In a book on mountains of the world, John Cleare wrote (in a fittingly small section about British mountains) ,“In terms of size alone the mountains of Britain are insignificant. In terms of world mountaineering, however, their influence has been tremendous and although they offer superlative rock climbing...it is as a crucible of men and ideas, of techniques and equipment, that the British mountains are remarkable”. So what forces begat the men (and women) who inhabit this 'remarkable' climbing microcosm? One could speculate that Britain's small-scale geography yet large-scale influence on the climbing world – its varied geology and idiosyncratic climbing personalities - are somehow connected. That, aeons ago, a cataclysmic earthquake occurred (whose epicentre was somewhere near present-day Sheffield). It was as if the circumscribed geology of the British Isles could no longer contain the primal energy of emerging biological life, and a metamorphosis of man and rock occurred; followed by a tumultuous twisting and folding; resulting in a distorted mutant race who love to climb rocks, drink beer and to blather on internet climbing forums about their Favourite Biscuits.

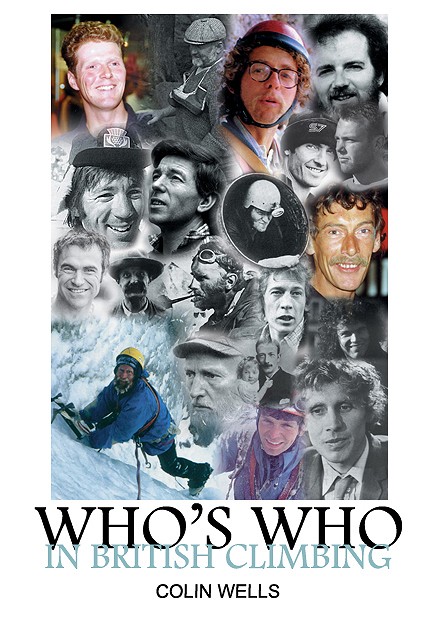

Colin Wells' book is less about why British climbers are different than the Who Are We? issue, but it does share the premise that there is something peculiar (in both senses of the word) about British climbers. He attempts to catalogue this curious species (Homo Gritannicus?) - “the romantics, eccentrics and buffoons who have made British climbing what it is”. Indeed the very idea of compiling a compendium of eminent British climbers past and present seems ideally suited to someone from the nation that invented butterfly-collecting and trainspotting. Produced by the Climb magazine team, it's a big book; the size of a small bouldering mat; ideal for shorties to stand on to reach the starting holds of a climb. Nearly 700 mini-biographies are arranged alphabetically in 575 photo-peppered pages - an exercise in taxonomic monomania that Colin – or maybe it should be H.G. 'Hard Graft'? - Wells has obviously conducted in a spirit of pith-helmeted enthusiasm/delirium. No character-type avoids his scrutiny. So, as well as the romantics, we have the rogues, rakes, ruffians, reivers, rebels, radicals, reactionaries, the risible, repellent and ridiculous. One is reminded of that quintessentially English classic, The Wind in the Willows, with its fascinating bestiary: jovial Mole (Chris Bonington?), conceited Toad (Ken Wilson?), wise Badger (Hamish MacInnes?), and nasty Weasels (Aleister Crowley?) and sneaky Stoats (Pete Livesey?) from the Wild Wood (home of the sport-climbing French and way-honed Yankee dudes, as well as the criminal contingent of Pof-users and chippers?).

Pursuing this bestial theme, the author's role model in collating this book's contents could well have been the Hedgehog – snuffling away in the undergrowth, gathering facts and quotes, to take back to his burrow (somewhere in Hope). As Reviews Editor for Climb magazine, he displays the prickly wariness that reviewers turned author are wont to display (Please don't be nasty to my book!) – e.g. the Frontispiece quote begs the reader to refrain from carping criticism and to be indulgent, the Acknowledgements blames the 'lousy idea' for the book on Gill Kent and Neil Pearsons, and the Introduction lists all those categories of reader who won't like it – i.e. everyone in it, everyone not in it, bearded men in cardigans who attend mountain literature festivals, and people who post on internet forums! As someone not in the book (my omission presumably attributable to being a half-Cypriot born in Germany – how else to account for the shameful neglect of my major contributions to British climbing at Lumbutts Quarry?) and an internet poster, but not a cardigan-wearer or beard-possessor, there was presumably an equal chance I might like or not like it...

