Toby Dunn writes about his Desert Island Climbs and reminisces not only about the climbing itself but those he shared it with and the experiences he had along the way.

What follows is an entirely subjective list, not based on any objective notion of quality but only my experiences or feelings about the routes.

Aviation (E1 5b) (E1 5b), Haytor, Devon

I started climbing where I grew up, in South Devon, with a schoolmate who had got a rope as a present and aspired to be a mountaineer. He used to drag me out climbing when I really wanted to continue indulging my teenage obsession for windsurfing. I often seconded pitches that he had led, sometimes under duress and often did not really enjoy the experience. However much I had to endure them, I noticed that the experiences became addictive. I began to read guidebooks, obsess about routes and tried to find training traverses on the limestone block walls near my home.

The first time that we climbed Aviation, we shared it as a two-pitch route. I lead the first; an awkward crack on the painfully rough Dartmoor granite, followed by a rightward traverse on enormous quartz crystals to reach the belay on a pancake of rock adhering to the spiky slab. I gratefully seconded the second, as at the time I was still terrified of heights and hated anything taller than a highball boulder problem. In reality, it is a glorious rounded runnel cut into the iron-hard granite to reach a bold, though extremely low angle slab. We chatted enthusiastically about the route while sitting on the summit, trying to sort out the tangled mess of our single 11mm rope. For me, Aviation symbolises the moment when I really started to love climbing, rather than doing it because I liked the idea of it.

Heaven Crack (VD) (VD), Stanage Edge

I can't remember when I first climbed Heaven Crack or the most recent time, but it is everything I love about gritstone. A lovely layback flake and a series of rounded breaks comfortably carry you to the rim of the gorgeous crenellated edge which runs for five miles or so from North to South, its face looking out across Derbyshire, its back a gently undulating heathery hillside sliding down into Sheffield. I've been climbing for nearly a quarter of a century, which is a terrifying thought, and I very seriously considered packing it in a number of times, for a number of different reasons but Heaven Crack will always remind me what I love so much about it; I find it impossible not to smile every time I climb this route.

Darkinbad the Brightdayler (E5 6a) (E5 6a), Pentire Point, Cornwall

Several of these routes are really about the shared experience. Darkinbad is a great experience to share with any friend who can lead one of the pitches. Pentire Head, if you haven't been there, is a sort of coastal Cloggy. It sees very little sunlight, the rock is dark, foreboding and the routes intimidating and bold. I've always enjoyed the close juxtaposition of the comfortable and mundane with a gothic menace that characterises some of the best of UK sea cliff climbing. Well-groomed grassy footpaths, National Trust properties and ice cream shops only steps away from staring down a miserable sloping crimp two hundred feet above a jagged bouldery beach, strewn with the tendrils of fragrant seaweed and wheeling seabirds mocking your pedestrian vertical progress. The cool, bold and physical experience of Darkinbad is satisfyingly sustained for virtually its entire length. No grassy rambly pitches break its moody intensity. The relief of sitting on the soft heathery hillside above chatting about what a fantastic route it was, and how they had better route names in the '70s is short-lived as you start to feel the pull of the darker, murkier world beneath and perhaps a dose of Black Magic (another incredibly good E5 at Pentire).

Souls (E6 6b) (E6 6b), Huntsman's Leap, Pembroke

The west wall of the Leap is one of my favourite pieces of rock on the planet. It has a scalloped, cool smooth character. The route names are rather reminiscent of a Victorian horror novel. 'Darkness at Noon', 'Minotaur', 'Headhunter', 'Witch Hunt'.

Souls: 1. The spiritual or immaterial part of a human being or animal, regarded as immortal. 2. Emotional or intellectual energy or intensity, especially as revealed in a work of art or an artistic performance.

I certainly don't think that me fighting my way up Souls was in any way artistic, probably more of a struggle than a performance. However, Souls encapsulates everything that I love about British traditional climbing. It is alternately very bold and reasonably hard, but not at the same time. I have never aspired to the boldness of routes like The Bells, The Bells! (E7 6b) or The End of the Affair (E8 6c) where the hardest climbing is very poorly, or not at all protected. Souls is very bold on easier, but still challenging ground, and extremely well protected where it counts. It saves the hardest moves until the end, as many of the best routes do. It has real atmosphere and like anything that challenges you in the Leap, you feel lonely and adventurous casting up off the sandy floor of its tidal trench; you're absorbed for the entire of the considerable length of the pitch and crawl your way with relief and joy onto the grassy cornice that caps it, only to realise that there's a small audience watching you with interest, or possibly horror, a short distance away on the top of the other side.

