a stroll. Whether or not there was an ulterior motive to these arguments, i wouldn't know. To be slightly provocative, you could argue that Austin was right when you see really truly amazing vids of Matheson repeating these routes free in his '70s that he used aid on in his twenties. I only mention it because i had some sympathy for Austin's views. It doesn't matter in the slightest of course.

A right good read about a fascinating character.

l I recall these arguments getting played out over several months in the letters page of the climbing magazines. Sally free and easy v Ragman’s Trumpet was another spat . However if I recall correctly the frcc were being a bit hypocritical over the use of aid and it all seemed a bit like dogs fighting over territory.There is no doubt though that Austin was an absolutely amazing driven climber whose contribution to climbing was irreplaceable.

Excellent article. Thanks