Part 1 - Training in Sync with your Hormone Cycle

In this series, I hope to provide a systematic approach for climbers to syncing training with the menstrual cycle. With the increase in discussion surrounding hormones and the changes to our physiology during the menstrual cycle, it is easy to get overwhelmed. Before we dive into everything "periods, hormones, and cycles", first of all we need to think about the best approach for us. We can view our climbing and training as a pyramid; without a wide base, the whole thing would topple over. We need to start from the bottom, which means starting by laying strong foundations.

There are many reasons why climbers start training; to reduce injury risk, to make strength or endurance gains, to be time-efficient when juggling a busy job or parenthood, to account for shifts in life stage (menopause/post-partum), as well as for the simple enjoyment of it. If these goals are affected by hormonal changes during our monthly cycles, then it seems worth knowing how best to adjust our training to optimise our health, performance, and experience.

Each part of this series will by no means provide the whole picture, nor cover the full range of individual experience, but I hope that we can start to build a base that can help climbers increase their body literacy when it comes to the menstrual cycle.

Introduction

The menstrual cycle is an extremely important biological cycle, yet for the majority of my reproductive life the conversation around periods, the menstrual cycle, and contraceptives has been pretty quiet and somewhat taboo. However, in recent years it has been getting louder, with research, sports news, podcasts, and apps focusing on female physiology with the aim of optimising health and sports performance. Outside of this, there is the broader issue of the dropout rate from physical activity and recreation in the outdoors during the different reproductive stages of life, which has an impact on both physical and mental health. Education surrounding the hormonal changes throughout the monthly cycle, as well as different stages of life, will hopefully allow climbers to adapt rather than drop out of climbing and training.

However, with the menstrual cycle becoming a hot topic, we can find ourselves swimming in a sea of information. What applies to us? How does this translate to climbing? Do we need to be at a certain level before considering how our cycle might be affecting our climbing? When the answer to most of these questions seems to start with "Well, it's really individual…", how do we decipher what we, as individuals, need?

The question of a certain climbing level being needed for any intervention is one that is applied ubiquitously. Do I need to climb a certain grade before training? Before fingerboarding? Before falling on gear? The list goes on and there is generally a lot of debate as to the correct answer. When it comes to considering the menstrual cycle alongside climbing or training, it comes down to whether the intervention changes a climber's experience in a positive way. The term "experience" here encapsulates enjoyment, mindset, physical performance, health, adaptation and recovery, and I don't think that these elements of climbing that a lot of us seek are reserved for a certain grade or level. So the question is not "Am I "good enough"?" but "Will this improve my experience of climbing or training?", and to find the answer we first need to understand the ways in which our cycles may affect us.

First things first… What happens during the menstrual cycle?

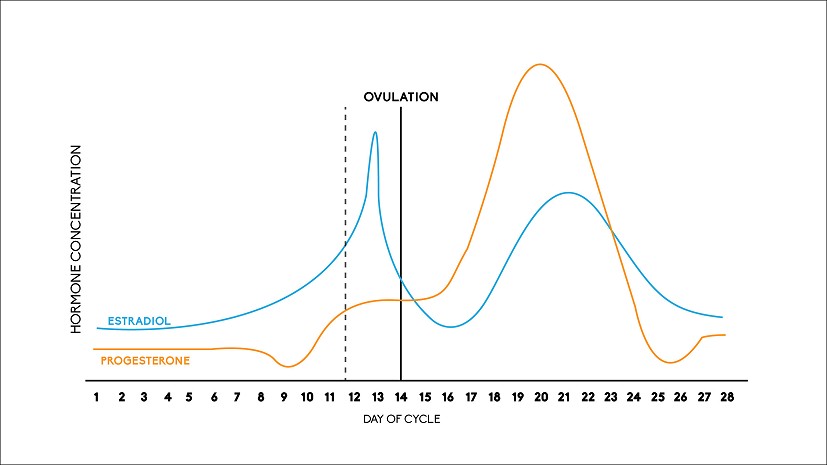

Ella Russell and I put together a YouTube video discussing the different phases of the menstrual cycle. This is a great place to start when it comes to a general understanding of the fluctuation in hormone levels during the cycle and the symptoms that can accompany them.

