Glacial Travel: Part Two - Rescuing a Fallen Climber

In conjunction with the 2016 Arc'teryx Alpine Academy in Chamonix, France, we have a series of articles on some key skills in Alpine climbing. In this second article, Chamonix-based skier and alpinist Dave Searle shares his advice for rescuing a fallen climber.

In this second and final part of my article series about how to move safely on a glacier, we look at how to hold somebody who has fallen into a crevasse and some of the basic methods for getting yourself or someone else out of a crevasse. In the first part (Glacial Travel: Part One) we covered the basics of glacier travel, and how to rope up. So I hope you've read and understood that article first!

As a starting point let's assume that both team members have tied on to an end of the rope, taken coils (or even stashed the spare rope in your bag) and tied them off in the correct way so there is approximately 15m of rope between them without knots on that rope. Although knots make it easier to hold a fall it also makes it a lot harder to perform a rescue so until you practise hauling someone out with these knots in place I recommend not putting them in. Each member has a French prusik on the rope already and they are both wearing crampons and carrying an appropriate ice axe for glacial travel. They also have the correct equipment outlined in the previous article to perform a hoist rescue.

The first and probably most difficult part is holding the fall in the first place. This requires practice and there is nothing better than a good old fashioned game of tug of war to give you some idea of what it really takes to hold someone. Give one person a few metres of slack on a flat bit of glacier and let them sprint away from you. Now try and stop them…You'll probably find it best if you get down low and dig your crampons and axe into the snow. Next see if you can stop yourself and a friend sliding down a slope. Make up some other scenarios in a safe controlled way to prepare your mind for what you need to do when the proverbial hits the fan.

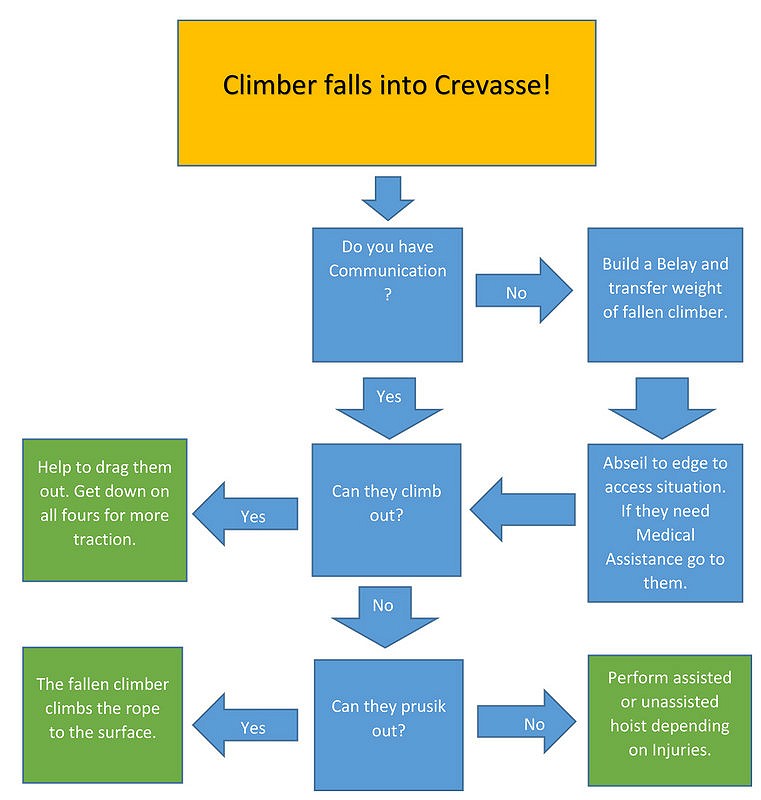

Now let's imagine a few scenarios starting with the simplest first working up to some more complex situations and talk a little bit about what to do in each one. But first up here's a handy flow chart (because everyone loves a flow chart) on the process of crevasse rescue.

A climber falls in but is uninjured and close to the surface. In this situation the simplest and quickest way to solve this problem is for the other climber to get down on all fours and start climbing away from the stuck climber as the one who has fallen in pulls him or herself out. Quite a common one and is likely to happen during a summer of alpine climbing. Make sure you shout if you feel yourself start to fall in!

A climber falls in completely but is uninjured and you have communication. In this case assuming you have held the fall and they are hanging off your waist you would build an appropriate belay (Buried axe or ice screw, the explanation of both is beyond the scope of this article) and get the climber to prusik out of the crevasse so the rope does not cut further into the snow. This is the easiest way to get somebody out if they are capable of prusiking up a rope. Here's a lesson on how to do it from Steve Long showing the use of two ropemen in lieu of two prusik loops. If you have a long way to climb up then it is worth backing up the prusiks with a clove hitch on your harness.

The next scenario is that when a climber falls in you lose all communication with them. Either because they are too far away or they are unconscious. In this situation you need to assess the situation by getting a visual on them. The best way to do this is to abseil to the edge of the crevasse. Build an anchor and head down towards them. If they are unconscious, you need to stabilise them immediately by going down to them and performing First Aid and making sure their body is supported by a chest harness. If it is possible, bring the climber to the surface using an unassisted hoist. You can see an unassisted hoist in this video below by La Chamoniarde.

The last scenario is that somebody falls into a crevasse and you have communication with them but they have sustained some injuries for example a Broken leg. They can still use their arms. In this situation you would build a belay and perform an assisted hoist. This is virtually the same as an unassisted hoist except the loop of rope which goes to the sliding prusik goes down to the belay loop of the climber who has fallen and is clipped on with a screw gate, preferable with a pulley on it. They then pull down on the appropriate side to assist you bringing them up.

There are hundreds of scenarios and many ways to deal with them. I hope the advice given above is a good foundation but it is in no way exhaustive. It is always best to seek advice from a mountain professional if you don't know what you are doing, however, if you do venture out onto a glacier remember these key points:

- It is very important to get communication with the person who has fallen in. If you don't have it then build a belay immediately and assess their situation by getting closer to the edge and if need be go to them and perform First Aid.

- Your belays should be boom-proof. If you don't know how to build an appropriate snow anchor, then you should not be on a wet glacier unless you are with a Mountain Guide. Learn how to build them and what their limitations are.

- The person who has fallen in should take the responsibility of getting themselves out unless they are injured. Be proactive. It's very difficult to perform an unassisted hoist so it is to be avoided at all costs. Practise prussiking and hoists in safe, controlled situations. Get some advice or go on a course if you need to.

- You both need spare rope and the appropriate equipment to perform a rescue. Without the gear you won't stand a chance of getting someone out.

Glaciers are dynamic, ever-changing environments which require care and thought to travel through safely. Try not to let your guard down just because there is a track in or some other folk about or you're boiling your brains out slogging back to the lift station. Having said this don't be afraid to ask for help if you can! It will make things a lot safer having more equipment and man power.

There you have it. I hope you've gleaned something from this article series. It has been tricky to write in some ways but has given me the chance to reflect on the systems we use and to gain more knowledge myself. Safe travels out there everyone!

Visit Dave's Blog.