The Cow (E5 6a) (E5 6a), Yellow Wall, Gogarth

Yellow Wall is sunny and inviting; the sea sparkles in the sunlight as it laps quietly around the boulders at the base. A stone's throw away from the seacliff-lite experience that is Castel Helen as soon as you abseil in, Yellow wall shows you the real colour of its character. You're hanging in space, it's miles down to an uncomfortable rubbly slope, a more uncomfortable distance above those boulders and the sea, all of which look decidedly less appealing and pretty now you're down there. A crowd of dozens of noisy little birds mill around beneath you as if trying to distract you from the task of how to secure yourself to this uncertain slice of Holy Island as safely as you can. Break lines in the strata twist out across the steep wall. It's hard to work out how steep it is as there's nothing level to compare it to down here. Both pitches of the Cow feel quite steep enough, and the rock quality is what qualifies for really good in the context of routes at South Stack in general.

The midway belay is outstanding, I'm a real fan of an exposed belay ledge, and this is a real star of a place to have a nice sit-down. Perhaps my abiding memory of The Cow is chatting to an American birdwatcher whilst we coiled our ropes on top, who told me that she'd been there a week looking for choughs but hadn't seen a single one yet. I momentarily wondered about offering our abseil rope to her, as I realised that the mildly irritating little critters populating the bottom of Yellow Wall were choughs. It is all too easy to take for granted the amazing things that you just happen to see if you spend time climbing, from peregrine falcons dive-bombing pigeons to feed their chicks at their nest at Malham Cove, to seals and basking sharks sunning themselves underneath sea cliffs, to water voles emerging from their riverside burrows at the base of Peak sport crags.

Colosseum (8a), Rodellar

It is all very well harping on about how much you like moves, lines, form, rock quality or aspect, but when you get a really good one, perhaps the best thing about sport climbing is the swing. Colosseum does have a great line, it follows a very open groove line straight through the centre of the Gran Boveda for nearly forty metres. It does have really good moves, satisfying kneebars, cool holds but the really special thing is lowering off after a successful ascent and removing the lowest quickdraw. The ground below slopes steeply down towards the river, and as soon as you yank the upper krab of that quickdraw out of the bolt hanger, you accelerate backwards at a terrifying pace. It seems to go on so long, you feel as though you are going to end up arcing across the Iberian peninsula and landing somewhere near Tangier.

Onde de Choc (f7B) (Font 7B), Apremont, Fontainebleau

I haven't been for years now, but every time I go to Fontainebleau, with virtually any problem I have climbed there of any level, I am filled with the powerful feeling that I could happily climb nowhere else for the rest of my life. It is, in so many ways, the perfect place to rock climb and every problem schools you in how to combine precision, strength and often boldness. The only thing that Fontainebleau lacks for me is a real view. Onde de Choc is a physical, overhanging prow with a series of the sort of perfectly formed holds that makes climbing there at any level such a constant joy. It rises just high enough above a good sandy landing area to give it some interest but not enough to tip it into the realm of worrying more about the drop than the next move.

Lord of the Thais (Multipitch) (7b) (7b), Railay, Thailand

It's about six o'clock in the morning and we're all wandering across the beach at Railay barefoot, carrying our flip flops; no one else is out yet, not even the Swedish package holiday groups who seem to have the constitutions of oxen, showing an impressive ability to lie in the South East Asian heat all day drinking huge beaded tankards of Thai lager with unpredictable alcohol content. The Thaiwand wall is on the far side of Railay and overlooks the bay, its face fringed with a rich profusion of palm trees.