As much as taking a deep dive into the theory, physiology and endocrinology surrounding the menstrual cycle is interesting, getting to grips with the impact that the menstrual cycle may have on our climbing from a real life perspective is what will make a difference to our experience.

So what are some of the main points to keep in mind?

- Although it looks neat to describe the cycle as 28 days long, with ovulation around day 14, separating the low hormone and high hormone phases, in reality we are not textbooks. This will vary greatly between individuals, but potentially also between cycles for a given individual. Life has a tendency to fluctuate as much as our hormones, and the systems in our bodies are not isolated, therefore, stress (whether that is emotional, physical, or nutritional) will have an impact on our cycle and the symptoms that come with it.

- The low hormone phase (or follicular phase) is considered the phase from day 1 through to ovulation. Remember that day 1 of the menstrual cycle is day 1 of bleeding, so this phase includes menstruation.

- Towards the end of the low hormone phase estrogen rises to stimulate ovulation. This also coincides with a spike in testosterone.

- After ovulation estrogen falls, but then both estrogen and progesterone levels rise for the remainder of the cycle. The phase is termed the high hormone phase (or luteal phase), and the end of this phase is often when the symptoms categorised as PMS are experienced.

- As we can see, the menstrual cycle is not just your period. Hormones levels are changing constantly throughout the cycle, which is why it is common to experience symptoms at times other than during menstruation.

The foundations of structuring our training around the menstrual cycle

When it comes to training, it is worth keeping in mind that picking the low hanging fruit will likely yield the best results. So, when deciding whether we should synchronise our training with our cycle, the first questions we should ask ourselves are:

Is my training periodised to have higher load weeks and deload (or rest) weeks?

In order to adapt to training, it is important to allow recovery periods as it is during these periods that we actually make adaptations. Not allowing frequent rest weeks will impact energy levels and increase injury risk, as well as hamper any response to training. Before we can periodise around the different phases of our cycle, we need to periodise full stop! If the answer to the question posed above is "no", then the first thing to do is record the sessions that you do each week and think about how tiring each one is (you can rate each session on a scale of 1-10 using the Relative Perceived Exertion - or RPE - scale). Another thing to consider is the amount of recovery time needed after a given session. This will depend on the intensity (how difficult) and volume (length) of the session, and can be judged by how tired you feel post-session on the following day. This information allows us to schedule a deload week where we reduce both the volume and intensity of training and climbing to allow for supercompensation (the adaptation to training that leads to a higher performance post-training). The most common pattern used is 3 weeks on 1 week off, however depending on the individual 2 weeks on 1 week off may be preferred to improve recovery. Once we have this structure set up, we can look to overlay this with our monthly cycle to make the most of our training.

Have I tracked my menstrual cycle?

It is important to understand the length, or any variation in length, of our cycles. Our cycle is a marker of our health and changes in length or disruption to our cycles can be an indicator of overtraining, stress, or low energy availability (a mismatch between fuelling and energy expenditure). When our hormone production is affected by stress or low energy availability this can result in early, late, or missed periods. When we use hormonal contraceptives, the exogenous hormones (synthetic hormones not produced in our body) interrupt the natural fluctuation in our endogenous hormones (the hormones made within our bodies). This means that our cycle does not behave like a natural hormone cycle, and any regular bleeding that we experience (for example during the pill-free days on the combined pill) is not classed as a period. This is because the bleeding is caused by withdrawal of the synthetic, exogenous hormones rather than by changes in our natural, endogenous hormones. Some forms of contraception simply stop periods altogether. Although this can be seen as advantageous, it is important to be aware that hormonal contraceptives can mask the red flag of menstrual disruption that is caused by low energy availability. Low energy availability manifests itself in lots of different ways, such as poor adaptation, low mood, frequent injury or illness, reduced memory or concentration, so if this is something you are unsure about, one possible approach could be to have a break from hormonal contraception in order to get a better idea of your hormonal health.

