Chalk Use

It is slightly ironic that an article such as this should be written by someone that, until a few years ago, would never have considered themselves a boulderer. However, coming from a trad/mountaineering background has provided a deep understanding of an ethic that should stand true amongst all disciplines of 'the sport': leave it as you found it. In fact, these days I'd go a little further - leave things better than you find it: pick up litter, brush off those tick marks, and have a general tidy-up before you leave.

The main focus of this article concerns one of the more visual aspects of bouldering - the excessive use of chalk and tick marking. Back in the 1970s the 'Clean Hand Gang' were a group of activists who eschewed the use of chalk, as they said it ruined the rock and diminished the adventure (as you can always see where the holds are, thus it makes it a lot easier). I'd always thought they were crackpots to be honest, and at least where trad routes are concerned, had never viewed chalk as a negative - in fact I think that chalk on a route can make it more beautiful as you can see the lines and some of the otherwise more subtle features. Chalk can give a route some context and meaning.

On boulder problems, due to their naturally shorter nature, this is something that is very much condensed: fewer holds and more goes/attempts often leads to more chalk; there tends to be greater build up, thus it becomes more noticeable.

So, what's the problem?

Cosmetic - it's very, very ugly…

Whilst a little chalk could be considered beautiful to a climber, a lot of chalk is beautiful to no one. This has an impact with other outdoor users: hillwalkers, environmentalists who may well see this graffiti and see it as detracting from the natural world they have come to see.

Overuse can also lead to staining the rock, where the chalk essentially bleaches the area around it, leading to the rock becoming a paler colour. If there's a great excess of chalk left on the holds, this can also lead to the horrid drips and tears of chalk leading down from the holds. For anyone suggesting that excess chalk is magically removed by rain, it is not - this is the consequence.

David Mason - climber, coach and advocate of best practice

Friction - more is less, less is more…

Friction varies from rock type to rock type and there's little that chalk can do to improve or worsen the frictionless nature of either slate or polished limestone. For more friction-based rock types, such as gritstone and sandstone, grip is often gained by the rough nature of the rock's exterior or the pores within the rock itself. If there is one swift way in which to reduce the rock's natural grippiness, it is to lather it in chalk, which will clog the pores and reduce the friction (this applies to both hand and footholds). Patting a chalkball against the rock repeatedly is also a big no-no.

Remember, less is more!

Tick marks - fine in moderation, providing they're brushed off afterwards

There is no harm in the occasional dot or dash here and there, providing they are brushed off afterwards. However, having just got back from a week in Fontainebleau where I saw countless 'in-situ' tick marks, I think this message needs to be shouted even louder. Perhaps just have a quiet word with yourself beforehand: does the hold need actually need ticking? In some cases I've seen jugs and ledges ticked, even though you'd have to be blind to miss them. As such, maybe refrain from ticking everything and just focus in on those more subtle, hard to hit holds that require a little guidance to hit properly.

Another issue that comes alongside the tick mark is the 'donkey mark', which is a phrase I love, as it adequately summarises the inelegance of the longer tick-marks that seem to have arisen in recent years. Rather than paint these over the rock, it could be worth considering either using a smaller tick-mark, asking a friend to point at the hold in question, or just trying a different problem!

1. Tick marks aren't evil, but try to keep them small and discreet

2. Try using a small dab rather than dragging the rough edge of a piece of block chalk, the former rubs off a lot easier

3. Once you're done, give it a quick clean in order to return the problem to its natural state

Matt Wilder - Tick Mark Master from Access Fund on Vimeo.

Mina Leslie-Wujastyk - professional climber

Chalk is for hands, not for holds

Another common misconception relates to chalk's ability to dry holds. If a hold is wet you have two options: firstly, and perhaps most sensibly, climb a different problem. This is particualrly important for porous rock types such as sandstone, where climbing on them in their wet state could lead to irreparable damage as holds are far more susceptible to breaking whilst damp. Secondly, if appropriate - as it is on certain rock types such as limestone - you can try drying the hold in question with a towel. Don't (whatever you do) try to smother/smear the problem back to health with a paint roller of chalk or pad a chalk ball repeatedly against every foothold. If in doubt, walk away...

The picture below is a good illustration of the above and was taken by Steve Riley, his comments - rather confusingly - were "those footholds are big, dry and easy to spot, the one on the left possibly the biggest foothold on the crag. Stuff at hip height mostly ornamental in the wrong place. Rubbish pic but there's a liberal coating of dandruff between. Sigh...". Why the need for the chalk - is it just for decoration? What was the reasoning or thought process behind it? Therein lies the crux of the matter: is this just a case of misguided behaviour; a lack of understanding of the etiquette. The answer is simply that I really don't know or understand.