No two of us wandering out to climb Lord of the Thais are from the same country; this is one of the things that I really love about climbing: its ability to put you in places that you otherwise would not be in, or to see them with different eyes to someone who is travelling for the sake of it. I do not mean to denigrate 'travel', it is a fantastic, potentially enriching experience of which I have done plenty myself. However, if I hadn't gone to Tonsai on my own with no climbing partner, knowing no one, I would never have met any of these people, heard their stories about home or shared day after day of trying to climb tufa-dribbled crags in the tropical heat with them.

Lord of the Thais is, in the context of the vast majority of the climbing in the bay, a real adventure. It is roughly five or six pitches, the harder ones are high on the route and extremely overhanging. The highlight pitch is a fantasy of chunky tufa blobs sprayed across the bulbously steep wall. After a steep abseil down, the Australian - Vietnamese pair of our little expedition strolled off in the direction of Tonsai to go and telephone their families for a chat. The Swedish - British pair found a shack to feast on Pad Thai and Som Tam and to chat enthusiastically about which crag to go to in the afternoon. We felt as though we should probably try to make the most of Christmas Day.

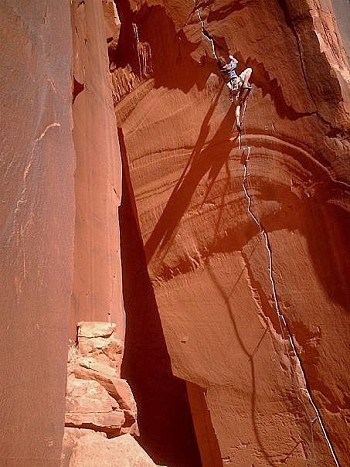

The Rostrum with the Alien Roof (5.12a), Yosemite

I've climbed The Rostrum a couple of times and of all the Yosemite longer free routes I've done, it is perhaps the most enjoyable. Much though I absolutely love Yosemite, doing many of the routes there is a long, hard day out with the prospect of a complicated descent afterwards. Many of the decents demand concentration, route finding and the ability to move reasonably quickly unless you like being benighted on small ledges. The Rostrum gets a comparatively straightforward abseil out of the way straight away, as you approach from above, and the top is a short stroll along immaculate granite slabs and scrubby pine forest back to your car.

The cracks on the Rostrum have a positive, reassuring character unlike the gleaming rounded brutality of much of the climbing in the valley. At about eight pitches, it is long enough to feel like a reasonable route, but not enough to become arduous or stressful. Writing that the Alien roof is neither arduous nor stressful feels rather deceptive, with it being a horizontal roof crack a clear thousand feet above the ground, but feeling very small on the belay ledge below the pitch, I remembered the words of a good friend who said that he wasn't worried about heights on the many big walls that he'd soloed since 'after a pitch or two trees look quite small, and after thirty or so, they still look quite small.' I'm not sure I've ever reached that state of blissful ease with verticality, but it was a good comfort blanket. However vigorous the butterflies in your stomach, however, I'd argue that it is impossible not to enjoy a route which leaves you at the lip of a huge roof, absolutely miles up in the air with two unimpeachably good fingerlocks in the crack of the merely overhanging wall above, feeling like a hero for a brief second or two, before remembering how pumped you're starting to get. The Alien is everything I always thought Separate Reality would be when I used to pore over climbing magazines and marvel at the pictures of Wolfgang Gullich soloing it, in awe.

The Optimator (5.13a), Indian Creek, Utah

- ARTICLE: Feeding the Rat - A Climber's Life on the Edge of Edibility 28 Apr, 2021

- ARTICLE: Room 101 - Toby Dunn's Worst Climbing Experiences 9 Feb, 2021

- ARTICLE: Close to Home - Climbing & Travel in a Post-Pandemic World 9 Oct, 2020

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Gorges de l'Aveyron 1 Feb, 2019

- ARTICLE: Helmets - Keeping a Lid on it? 31 May, 2017

- ARTICLE: Like I need a Hole in the Head 8 May, 2017

Comments

Enjoyed that.

Gave me a good balance of 'I remember that', 'I want to do that' and 'I haven't heard of that, but it sounds cool'.

Thanks Andy. I hope you get a chance to do the ones you want to do soon!

Great artical. I think that route in Indian Creek in the photo is Annunakki.

Really enjoyed that. Very well written.

Great stuff Toby! Have done a few and would like to do the others!