Recording symptoms that impact your training - such as fluctuations in water retention (think bloating!), strength, coordination, motivation, or recovery - over 3-6 months will help to weed out "bad days" (remember not every poor session or tired day will be linked to your hormones!) and get a good picture of what impacts you personally. Despite the interruption to the natural hormone cycle when using hormonal oral contraceptives, we may still experience symptoms around withdrawal bleeds. Furthermore, contraceptives such as the Mirena Coil, that act locally in the uterus, are not thought to interfere with endogenous blood hormone levels in the same way, therefore changes due to hormone fluctuations throughout the month may still be experienced (with or without a discreet period). It is important to remember that there is a lot of variation when it comes to the menstrual cycle, so we cannot be prescriptive when it comes to what symptoms are experienced when, and what impact this may have on climbing. Tracking is about finding the pattern of what affects us as individuals.

If you haven't checked it out already, Ella and I put together a YouTube video discussing tracking.

Training adjustments for health and energy level fluctuations

Once you have tracked your cycle, you will have information that will help you make informed decisions about how to adapt your training. Adaptations to your training can come in many forms; from syncing your deload weeks, to adapting specific training sessions, to being more aware of your nutrition or stress levels. You might even look to introduce more freedom at times of lower motivation and take a step back from structured training or reduce the intensity to help with energy levels. I know this can seem counterintuitive to us keen climbers — surely more is more, and dropping sessions means "failing" at training? The key thing with training is consistency over months and years, so if making some simple changes improves the consistency of your training, then it will likely be beneficial in the long term. Below are a few core changes that can be made with information gathered during tracking.

"My cycle varied significantly in length" or "Through tracking I realised that I am missing periods"

If our energy expenditure exceeds our energy intake, we enter into low energy availability. The energy we take in through our food is required for movement (climbing, training, walking to the shops etc.), but also to fuel life processes such as hormone production. If we don't have sufficient energy available, our bodies will always prioritise movement and it will down-regulate the other life processes in order to do this (you can imagine this was an important evolutionary step, as it was always more beneficial to survival to be able to move to get food or away from danger).

Energy Intake (food) - Energy Expended (movement) = Energy Availability (energy remaining for life processes)

Our menstrual cycle and periods are governed by our hormones, and therefore can be disrupted if our hormone production is down-regulated through low energy availability. Low energy availability is a diagnosis by elimination, so it is always important to seek medical advice if through tracking you find significant irregularity in your cycle. If other reasons are ruled out and you experience more acute shortening or lengthening of your cycle when you start training or throughout your training, then some adjustments to try are;

- Reducing the volume and intensity of training - by completing less sessions in a week you will allow more time for recovery.

- Increasing the frequency of deload weeks - by scheduling deload weeks more frequently, we build up less fatigue.

- Look at your energy intake and especially try to bunch carbohydrates around training - carbohydrates are the main fuel for high intensity training and climbing as well as being important in signalling hormone production, so carbohydrates are a key contributor to the "energy in" part of the energy equation.

- Zoom out and take stock of the other things in your life. Lots of things in life can be "stresses", and it may be that your training and nutrition haven't changed, but you have started a new job and are commuting 20 miles there and back, or you are going through high emotional stress.

It is really important to emphasise that our period is just one piece of the puzzle when it comes to being a healthy climber, and low energy availability can manifest itself in different ways. As always it is individual, and there are numerous examples of athletes that have maintained their period, only to get recurring injuries, illnesses, or stress fractures (this mainly comes from the running community). Therefore, it is important to look at the whole picture when it comes to overtraining or underfueling. The menstrual cycle is just one marker of health and other markers such as fatigue, poor concentration or memory, low mood or motivation, and needing more and more coffees to get going are still as valid as ever!

"My energy levels are lower and it takes me longer to recover during the week before my period."

It is common to feel lower energy in the week before our periods (depending on the individual this may be a few days before and a few days into menstruation i.e. the overlapping period between two cycles). This part of our cycle is termed the late luteal phase. Our energy levels are influenced by a number of factors, including the role that estrogen and progesterone play in our brain, muscle protein synthesis and recovery. Furthermore, a common premenstrual symptom is disruption to sleep, which is integral to recovery, coordination, concentration and mood!

A simple way to make the most of the rest of our cycle is to schedule a deload week during the late luteal phase (commonly referred to as PMS) or potentially overlapping from the late luteal into menstruation. By scheduling a deload week during the time in our cycle where we may feel less motivated and lower in energy, we kill two birds with one stone. We make it easier to be more flexible when arranging our training week, as we simply have fewer sessions to fit in, so if we feel low motivation or tired one day we can simply push a planned session to another day. Having fewer sessions means we have more energy for the ones we do do, and therefore, are likely more motivated for them. Although consistency in exercises is key to making adaptations, maintaining motivation and not dreading having to do certain sessions will help with consistency and sticking with training in the long term.