Dan Varian's Commandments of Chalk Use

If you think in those terms and come across a problem covered in chalk, it's not supposed to look like that. If you think you can fix that, then do.

2. Not all brushes and rock types are equal

The flip side of using chalk is that it needs brushed off. Here is where other problems can start as depending on the rock type that can lead to it eroding or polishing over time if lots of people brush the same holds in the same ways. for sandstone/gritstone brushes and dirty feet can spell disaster. This is a tricky situation for even the most experienced climber to know whether brushing a chalky hold or leaving it is the right thing and each case is an individual one based on the popularity of the area you're in and the hardness of the rock you're on. If you are in doubt I'd say don't brush the hold, especially if it isn't completely caked in chalk.

3. Excessive chalk use on handholds doesn't increase the friction

Whacking chalk all over holds doesn't always increase friction. This is again a tricky case of friction and chalk not always working together. Some rock types work much better with no chalk on them at all, rough ones like gritstone are good examples of this; clean holds with no chalk are the grippiest holds you will find. After a few tries and the day's chalk getting bedded in, the initial bite can go. For very glassy rock types a dusting of chalk on the hold can help. If any physicists want to inform us as to exactly why, I'd love to hear it. Generally I would guess that the chalk crushing between the skin and the rock melds the two surfaces a little more than a smooth unchalked surface? A dusting is all you need as more than this and the chalk seems to slide over itself and next thing you know you're taking airlift to the ground floor. The only thing that chalking footholds does is make them easier to see.

4. Brushing off your chalk after climbing is a mark of respect to other climbers; it's just a nice thing to do. You might forget from time to time, everyone does, especially if you have to rush off - but that doesn't excuse it entirely.

Just be nice and make up for it another time by cleaning a problem when you find it. Chalk also kills a lot of lichen species. This is why you see big clean streaks on popular problems, which can be unsightly on some rock types - another good reason to leave the rock as clean as possible.

You wouldn't leave a turd in the loo for your mates and expect them to thank you for it. Problems caked in chalk are a similar calibre of gift to climbers.

It's nice to be nice. Brush 'em and flush 'em kids. Brush 'em and Flush 'em.

#respecttherock on the UKC Galleries and Twitter

Conscious that best practice takes far more than just a single article, UKC have teamed up with Black Diamond and the BMC to continue the theme of the campaign both on site and on social media using #respecttherock.

Upload your pictures before and after, tell your stories, and together - with any luck - we can encourage people to treat the rock and the environment with the respect they deserve.

Each month we'll be doing a giveaway to the best (or should we say worst) photos, with prizes from Black Diamond and Rockfax.

Photo Gallery

A sorry looking Gorilla Warfare

© David Mason

Jan 2019 access restriction sign in Albarracin car parks

© Michael Bortoluzzi

Grit is a precious stone. Chip Shop Brawl.

© Ian Carr

Grit is a precious stone - Low Rider Stanage End.

The biggest chalk dab is about 30cm diameter

© Ian Carr

Multiple holds cemented by a moron

© nickcanute

Belay bolt above The Sun, Llawder, Rhoscolyn (chopped June 2019)

© Si Witcher

Problem with chipping? (2)

© uphillnow

Problem with chipping?

© uphillnow

Some of the rubbish collected from the 2018 Chee Tor Revival

© Rob Greenwood - UKClimbing

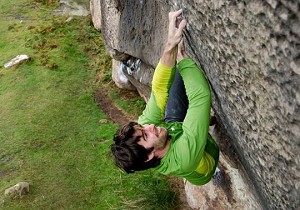

Ricky approaching the crux

© Michael James Spring

Attack of the flaming marshmallows - stinging nettle, stone farm

© RobertHepburn

Chipped and brushed

© mark s

About the Author:

Despite once proclaiming Scottish Winter climbing to be the 'one true faith', Rob now prefers to spend his winters bouldering on the Gritstone of both Yorkshire and the Peak District. Some say he's gone soft, others say he's got wise - we'll let you be the judge. When he's not climbing the chances are that he's thinking about climbing, reading a (climbing) guidebook, or volunteering for the BMC.

He keeps a (very) occasional blog and - when allowed out the office - even writes the occasional article for us too.