Each climber's name is presented in alphabetical order – accompanied by a sometimes less than HD-quality photo - subtitled with a pithy pun, aphoristic appellation or wacky wordplay; then followed by a mini-biography, and concluding with a 'What they said', 'What s/he said' quotation (and, in some cases, a list of Standout Climbs and suggestions for Further Reading). Having digested the book in several sittings and using a variety of reading styles, I feel that whether one likes or dislikes this book will depend primarily on one's expectations – if expecting some definitive historical reference work to be taken off the shelf whenever seeking some fact or detail, then, as the author openly admits, this is not the book for you.

The book makes no great claim to scientific objectivity, preferring instead a ramshackle approach. And yet, the temptation to try to be all-encompassing sometimes gets the better of the author, resulting in the less than satisfactory 'composite' or 'lump 'em all together' sections' (e.g. the Generation X and Y sections dealing with younger climbers) where an extension of the Kill Two Birds With One Stone principle (Kill Twenty Climbers with One Rock As Quickly as Possible?) has been enlisted. However, if one isn't a pedantic Mastermind entrant, most casual readers dipping into the pages at random will uncover some quirky hitherto unheard-of pioneer, eccentric, feminist or madman from the 'Golden Age' of British climbing who sounds engaging enough for the reader to delve into further. Another factor may well be the reader's level of knowledge. In a curious way, the 'well-polished' content dealing with climbers from the 1950s to the 1990s makes for less gripping reading because many of the quotes and stories will be familiar to many of us. That said, it is good to have many of these 'classic' anecdotes and quotations all together in one place for the first time. Younger readers will no longer have an excuse for approaching Ron Fawcett at the crag and enquiring 'Are you J.W. Puttrell?' Stylistically, the book treats its characters as condensed caricatures – a sort of Horrible Histories approach – that 'serious' readers will baulk at. And the tone adopted is 'racy' and 'breezy' - a humorous, ribald, flippant 'voice' that may irritate if reading from cover to cover, but is often amusing in smaller doses. The font size is small and makes quite a demand on my Allan Austin-quality eyesight and there are quite a few typos and spelling mistakes that would have benefited from a more searching proof-reading (head torches essential for proof-readers?), but these are minor quibbles.

In summary, what we have is a good old-fashioned Boys' Bumper Book of British Climbing (very much a British tradition of my youth) that one could happily sit down with and guffaw away a rain-affected afternoon in a hut in Snowdonia or a dark winter's evening in a Highland bothy. An ideal present for Christmas? Well, in these Credit Crunch times, £20 may seem a bit steep for many of us. But, if Kevin Jorgeson and Alex Honnold are looking for a memento to take back to the USA to remind them of their visit to Britain, they would no doubt find it an edifying, if mystifying, read. As I said, sometimes outsiders help show us who we are, whilst remaining oblivious themselves to the multiple mythic layers of history, culture and psychogeography we British climbers metaphorically climb upon every time we head up to Stanage or dream of Everest.

Example Entry.

Geraldine Taylor (1954-)

The incredible shrinking woman

For a time in the mid-'80s, Geraldine Taylor was probably as famous for losing three stone, as for being one of the leading British women rock climbers. After years of being hauled around as a semi-portable 11 stone 5lb belay (by, amongst other celebrities, an exhausted Mick Fowler»), she woke up one morning, probably screamed something like 'I am a winner', and embarked on a Nietschean Will-To-Power four month transformation into a lithe, nimble 8 stone 4lb Rock Goddess. Why anybody was bothering with Jane Fonda's best-selling workout video of the time and not following the simple GT direct route to sylph-like status is probably answered by the fact that she restricted herself to a sphincter-shrinking 1000 calories a day. 'It was a bit crazy really – I was still eating junk. Some days I'd have a buttered scone, and that was that for the day.' Whatever, the results were startling: she shot from mild Extreme bumbly, to honed E5 crimp 'n' crank mistress. The new pre-shrunk body was also partly one of the reasons behind the trend towards the notorious climbing fashion crime of the mid- '80s: silly climbing tights. With her new found image confidence Taylor became famous for sporting a daft wardrobe of glam silk and lycra tights. It was only a matter of time before hairy-arsed blokes started copying the example to a distasteful degree – and the rest is embarrassing history..

Who's Who in British Climbing by Colin Wells contains nearly 700 mini-biographies of climbers – the romantics, eccentrics and buffoons that have made British climbing what it is: dissolute and hungover most of the time, with the odd unexpected burst of brilliance. They form a world-class cast of eccentrics ranging from the most virtuous to the most hedonistically barbarous characters one could ever hope to meet.

ISBN 13: 9780955660108

No of Pages: 576

Page Size: 146 x 210

Publisher: The Climbing Company*

Published Date: October 2008

Cover: paperback

Illustrations: b/w photos

Price: £20.00

Comments