A few simple things that we can do during this deload week are:

- Reduce the overall volume of training to allow more rest.

- Use lower intensity climbing sessions to focus on movement efficiency or being playful with sequences.

- Focus on stability or good form in conditioning exercises rather than pushing the weights and intensity.

- If completing higher intensity sessions, cut them in half (there is nothing to say you can't complete high intensity training or climbing during deload weeks, but keep the sessions short and fewer). This is where you can be selective about which higher intensity sessions you maintain during a deload week. You might choose those that are more important for your goals, or those you enjoy most!

- Be aware of fueling with carbohydrates before higher intensity sessions and of overall protein intake (this is actually good advice for any climber, but could be particularly useful during the luteal phase).

A deload week doesn't mean dropping everything and depending on what we find it easier to motivate for we could either maintain some structured conditioning and keep our climbing unstructured or maintain fewer structured climbing sessions and drop conditioning to solely stretching or mobility.

"I get cramps that make me feel like I don't want to climb"

Cramps are one of the most common symptoms associated with periods. They can range from uncomfortable to incredibly painful, and unsurprisingly they can make us feel like we don't want to exercise. Cramps can also be more pronounced during puberty when our menstrual cycles are just getting going - I can still remember the streams of girls at school lined up at the side of P.E. lessons due to bad period cramps. Does this mean that period cramps prevent us from doing exercise? The blunt answer to this one is "no", but this needs to be administered with a dose of subtlety and compassion.

- Keep moving, but make it gentle. If you suffer from bad cramps, it has been shown that movement helps to ease the pain (whether this is due to some physiological mechanism, or simple distraction I can't be sure, but ultimately it probably doesn't matter). Although cramps might make the prospect of throwing ourselves at the Moonboard unattractive, this doesn't mean we can't use climbing movement to ease the discomfort. As we have seen above, we can sync this phase when we experience cramps with a rest week, and so use easy mileage or low-angled climbing as a form of gentle movement. To give intention to these sessions we might want to experiment with mindful movement and coordinating movement with breathing, or relaxing our grip and finding well-balanced positions.

- Reduce load on the lower back and abdomen. We often use exercises in training that involve wearing a harness and attaching weight to it, and this might feel like adding insult to injury when we have cramps. Depending on how many days cramps are experienced for, this could simply be a matter of being flexible with our weeks and scheduling our max hangs for Saturday instead of Monday. Another option is to drop the weights during this week and focus on form in conditioning exercises. For example, if I am working on weighted pull ups I may schedule my rest week when I have my period due to the cramps I experience, and complete the same exercise but only at bodyweight, focusing on good scapula engagement and smooth movement throughout the pull up. The following week my next 3 week block of training will start and I will be back to adding weight when the cramps are long gone.

- Use supplements to ease the symptoms. In the 7 days leading up to your period you can start to pre-empt the cramps. We often think about taking pain relief during our periods - sort of like putting a plaster over a cut. This approach is more like taking measures to reduce the chance of tripping over and cutting yourself. Magnesium, Zinc, and Omega-3 fatty acids may help reduce cramping if taken in the lead up to your period. This may be a particularly useful approach to try out for elite climbers who have a competition schedule that can't be synced with their menstrual cycle. Although they might be able to adjust training, a big consideration will be how to mitigate symptoms if a competition falls on a day when they have cramps.

- Use pain relief. This may seem so obvious that it is barely worth including, but the "I don't need it"/"It's not that bad"/"If it doesn't go away in an hour I will take some" attitude towards pain relief is widespread, and period cramps are no exception. With the information from tracking, you can know when they are likely to come on, and be ready with aspirin. Using this form of anti-inflammatory could be more impactful due to the mechanism of effect on prostaglandins. If your cramps are bad, be prepared and take them from the onset. Again, being prepared in this way could be particularly useful for competition climbers.

Join the Lattice Women's Training Facebook group, where you can ask questions and discuss issues relating to training, the menstrual cycle and all related topics!